“We Must Treasure the Dream Whatever the Terror” — A Week of Bibliomancy, Day 7

A seven-day divinatory reading experiment

Dear Living Dark reader,

This final installment of the bibliomancy experiment is arriving a day late because of an extremely full schedule at my college job over the past few days that has interfered with this, my real work. (I throw the latter characterization out there with tongue in cheek. Or maybe not? I’ll leave it for you to make your own surmise. Maybe I’ll leave it for me to do the same.)

Before I start, there’s this:

A free online launch party for Writing at the Wellspring

Weirdosphere, the online learning community, will be hosting a free celebratory launch party for my new book Writing at the Wellspring on Sunday, December 14, at 3 p.m. EST, and all of you are cordially invited. I’ll read a short selection from the book, and then we’ll open things up for conversation on the creative daemon, writing as spiritual practice, the challenge of silence, and the path of living and writing into the dark.

The launch party is free, and Weirdosphere has created a special event space for it. To participate—and to show support for the book launch—simply click the button below. You’ll be prompted to sign up for Weirdosphere and then register for the event:

This will be a casual gathering, so feel free to pop in and out as you wish. A recording of the event will remain available inside the event space for all registrants.

Gleaning One

And now, turning to the task at hand, I’ll note that the delay in this final installment may be oddly appropriate to the day’s draw. For when I stood before my office bookcase this morning and did my divinatory reach, I found that not just one but two books wanted to come off the shelf.

It hadn’t occurred to me at the start of this multi-day exercise that such a thing might happen, but I suppose it was a possibility all along. When I followed the procedure I laid out on Day One—reaching out with closed eyes and deliberately defocused attention to let my questing hand touch whatever book it encountered—two books offered themselves simultaneously. I even made a slight attempt to pull one away from the other, since I thought for a moment that the one on the left wanted to commend itself to my attention. But somehow they were stuck together. So I just went with it.

Interestingly, when I took them down and held them with eyes still closed so that I could separate them and then open to a random (“random”) page in each, I found no stickiness between their covers, no residue of, say, a peeled-off price sticker that might account for what had happened. They came apart easily, with no physical evidence to explain their previous magnetic pairing.

The upshot is that this final day’s gleaning is a dual reading, containing passages from two different books. Even so, I’ll present them separately for the sake of clarity.

Here’s the first:

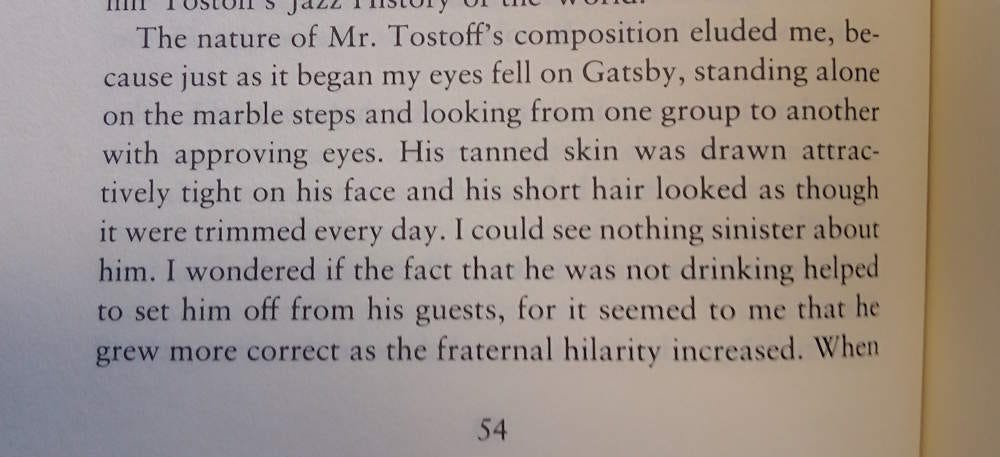

His tanned skin was drawn attractively tight on his face and his short hair looked as though it were trimmed every day. I could see nothing sinister about him.

