“An Account of What I Here Am Silent About” — A Week of Bibliomancy, Day 4

A seven-day divinatory reading experiment

Dear Living Dark reader,

It’s Day Four of my (our) week-long experiment in bookish divination. You can catch up on the whole series if you like, or just dive in right here.

But first, in case you wondered, my friend Wikipedia says, “Bibliomancy is the use of books in divination. The use of sacred books (especially specific words and verses) for ‘magical medicine’, for removing negative entities, or for divination is widespread in many religions of the world.”

As on the previous days, today’s passage was given to me through the agency of my blindly reaching hand while I stood before the bookshelf in my college office with closed eyes and deliberately defocused attention, letting the hand touch whatever book mutually reached out to it first. It also involved the agency of my left index finger when it landed “randomly” on the page that had opened itself up with equal “randomness.” And that passage is this:

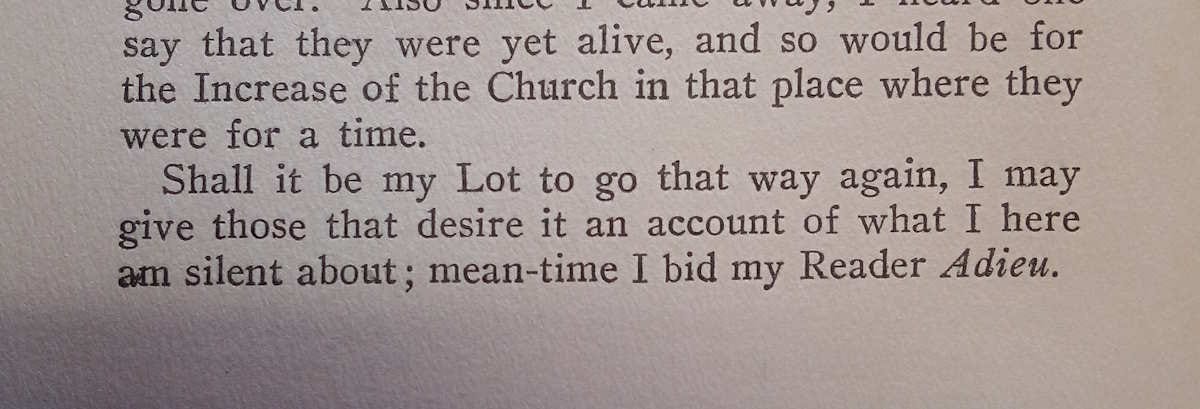

Shall it be my Lot to go that way again, I may give those that desire it an account of what I here am silent about; mean-time I bid my Reader Adieu.

