Art as Trap and Transcendence

An autobiographical meditation on creativity and disillusionment

Dear Living Dark reader,

What is the relationship between art and the rest of our lives? Does art enhance our experiences and relationships? Does it complement them? Enrich them? Illuminate them?

Or it is just the opposite? Do art and life stand in conflict? Does each injure the other, steal from the other, sap the essence of the other? If we feel called to appreciate a certain kind of art, whether writing or music or painting; and if we feel called not only to appreciate it but to practice it, to engage in its creation; and if we assent to this call; and still further, if we actively devote ourselves to this art, investing untold amounts of time in it, maybe even committing the better part of our lives to carving out our home within its mutual embrace—if we do this, are we in fact depriving ourselves and those who ostensibly count as our “loved ones” of the real essence of who we are and what we have to offer?

To put it differently: Is art a vampire? Does it drain meaning and vitality from the rest of our lives to give us the temporary bliss of inhabiting a beautiful otherworld that is inevitably revealed in the end as false and hollow? Is the lure of art a siren song that we willfully misrepresent to ourselves as the road to meaning, the call of the divine, the highest voice we can answer?

Welcome to a well-developed wing of my mind, built on a lifelong vein of tension running through and beneath my inmost affections.

The seeds of this suspicion about art were planted in me early in life by the fact that I was an intellectually and affectively high-strung youth with a voracious love of books, movies, and music, a natural verbal, musical, and literary talent, an innate interest in questions of religion, philosophy, and life meaning, and an inclination and sensibility that, by the time I graduated from high school, and with help from nominally positive feedback in my interpersonal environment, had shaped itself into a self-conscious allegiance to all of the above. I can see in retrospect that this combination of traits, talents, and predilections provided the perfect staging ground for a blowout. Emotional intensity plus creative/intellectual precocity plus external reinforcement equals a lit fuse in the self-obsessed psyche.

Is art a vampire? Does it drain meaning and vitality from the rest of our lives to give us the temporary bliss of inhabiting a beautiful otherworld that is inevitably revealed in the end as false and hollow?