It’s from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

As I proceed as always in the spirit of full disclosure and honesty, I fear this is the point in this experiment where my ruminations may elicit the question, “Has this guy actually read any books at all?” Because, in keeping with most of the previous days’ deliveries, this one presents me with something I haven’t read before.

What, you say? Cardin hasn’t read The Great Freaking Gatsby? How is that possible? Hasn’t every minimally literate English-speaking person in the Western hemisphere read that book? Well, I’m here to serve as proof that the answer is no. I have read parts of Gatsby. I’ve also seen parts of the 1974 movie adaptation with Robert Redford, as well as assorted scenes from director Baz Luhrmann’s over-the-top 2013 version with Leonardo DiCaprio in the title role. I’m passingly familiar with the overall story. I am of course well aware of the book’s important place in American letters and culture, and with the person and figure of Fitzgerald himself, and with the literary and cultural milieu out of which the book arose. But as for having read the novel through—well, nope. It just never came for me. Rather like Miller’s The Crucible. Though now I’m thinking it might.

So what about the delivered passage from it?

As I piece together the context within the novel, I find the passage represents narrator Nick Carraway’s first impression of Jay Gatsby. He is attending one of Gatsby’s extravagant parties, where he’s eager to meet the famous/notorious host, and he has just been in conversation with him for a short moment before realizing this is the man himself. As he steps back to take this in, his mental note that he could “see nothing sinister about him” refers to the rumors that have swirled around Gatsby regarding some hidden, dark past.

This is the moment where Gatsby steps onstage, so to speak, after having been someone whom Carraway and the reader have just heard about, to become an actual living presence. It inaugurates the relationship between the two men that becomes central to the novel’s unfolding. And Carraway’s initial impression of a handsome man with an innocuous appearance that doesn’t necessarily resonate with the rumors is ultimately framed as ironic when he becomes friends with Gatsby, only to find the man really does have a corrupt and shady past, and that his present appearance as one of the Jazz Age elite is a carefully crafted persona—an act of personal remaking for the purpose of achieving a specific goal: to win back Daisy, whom he obsessively idealizes.

Gleaning Two

And now let’s leave Gatsby for a moment and turn to the second textual gleaning:

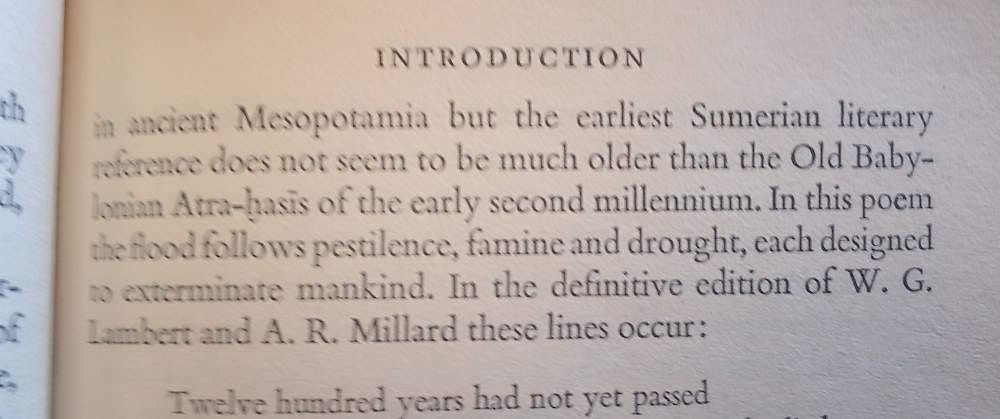

In this poem the flood follows pestilence, famine and drought, each designed to exterminate mankind.

(You may have noticed that the title I gave today’s post doesn’t appear in this gleaning. For explanation, keep reading.)