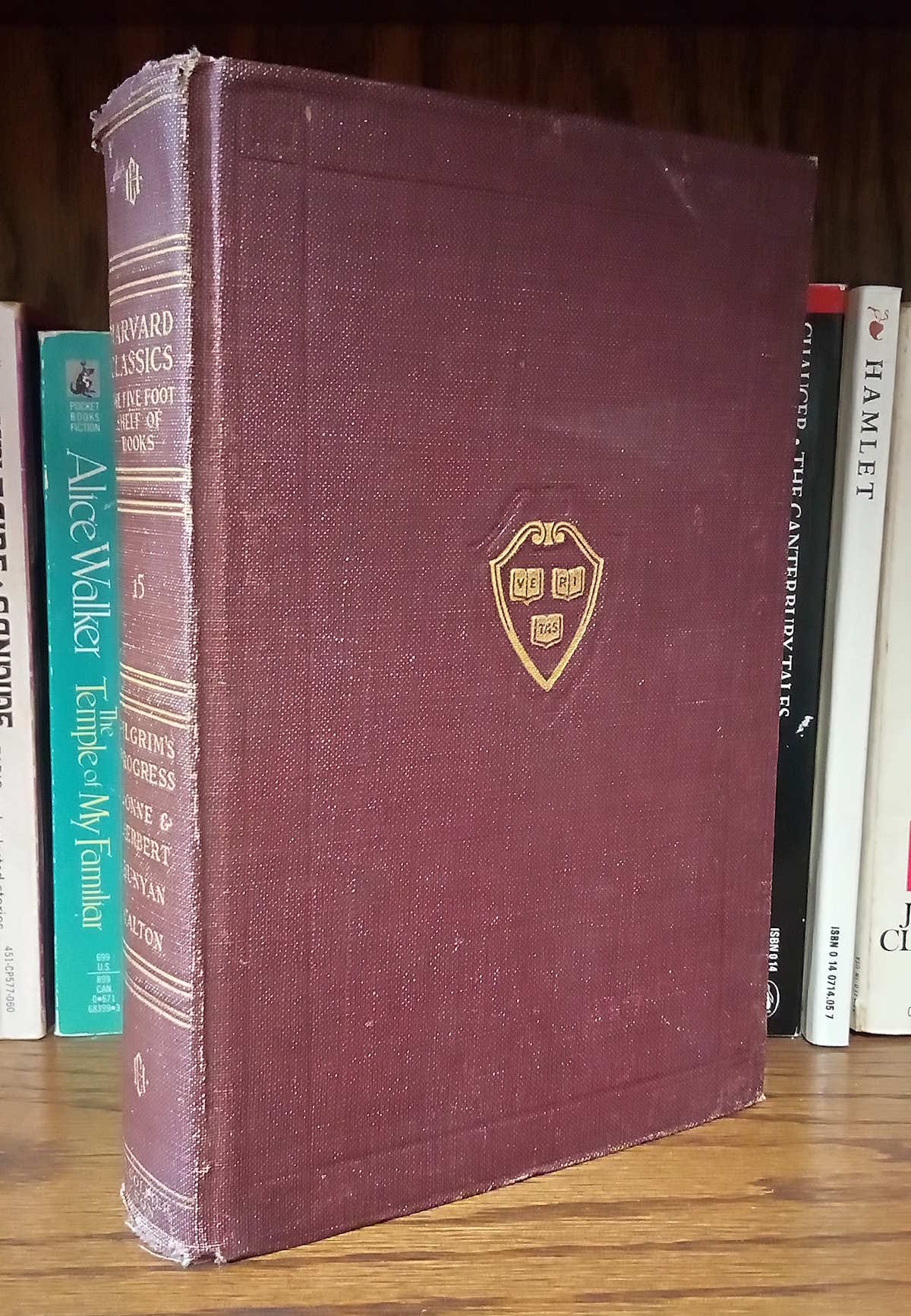

It comes from John Bunyan’s classic seventeenth-century allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress, as appearing in volume 15 of the 1909 Harvard Classics edition, which contains both The Pilgrim’s Progress and Izaak Walton’s Lives of Donne and Herbert.

As I go about seeking to intuit the significance or resonance of these words both in and for today’s specific context, I think I have to start by noting their placement in the book: they are its closing lines. They’re the final words the unnamed narrator—generally assumed to stand for Bunyan himself—speaks to the reader. Surely this is not unimportant.

Nor is it unimportant, in connection with Day One’s delivery of key lines from Puck’s closing apology to the audience in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, that The Pilgrim’s Progress is explicitly presented by Bunyan as representing a dream. Its opening line, after the author’s introductory “apology” (justification or explanation), is: “As I walked through the wilderness of this world, I lighted on a certain place where was a Den, and I laid me down in that place to sleep: and, as I slept, I dreamed a dream.” The entirety of what follows is then framed as Bunyan’s allegorical dream of a man named Christian and his encounters with temptations and obstacles as he journeys from the City of Destruction (earth) to the Celestial City (heaven).

Even more: The Pilgrim’s Progress consists of two parts. The first was published in 1678, the second six years later, in 1684. Part One not only begins with an announcement of its dream origin but ends with further reflections on it. After telling how Christian and his companion Hopeful finally reached the Celestial City, Bunyan closes with: “Then I saw that there was a way to hell, even from the gates of heaven, as well as from the City of Destruction. So I awoke, and behold it was a dream.” He follows this with a concluding poem that rounds off the book’s opening apology. It is only twenty-three lines long, and it begins:

Now, Reader, I have told my dream to thee;

See if thou canst interpret it to me,

Or to thyself, or neighbour; but take heed

Of misinterpreting; for that, instead

Of doing good, will but thyself abuse:

By misinterpreting, evil ensues. In the remaining lines of the conclusion, he urges the reader to look past the story’s surface charm to uncover its deeper meaning

The resonance and contrast with the words of Shakespeare’s Puck is striking. Whereas Puck urges the audience to consider the play they have watched as a mere dream if anything in it has offended them, since they can then just dismiss it all as airy fantasy, Bunyan invites his readers to interpret the dream of the pilgrim’s progress carefully, seeking to uncover its essential truth.