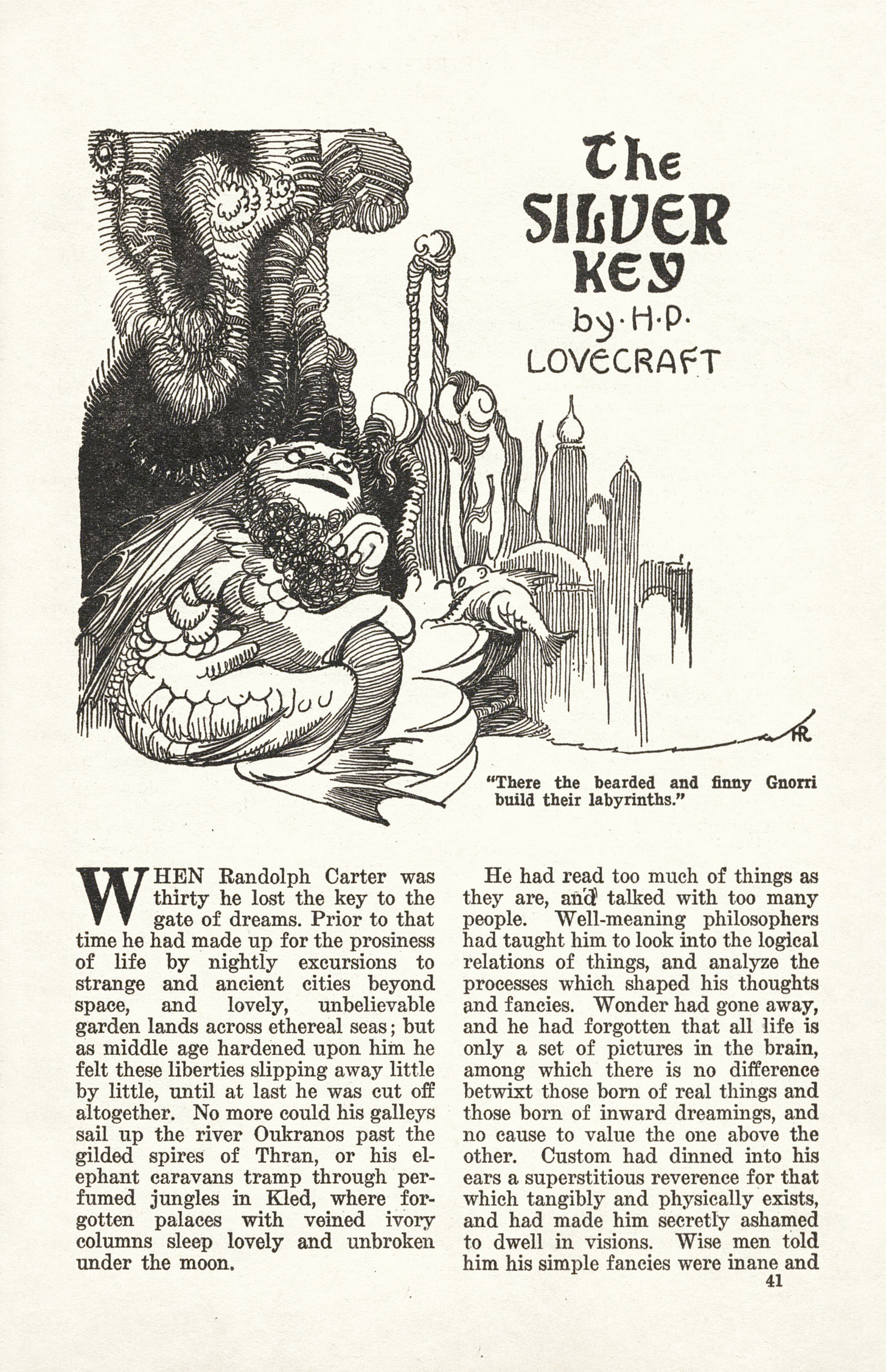

It was in college that the lurking danger of this orientation first revealed itself. This occurred in connection with the academic, creative, and interpersonal experiences that became newly available to me at the University of Missouri, where not only my formal studies in communication, electronic media production, and philosophy, but my extracurricular plunge into the works and secondary materials surrounding the likes of H. P. Lovecraft, affected me in ways that are still revealing themselves.

Lovecraft, for example, was an atheist and philosophical materialist who was transported to heights of emotional and aesthetic rapture by art, literature, and scenes of natural beauty, even as his principles told him these things, including his subjective reactions, were really just the mechanistic manifestations of a blind universe that was eternally grinding its way from nothing to something and then back again.

In his story “The Silver Key”—which, to employ a literary generic term that did not exist in Lovecraft’s day, might be accurately characterized as a fantastic autofiction—he gave narrative voice to this aching tension in his life by telling of the agonized disillusionment of his literary alter ego, Randolph Carter (a recurring character in his stories), who had been drawn to myths, dreams, and beauty from childhood, but who found these all painfully undermined by modern science and societal philistinism as he reached the age of maturity:

When Randolph Carter was thirty he lost the key of the gate of dreams. Prior to that time he had made up for the prosiness of life by nightly excursions to strange and ancient cities beyond space, and lovely, unbelievable garden lands across ethereal seas; but as middle age hardened upon him he felt these liberties slipping away little by little, until at last he was cut off altogether....

He had read much of things as they are, and talked with too many people. Well-meaning philosophers had taught him to look into the logical relations of things, and analyse the processes which shaped his thoughts and fancies. Wonder had gone away, and he had forgotten that all life is only a set of pictures in the brain, among which there is no difference betwixt those born of real things and those born of inward dreamings, and no cause to value the one above the other....

They had chained him down to things that are, and had then explained the workings of those things till mystery had gone out of the world....

Having perceived at last the hollowness and futility of real things, Carter spent his days in retirement, and in wistful disjointed memories of his dream-filled youth.

Eighteen-year-old me first read these things while lying on his bed in a seventh-floor dorm room in Columbia, Missouri, and savoring the enhanced pleasure that always attends time stolen from formal obligations to indulge in private pleasures. But amid the enjoyment, my sense of pleasure at HPL’s sensitive description of Carter’s inner dilemma was mingled with sadness, because, to my surprise, I identified with it. It struck close to home. Right there in late adolescence, I intuited that my childhood ability to lose myself in worlds of imagination and ideas would grow progressively dim as the “real world” of the mundane, the world of jobs and material obligations with its attendant practical and mundane outlook, rose to claim me. As I lay there on my bed reading, that world loomed ominously on the far edge of college and the threshold of societally identified adulthood. For some reason, I was wired to view that world as a realm of utter disenchantment, a place where art, spirit, and intellectual enjoyment went to die.