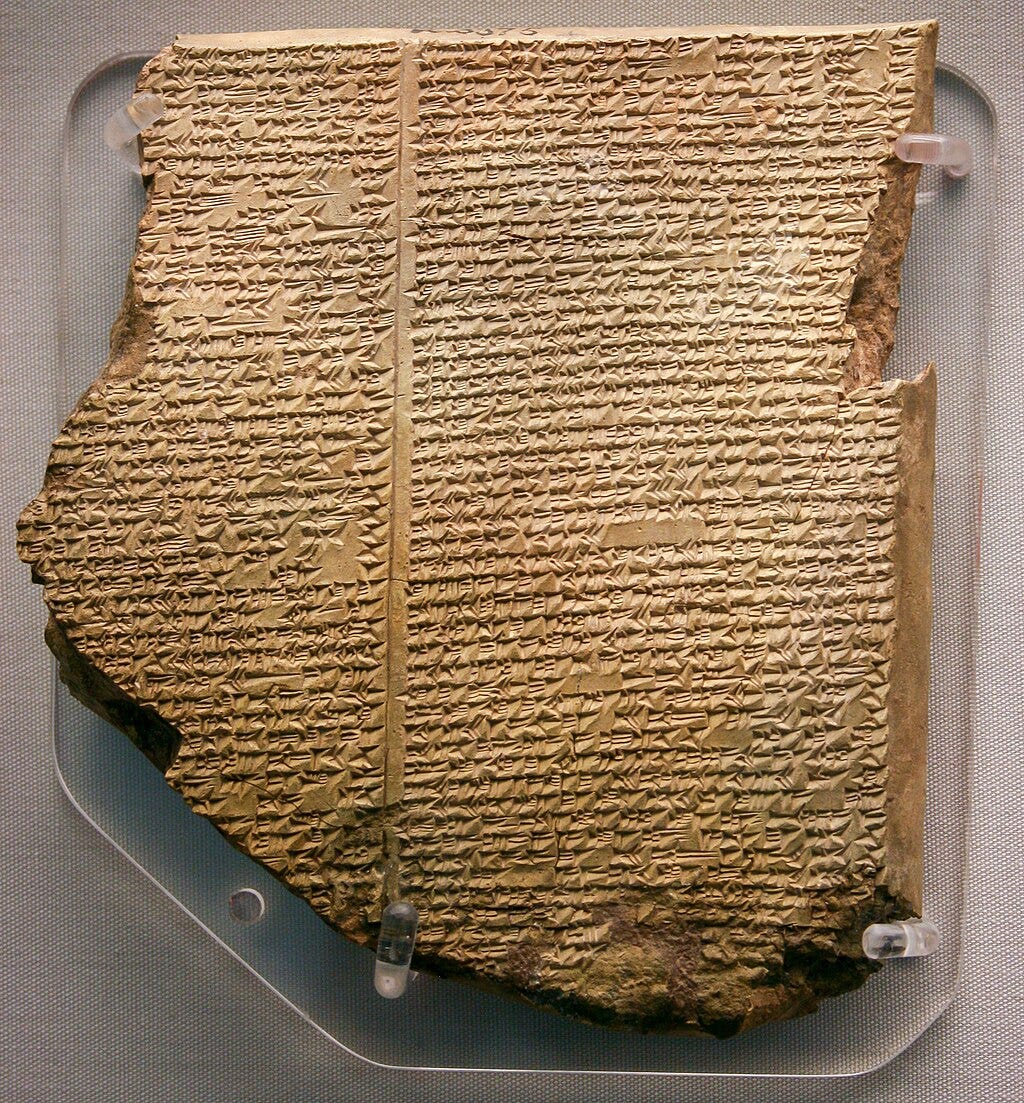

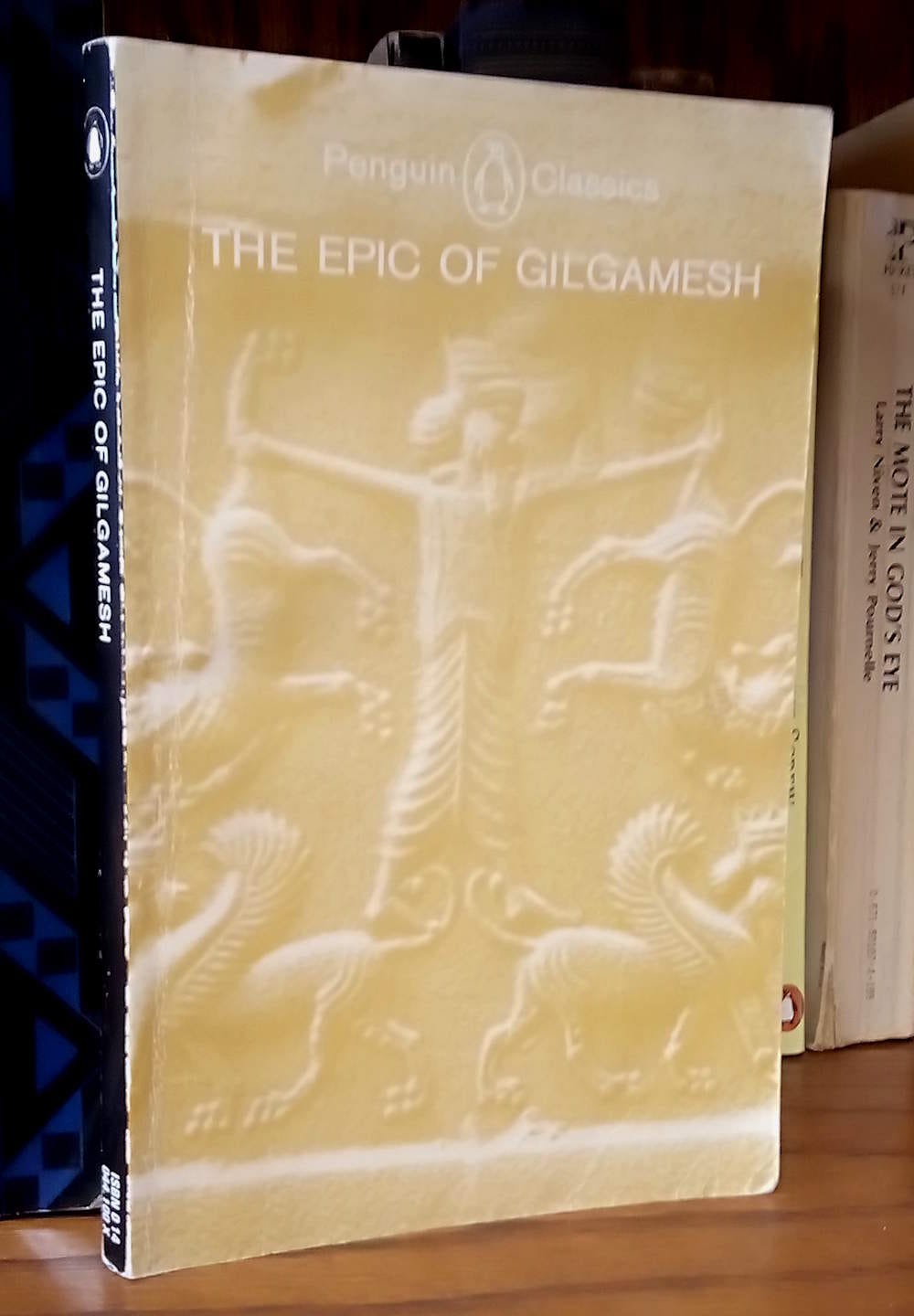

It’s from The Epic of Gilgamesh. Or rather, it’s from the late British archaeologist and prehistorian N. K. (Nancy) Sandars’s introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of this ancient, iconic poem. Sandars not only wrote the introduction but translated the poem itself, producing what went on to become a very popular version.