And then there’s the striking significance of from Book Two again, as presented to me today: “Shall it be my Lot to go that way again, I may give those that desire it an account of what I here am silent about.” So, then . . . there are things Bunyan didn’t put in the book, things he was “silent about,” that would reveal still deeper or other meanings? This explicitly “meta” closing to one of Christianity’s greatest works of literature, with its reflection on the simultaneous revealing and concealing nature of relating, of narrative storytelling—recall the dictionary definition of “relation” that offered itself up yesterday—has obvious interlaced resonances with the question of revealing and obscuring truth, and of truth’s social construction, in The Crucible, as I briefly reflected on yesterday.

A full disclosure like the one I made when Miller’s play came up two days ago: I have never read The Pilgrim’s Progress straight through. Oh, I’ve read parts of it, of course. I know its general origin, meaning, story, theme, and cultural significance fairly well. I recall it first entered my awareness during my early teens when I attended church camp—something I did for several summers in my youth—and the camp counselors screened a low-budget, live-action movie adaptation of it for the assembled campers one evening. Our collective response was one of mingled confusion and semi-subdued hilarity. I particularly remember a burst of laughter when Christian begins sinking in a bog or marsh and cries out, “Help! Help!” And on cue, a man shows up and pulls him out, announcing, “My name is Help. I heard you calling.” Suffice it to say that the rhetorical posture of seventeenth-century Christian religious allegory did not land well with with the sensibilities of 1980s Missouri adolescents.

I think that’s all for today. I’ll be back tomorrow for Day Five. Right now, I’m looking forward to seeing what you’d like to share from your own bibliomantic gleaning for today, if you’re playing along.

Warm regards,

The Kindle edition of Writing at the Wellspring is available for preorder. Much of its content was first published here at The Living Dark in a different form. Whether you’ve known my work for years or are just coming across it, this book brings together my thinking about creativity, inner silence, the daemon muse, and the strange, life-shaping currents beneath inspiration. It’s part craft, part philosophy, and part spiritual manifesto.

If this resonates, know that preorders genuinely help a new book reach the readers who might need it. December 15 is the release date for both print and electronic editions.

“[An] intimate journey into the mystery of creativity and spirit… Cardin weaves practical methods, personal stories, literary references, and mystical insights into a lyrical meditation on what it means to create from the depths of the soul… both deeply personal and universally resonant.” — BookLife review (Publishers Weekly)

“A guide for writers who welcome the dark and hunger for meaning.

— Joanna Penn“I can’t think of any [other books] that link the creative act so uniquely or persuasively with spirituality.”

— Victoria Nelson“A meditation on the silence and darkness out of which all creative acts emerge....A guide for writers unlike any other.”

— J. F. Martel“Important to any writer ready to see through the self illusion and realize the freedom this brings to any creative work.”

— Katrijn van Oudheusden

Matt, I have been enjoying this series so very much.

I first encountered the Pilgrim’s Promise through another book that had a profound impact on my childhood and shaped many of my ideas about what it means to live a virtuous life. In Little Women, The Pilgrim’s Progress serves as the foundational religious allegory. Their struggles hearken back to that spiritual journey over and over again. Amy’s “Valley of Humiliation,” Jo’s battle with “Apollyon” (her temper), as they strive toward self-improvement and womanhood. I have always identified with Jo March in so many ways, and I still do. The theme of this journey of personal growth continues to shine through in this exercise.

My day 4:

“It didn’t look like the Lonely One at all”, gasped Charlie. “It looked like a man.”

“Right, yes sir, a plain everyday man, who wouldn’t pull the wings off so much as even a fly, Charlie, a fly! The least the Lonely One would do if he was the Lonely One is look like the Lonely One, right?”

Dandelion Wine by Ray Bradbury pg. 178

Dandelion Wine is my all-time favorite novel. I have read it countless times. To me it seems to be almost poetry, filled with brilliant nostalgia and deep meaning.

Over the years, I have thought about the name of this fear embodied in the Lonely One. I remember as a child having similar fears. In adulthood, it turns out that the most destructive elements that enter life do not look like ferocious beasts or evil incarnate. Many times they are just hurt people, who then hurt others. Destruction is a lonely place. And while I try to avoid it, I have sympathy for those who are in that space. The antithesis of connection is operating in that selfish alone way.