During my freshman year, I encountered Friedrich Nietzsche for the first time by way of his The Birth of Tragedy, which I was assigned to read in a humanities class taught by Dr. Doug Hunt, whose editorship of The Dolphin Reader, a widely used literature anthology in undergraduate English courses, acted synergistically with his winning personality—soft-spoken, affable, approachable—and his impressive erudition to make him one of my favorite professors. Under his tutelage, I discovered a philosopher who wielded the power to cast a spell over me with his words:

In this sense Dionysian man might be said to resemble Hamlet: both have looked deeply into the true nature of things, they have gained knowledge and are now loath to act. They realize that no action of theirs can work any change in the eternal condition of things, and they regard the imputation as ludicrous or debasing that they should set right the time which is out of joint. Knowledge kills action, for in order to act we require the veil of illusion; such is Hamlet’s doctrine, not to be confounded with the cheap wisdom of Jack the Dreamer, who through too much reflection, as it were a surplus of possibilities, never arrives at action. What, both in the case of Hamlet and of Dionysian man, overbalances any motive leading to action, is not reflection but knowledge, the apprehension of truth and its terror. Now no comfort any longer avails, desire reaches beyond the transcendental world, beyond the gods themselves, and existence, together with its glittering reflection in the gods and an immortal Beyond, is denied. The truth once seen, man is aware everywhere of the ghastly absurdity of existence, comprehends the symbolism of Ophelia's fate and the wisdom of the wood sprite Silenus: nausea invades him.

This gloomy characterization of true sight, the true penetration of reality, as something that leads to paralysis because of its sheer terror sank its hooks into my soul. I could not stop thinking about it. And I found its fascination to be long-lasting, extending well beyond that first reading, extending in fact to my life beyond college. It was something I returned to many times later in my twenties to reread, ponder, and lament as I was trying to find my place in the world. Sometimes you encounter an idea at precisely the right moment for it to invade and inflect your perception of everything. That’s what Nietzsche did in The Birth of Tragedy, especially since his larger overarching point about art’s redeeming and exalting power only increased my gloom, particularly in connection with his vivid interpretation, borrowed from Schilling, of the chorus in Greek drama as a wall erected to protect the sacred world of art from the profane and prosaic world of the everyday. This notion and vision lodged in my mind and would not go away: that the art and ideas I loved, and the realm of spirit to which they pointed and in which they subsisted, were really just airy realms of abstraction, empty visions walled off from the real world and standing in essence as cruel traps for the mind and soul because they could not fulfill, because only reality can fulfill, and because the reality to which they stand in winsome but deceptive contrast is nothing but a galling grind in exactly the way Lovecraft/Randolph Carter had known it to be.

Though full awareness of it didn’t come clear until later, right then, at age eighteen, I began to have the first intimation that I was doomed, as it were, to feel helplessly, inexorably driven to indulge in false visions that called to me with the perfume of paradise, promising a life of enlightened pleasure and transcendence, but that revealed themselves in the end—and not only in the end but all along, in real time, for one who has eyes to see—as hollow illusions.

At least that was how my undergraduate self saw it, when he thought about it, which he couldn’t help doing with the same obsessiveness that he brought to most things.