For those who don’t know or don’t remember, Gilgamesh is about a powerful but arrogant king—Gilgamesh, king of Uruk—who befriends Enkidu, a wild man created by the gods from clay to restrain Gilgamesh’s tyranny. They end up having some adventures together, one of which results in Enkidu being sentenced by the gods to death via a fatal illness. Afterward, Gilgamesh travels the world in a desperate search for a way to escape mortality. Along the way he faces monsters, gods, and the limits of human strength, eventually meeting a husband and wife who are the only survivors of the primordial flood brought by the gods to destroy humankind.

Ultimately, Gilgamesh learns from the man, Utnapishtim, that death is inescapable for humans, since the gods built it into them. In other words, it’s just part of our nature, and therefore our lot.

I am moved to quote some potent lines from Sandars’s introduction:

[The poem] is a mixture of pure adventure, or morality, and of tragedy. Through the action we are shown a very human concern with mortality, the search for knowledge, and for an escape from the common lot of man. The gods, who do not die, cannot be tragic. If Gilgamesh is not the first human hero, he is the first tragic hero of whom anything is known. He is at once the most sympathetic to us, and most typical of individual man in his search for life and understanding, and of this search the conclusion must be tragic.

And also:

There are many strands in the story, but this is the tragedy: the conflict between the desires of the god and the destiny of man.

And furthermore—and importantly—this:

Today ours is a world as violent and unpredictable as that of Assurbanipal, the king of Assyria, the Great King, king of the World, and of Nahum of Judea, and even of the historical Gilgamesh, the king of Uruk, who made war and sent out expeditions in the third millennium before Christ. The difference is only that for us the “swirling stream of Ocean” lies not over the rim of a flat horizon, but at the end of our telescopes, in the darkness they cannot penetrate, where the eye and its mechanical extensions turn back. Our world may be infinitely larger, but it still ends in the abyss, the upper and nether waters of our ignorance. For us the same demons lie in wait, “the dDevil in the clock,” and in the end we come back to the place from which we set out, like Gilgamesh who “went a long journey, was weary, worn-out with labour, and returning engraved on a stone the whole story.

As I piece all this together—both the Gatsby gleaning and the Gilgamesh one, not to mention the previous ones—I’m struck once again by the theme that has held steady over these seven days (or rather eight, given the altered schedule) of bibliomantic focus: that of storytelling, of relating, of the narratives we present and receive, project and imbibe, accept and reject, and of the multiple ways in which these can either open up or shut down our perception, and even our conception, of reality itself, either adding nuance and depth or foreclosing on them, and in any case potentially wreaking havoc upon what we take ourselves, and other people, and the whole world to be, whether for good or for ill.

I’m also moved here at the end to quote a line from the text of Gilgamesh itself, resonating back, perhaps, to Puck’s suggestion on Day One to avoid offense by considering a potentially offensive story to be nothing but a dream. The line gave itself to me as I was scanning through the book here in my office:

The dream was marvellous but the terror was great; we must treasure the dream whatever the terror; for the dream has shown that misery comes at last to the healthy man, the end of life is sorrow

It may take me a day or three, especially with a schedule that’s still busy ahead of me, to come up with a concluding reflection on all of this. In the meantime, please share your own bibliomantic gleanings and divinations, those of you who have been playing along.

Warm regards,

Preorder Writing at the Wellspring

Writing at the Wellspring is now available for preorder in its Kindle edition, with both Kindle and print editions arriving on December 15.

“[An] intimate journey into the mystery of creativity and spirit… Cardin weaves practical methods, personal stories, literary references, and mystical insights into a lyrical meditation on what it means to create from the depths of the soul… both deeply personal and universally resonant.” — BookLife review (Publishers Weekly)

“A guide for writers who welcome the dark and hunger for meaning.

— Joanna Penn“I can’t think of any [other books] that link the creative act so uniquely or persuasively with spirituality.”