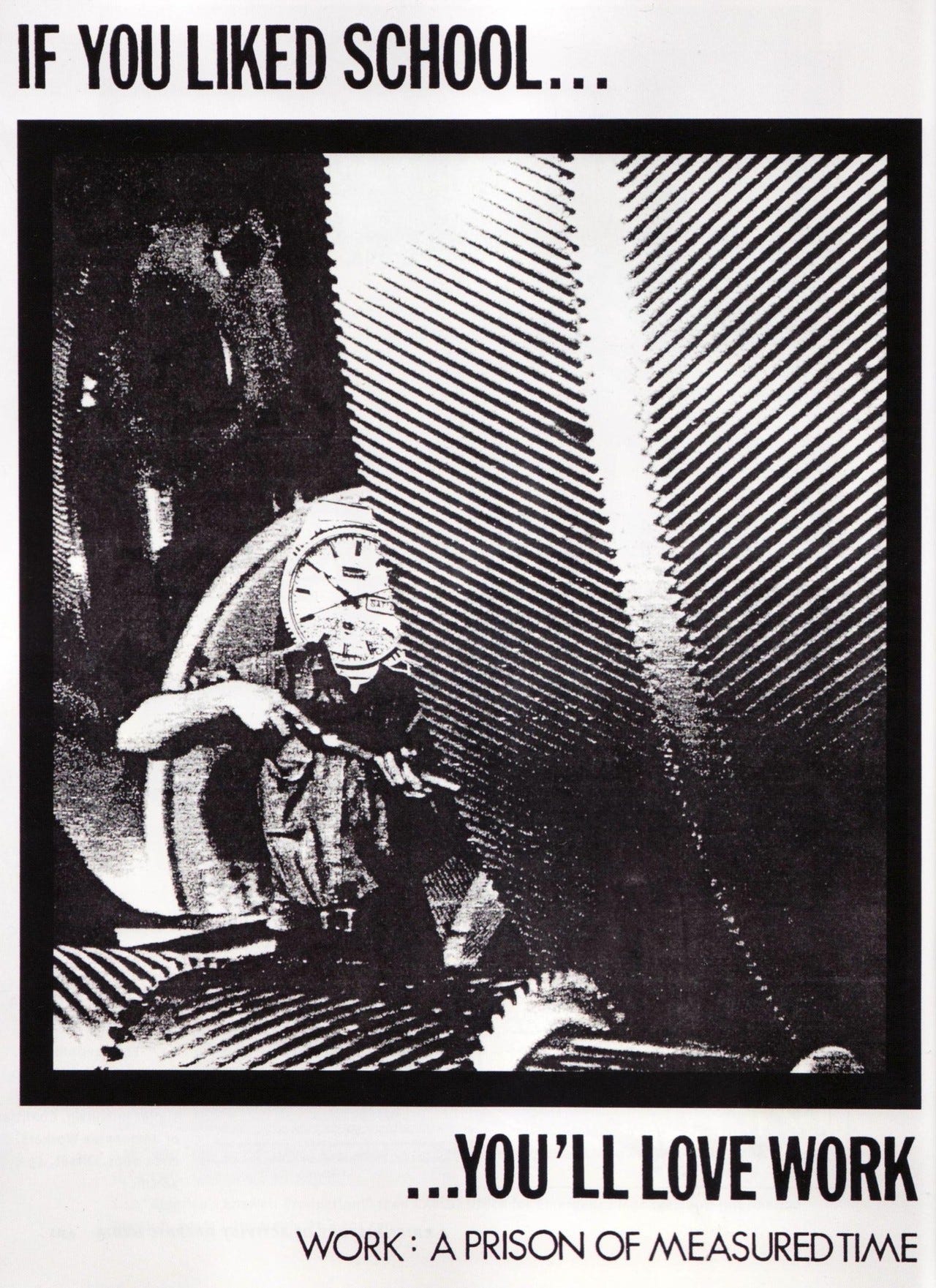

After three years of college life, as graduation and matriculation into The Real World began to assume the status of an actual event bearing down on me instead of a future fiction that would never arrive, I discovered that I had unwittingly engineered a crisis. My freshman glimpse of a corrosive despair revealed itself to be not an acute sickness but a chronic one. The world of art and ideas that I had chosen to inhabit, and that I had too preciously spent a great deal of time and energy representing to myself and others as Very Important, seemed ever more empty and impotent in the face of having to figure out how I was going to earn a living. Sure, I had already had several jobs. I had worked for money. I had experienced the world of gainful employment and material necessity. And I had pretty much loathed it. Now I was on the precipice of the final, unavoidable, irrevocable step that would tip me over into a new phase of life that I had enjoyed denying for years. “What are you going to do with your life? How will you get a job?” The very questions felt like they were inserted into my consciousness by a monstrous alien source. That source was the aforementioned Real World. Reality itself was a trap. I wanted to write, and to make movies and music. Sure, you could do that in the Real World. But at what cost to your integrity? And—in light of the awful emptiness of art and ideas that I had been alternately grappling with, denying, lamenting, and grimly accepting—what for?

During the fall semester of my senior year, I took a course in interpersonal communication that was taught by a professor who had become special to me, someone whom I had come to view as a philosophical mentor. Unexpectedly, in his class I found myself confronted with a quintessential articulation of my private despair. It happened around the middle of the semester, when he screened the movie My Dinner with Andre for the class and asked us to write a brief paper in which we discussed the tempo and methods of self-disclosure that Wally and Andre each displayed in their conversation. Today I’m convinced that his real purpose was simply to find an excuse to introduce us to that movie, which remains one of my favorites to this day.

The world of ideas and art that I had chosen to inhabit, and that I had too preciously spent a great deal of time and energy representing to myself and others as Very Important, seemed ever more empty and impotent in the face of my having to figure out how I was going to earn a living.

Among the many things about My Dinner with Andre that mesmerized me were the following lines by Wally, the movie’s fictionalized version of the real-life Wallace Shawn, who delivers them as voice-over narration during the opening scene in which he navigates the New York City subway system and the streets of Manhattan on the way to meet his old friend Andre Gregory for dinner at a fancy French restaurant:

The reason I was meeting Andre was that an acquaintance of mine, George Grassfield, had called me and just insisted that I had to see him. Apparently, George had been walking his dog in an odd section of town the night before, and he’d suddenly come upon Andre leaning against a crumbling old building and sobbing. Andre had explained to George that he’d just been watching the Ingmar Bergman movie Autumn Sonata about twenty-five blocks away, and he’d been seized by a fit of ungovernable crying when the character played by Ingrid Bergman had said, “I could always live in my art, but never in my life.”

As you may imagine in light of all the above, this struck me as a college senior, and continues to strike me now, as almost unbearably poignant.

Some years later, I discovered that Wally, or else his friend George Grassfield, had not quoted from Autumn Sonata verbatim but had paraphrased it. The actual lines spoken by Charlotte (Ingrid Bergman’s character), or at least one English rendering of them, are as follows, and they reverberate all the more deeply because they are spoken by a person who is in process of being confronted late in life with the consequences of having sacrificed human love and connection for a career as an artist, in this case, a renowned concert pianist:

It was only through music that I could express my feelings. Sometimes, when I lie awake at night, I wonder whether I’ve lived at all.

It is not immaterial to observe that this view of art and life, and the inner human experience that it expresses, whether as paraphrased by Wally or as articulated and dramatized in Autumn Sonata, is made all the more poignant in My Dinner with Andre by the fact that it comes up moments after Wally has described, again in voice-over narration, what might be called his self-perceived “fall from grace” as he progressed from youth to adulthood:

I’ve lived in this city all my life. I grew up on the Upper East Side. And when I was ten years old, I was rich, I was an aristocrat. Riding around in taxis, surrounded by comfort. And all I thought about was art and music. Now I’m 36, and all I think about is money.

In recent years this dialogue has made its way into online meme culture, being passed around and shared by many people as an expression of the spiritual trap of contemporary consumer-capitalist society. Every time I come across someone sharing Wally’s words, whether textually or in a video clip, a little remembered flame of mingled delight and despair blooms within me, and I return to what feels like center, like ground zero of the innate emotional tone or tenor that, in combination with spiritual longing and numinous dread, has characterized the long arc of my life.

At this point maybe you, like me, are wondering about the reason for this spontaneous trip down disillusionment lane. Because that’s what this self-absorbed and strangely logicked essay is: spontaneous. I had no intention of writing about all this stuff, and no idea that I was going to do it. So, what was it that set me off on this meditation about my recurrent lifelong sense of unhappy indecision over art’s function as something that ennobles, enriches, and fulfills or something that lures and then undermines?

The proximate cause was a line from an actor and musician that I stumbled across recently in connection with the fact that my wife and I have been watching our way through all six seasons of Northern Exposure. I first watched this series intermittently during its final three seasons back in the 1990s. Presently, I am being reminded of what a genuinely brilliant show it was. And as is my wont whenever I’m going all-in on a television series, or a film genre, or a writer’s body of work, I have been reading up on it.

One of the supporting characters in Northern Exposure’s fictional world of Cicely, Alaska, is Walt the trapper, a gruff, gravel-voiced older man who lives in a cabin outside town, and who adds his own distinct element of charm to the show’s signature quirkiness. A few days ago, I found myself reading about Moultrie Patten, the actor who played Walt. I was intrigued to learn that Patten was not just an actor but a skilled jazz pianist, and also a former tank commander in World War II who had been awarded the Silver Star. Then I found myself reading, and then rereading, and then pausing to read yet again, a sentence that burst open the well of my memories and brought up all my conflicted feelings about art and life.

The line appears in Patten’s obituary, titled “Actor, Jazz Musician Moultrie Patten Dies in Beaverton,” which was published in Portland’s The Oregonian two days after his death in March 2009. After noting that Patten had been best known for his portrayal of Walt on Northern Exposure, and that he had died of pneumonia at age 89, the obituary says the following:

According to Patten’s daughter, Sarah Goforth of Portland, Patten often summed up his philosophy toward acting with this saying: “Anyone who pursues the arts is really creating another world for themselves, because the one they are faced with does not, in some way, suit them.”

I feel the need to repeat that line in italics, the better to pause and absorb it with you, because of its resonance with everything that I have been going on about here: “Anyone who pursues the arts is really creating another world for themselves, because the one they are faced with does not, in some way, suit them.”

All these years later, three decades after I suffered my youthful college crisis and managed to, after a fashion, get through it, there is still a version of me, call him Matt the Artist, that savors such words and wants to shout them from the rooftops. Yes, says Matt the Artist, that’s just how it is. The purpose of art is to redeem the world by showing us a higher version of it, to make good on our divine dissatisfaction by creating another world that is, in the end, more real than this one, and that reveals and constitutes the natural environment to which our souls rightly and continually aspire. C. S. Lewis had it right with his apologetic of longing: Sehnsucht, the aching, inconsolable longing for an infinite beauty, the very experience of which feels simultaneously joyful and tantalizing, points to something real. “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy,” Lewis famously argued, “the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.” The purpose of art is to seek, to see, and to channel this vision.

But another version of me, call him Matt the Disillusioned, receives such words, both Lewis’s and Patten’s, with a pang of melancholy and a surge of depressive emptiness. He reads Patten’s statement in a way that is ironically inverted from what the man surely intended. You say you want to create another world because you don’t like the one you see? Sorry, but all this does is trap you in a baseless hyperworld of empty emotion, elevating you for a few giddy moments into a space that feels like paradise, after which you realize you have no choice but to come crashing back to earth. Trying to escape the world as given, the world of the infinite meaningless grinding cosmos, not to mention the world of money and politics and the whole societal-material grind with its Gordian tangle of mostly arbitrary obligations, is an act of self-injury. It’s the doom of the Romantics, the fallacy of feeding on your own emotions, of deliberately heightening your affective sensibility, and maybe even your philosophic worldview, with false promises, and in so doing, burning out your soul.

Trying to escape the world as given, the world of the infinite meaningless grinding cosmos, is an act of self-injury. It’s the doom of the Romantics, the fallacy of feeding on your own emotions until you burn out your soul.

Matt the Disillusioned often recalls the famous lament—which he (Matt, I) first encountered in the same humanities class where he met Nietzsche—that Wordsworth poetically articulated regarding his inability to feel again as he had felt in his youth, to regain the sense of freshness and wonder that had been driven out by adulthood:

There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream,

The earth, and every common sight,

To me did seem

Apparelled in celestial light,

The glory and the freshness of a dream.

It is not now as it hath been of yore;—

Turn wheresoe'er I may,

By night or day.

The things which I have seen I now can see no more.

The Rainbow comes and goes,

And lovely is the Rose,

The Moon doth with delight

Look round her when the heavens are bare,

Waters on a starry night

Are beautiful and fair;

The sunshine is a glorious birth;

But yet I know, where'er I go,

That there hath past away a glory from the earth.Today when I revisit those lines, I feel their melancholic force all over again. And I think: Oh, come on, William. Of course you can’t feel the old thrill anymore. By your mid-thirties when you wrote that, you had spent decades burning up your emotions with Romantic surges of intensity for their own sake, reveling in visions of a poetically transfigured world that, no matter how lovely, is just an empty and doomed escape attempt. You would have been better off to forgo the poetic fireworks and acclimate yourself to life on the ground, which may be dreary, but at least it doesn’t disappoint when you accept it for what it is.

There is no real ending to this spontaneous essay that has decided to write itself. The best I can do is resort to that last refuge of the writer who has reached the end of the line, the tail of the transmission, and is groping and listening for what comes next. Which is to say, I will quote from myself.

The issue I’ve been describing has remained active within me for more than thirty years. Naturally, this is reflected in my personal journal, which I still feel strange and uncertain about having made public. Here is a brief steppingstone set of entries across a twenty-year span—with roots extending a decade earlier, but these are the ones I could locate most easily in the moment—where the matter erupted onto the pages of my private self-conversation. The first is one of the scores of story ideas that I recorded in my journals but never brought to fruition:

6/26/01

A story about the struggle between imaginative life and hard “real” reality. Imagination naturally tends toward “walled-off” existence, ultimate escape from the strictures and ennui of daily mundane reality, but imagination is also vapid and unreal. Creeping nihilism: a man unable to enjoy his own greatest pleasure because he recognizes its falsity. And he recognizes the same problem in all beauty, all thought—in short, in everything except brute physical reality. Fineness of thought and imagination good for nothing but recognizing the futility and uselessness of thought and imagination.

Some awful thing happens while this man is transported by some artistic rapture, and his sense of security is forever shattered by the awful realization that such rapture is no protection, and in fact only renders one more vulnerable to piercing horror. (Is there perhaps a final redemption in surrendering to despair?)

“By the time I reached the peak of my artistic powers, I had already fallen into a state of despair at their inability ever to achieve the thing that was their natural goal. The recognition of the contradiction implicit in all artistic endeavor grew on me slowly, over a span of years. It came at odd hours, often, paradoxically, on the heels of my greatest triumphs, when my sense of fulfillment was still glowing warmly in my chest and eyes. It felt like a subtle sapping of my joy, as if a leak had sprung in my bubble of happiness, or as if someone or something were siphoning away my very ability to delight in my accomplishments.”

2/21/02 Thursday 9:05 p.m.

Utter, inescapable despair at the thought that all art is nothing more than a sophisticated sentimentality, a refined expression of longing for worlds that can never be.

Monday, May 30, 2011 – 6:15 a.m.

The ultimate point of imaginative pursuits like the reading and writing of literature, the making and enjoyment of music, and the enjoyment of all art is to transport us more deeply into the now, into the heart of what’s real, life’s depth dimension, the realm of soul. But these can also be employed for escape and abstraction, attempts to seek fulfillment in unreality. The dividing line is so subtle. It can even turn from one side to the other within the same person, in an instant.

My thoughts turn to Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire and its depiction of Louis’s final philosophical-emotional resting point of hopelessness: Even art came to seem horrifically, intolerably productive of despair, for it stood in Louis’s eyes as a palpable expression of its own ultimate, lying uselessness, since it referred to no truer world and served merely to remind him of life’s shrieking nothingness, its utter, appalling meaninglessness.

This vision has been mythically attractive to me for so very long. But when I indulge it, and it starts to gain its own autonomous momentum and life within me, it poisons and corrodes my life from the root upward.

Monday, February 24, 2020

What comes over me is the sense, the thought, that even if I do end up producing a good story or whatever, so what? What would it even matter? I mean to me or to anyone else. How could it possibly have any significance? The finished product itself, the time and effort that went into creating it, my experience of writing it, the reactions of the people who would read it, my experience of knowing those responses, the impact the story might have on someone—is there anything really worthwhile in any of that? Isn’t there just as much reason not to do it as to do it?

These days, I tend to watch such thoughts and emotions—along with all other phenomena, both objective and subjective—play out like waves unfurling. I don’t invest my sense of identity in them like I once did. They are just the way this particular expression, this relative locus of the Absolute, is karmically destined to play out. Or rather, they are the playing out of it. Not incidentally, so is your response to them, whatever it may be. All phenomena are impersonal and inevitable.

So, is art trap or transcendence? Distraction or divine? Siren song or spirit song? The only accurate approximation of an answer in verbal language is surely that it is both and neither, just as you and I are both and neither—both these individual appearances and not these appearances at all. The whole anguished conflict plays out for a shadow, a phantom, a dream self within the real Identity.

There really is an ultimate fulfillment like Lewis maintained. It’s the fulfillment that I-as-Matt am wired to seek in both the creation and enjoyment of art and ideas, and that I suspect you are, too, since you have read this far into an essay like this one. But the fulfillment is not in those things. It is not in any “thing” at all. And yet they all point to it, for one who knows how to look, and especially for one who knows how to look at the looker.

As I said, there is no end to this.

Warm regards,

I can't thank you enough for this. I think of all those who draw hidden strength from a Beethoven symphony, a Cormac McCarthy novel, a Pink Floyd album or a narrative by Thomas Ligotti, and are then able time and time again to go back to their prosaic existence instead of surrendering to despair, even though to a cynical eye these and countless other artists have thrown away their lives. More than this, the concrete world in which we live and suffer is as much the product of musicians, poets and novelists as it is of scientists, teachers and engineers, it is first of all the indirect creation of the metaphysical artists who have shaped our ways of perceiving and living in it. The possibilities evoked in a fiction can have an unthinkable actual transformative power in our life and vision, making us perceive new horizons beyond the trap and vapid repetitions of daily realities. If nothing else, art can make "reality" more real, divesting it of the veil of false familiarity, opening our eyes to the disquieting ungroundedness of it all.

And the artist? I am convinced that in the moment of creation, when the muse takes over, what he or she experiences is no extinction or loss, but rather an alchemy, a transfiguration of life, and at privileged instants even an absorbing communion of infinite glory, might the poet at the same time be lamenting the passing of all glory and beauty from the world.

And the feelings, thoughts and experiences you share with us here and in your journals resonate so deeply with readers because you've "recollected them in tranquility" and couched them in artistic form. This endows them with an aura that strangely inspires the creative quest even when they are ostensibly undermining it in the most radical ways, thus realizing C.S. Lewis's words where he speaks of him who "... cries out for his lost youth of soul at the very moment in which he is being rejuvenated". Matt the Artist trumps Matt the Disillusioned.

Recurring angst around artistic practice is difficult, sometimes excruciating, in no small part because naming it and seeing it clearly can feel elusive, if not downright impossible. Our experiences are different, but I know what it's like to anxiously stab around in the dark in an attempt to make peace with the Art Process. It's confusing as all hell, and can be excruciating. Years ago, as a young jazz musician, I went through the gauntlet in my own way. I've come out the other side, and can attest that these slippery, inscrutable tensions and cycles DO have an end point. You've taken a chance on publishing an essay that just "wrote itself," so I'll bet you're in the process of coming to your own.

With that said, I'd offer a few things (impersonally and inevitably). This comment also wrote itself. Take what's useful, leave the rest. Delete away as you see fit. Things playing out.

There's no wall between your imagination and the material world; if there is, it's a figment of your imagination. If your inner nihilist's made a habit of tearing your imagination down, it should also do that here. Only, I bet it won't. If it's so insufferably rational, press it for information about this glaring contradiction.

The split between "art dreams" and "hard reality" is arbitrary, destructive, and optional. "Real life" will seem meaningless as long as you keep feeding this belief. That being said, nihilism plays its own key role in this scenario. This whole conceptual setup is probably protective for you. But you deserve better than living in a bunker in your own mind.

Shot through your essay is a panicked need to hedge against the worst (whatever that is). Your relationship with artistic process seems hobbled, if not paralyzed, by a stubborn, longstanding self-protective reflex. Rationally and pragmatically, cynicism provides a fine cover for panic and grief. (I'm sure that's no news to you.) A sizeable part of this artist's angst is likely rooted in your body, not your mind. I can't imagine these thoughts not being the direct product of wounding (i.e., sticks and stones can break our bones, but words do also hurt us).

Last but not least, this was one of only a few key insights that helped me find peace: Even and perhaps especially if it's the very last thing you want to do, make it a duty and mission to love your inner nihilist. With care and commitment. See what happens.

Be free.