— Victoria Nelson“A meditation on the silence and darkness out of which all creative acts emerge....A guide for writers unlike any other.”

— J. F. Martel“Important to any writer ready to see through the self illusion and realize the freedom this brings to any creative work.”

— Katrijn van Oudheusden

I do believe I have that very same edition of the Epic of Gilgamesh. I've given up playing, since I realized I was cheating. I was not reaching for books with my eyes closed. Perhaps I will try and replay this bibliomancy sometime. I've really enjoyed following your play and look forward to your conclusions.

Oh, boy. Just this morning I was just reading about Joseph Campbell and his background that led to the writing of The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Gilgamesh certainly falls into that bucket and I have been seeing the theme of this hero journey throughout this entire exercise. Today, (the last day of this encouraged exercise, and thank you very much for it) this is what I pulled.

………………..Hurt………………………

………………..Evil……………………….

……………...Glorious……………………

…………….Wonderful…………………

Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking by Malcolm Gladwell pg. 83

Gladwell was talking about our human tendency to make snap value judgements based on appearances. However, the passage struck me as a powerful commentary on life. What a way to end the 7 days.

Then I did something that may be cheating a little but I have recently been interested in testing what AI, particularly Chat GPT, is able to intuit based on what it knows about me. I use it almost everyday in editing and other basic tasks but I don't put much personal information in. I wondered what Chat would make of all these passages, so I gave it this prompt: "I have been engaged in a practice of bibliomancy the last week along with a blogger I follow. I have been trying to make meaning in my life of the passages I randomly pull from books on my office shelf. I will list them below. Please look for themes or meaning that I may have missed across the selections."

Here is what it gave back to me. I was somewhat stunned.

"Here are some themes and connecting threads that seem to surface when you lay these passages side by side. They read like stepping stones that form a quiet narrative about disorientation, discernment, identity, and courage.

1. Being led somewhere you did not intend to go

Your week begins with the Fellowship deep in the Forest, pulled away from their chosen path. They can no longer rely on direction or intention. This sets a tone of disorientation, a sense of being moved by forces not fully understood. It raises the question: when the path bends without your consent, what do you do with the uncertainty.

2. Trust and responsibility when you lack the full picture

Truman’s testimony introduces the idea of working within partial knowledge. Responsibilities remain heavy even when you cannot see everything that is shaping the larger situation. The theme repeats the idea that you may not have perfect clarity about the forces shaping your journey, yet your role still matters.

3. Impermanence and the pressure of time

Barbara Crooker’s poem introduces a shift. Suddenly seasons have changed, children are nearly grown, parents have vanished from the daily landscape. It deepens the early sense of disorientation but adds tenderness. Even when time feels as if it is slipping, the daily task is love. Not a grand quest, but a humble practice between morning and evening.

4. The deceptive nature of fear

Bradbury’s scene asks, What if the thing we fear is only frightening because we expect it to be. Sometimes the threat turns out to be ordinary, almost disappointingly human. There is a suggestion that not every shadow in the Forest is the monster you expect. Fear can distort perception.

5. Purpose responds to what you serve

Margaret Cameron brings a pivot point. You move from disorientation and fear into the realm of inner alignment. Her language suggests that purpose is not something that chases you. It answers only to your true nature. If you feed destructive forces, they answer. If you feed generative forces, they build for you even when you feel blind and wounded. This connects directly back to Truman’s partial knowledge and Crooker’s call to daily love: what you choose to serve shapes the path ahead.

6. Courage, struggle, and earned confidence

The Island Stallion adds energy and grit. The red horse stands unshaken in the face of challenge, confident because he has survived hard things. This is not naive confidence but forged confidence. It suggests that even when you are pressed or challenged, previous tests have shaped your backbone. The passage contrasts fear with the steady flame of experience.

7. Dichotomy and the rapid judgment of meaning

Gladwell’s scattered words offer the simplest frame, yet perhaps the most useful: Hurt, Evil, Glorious, Wonderful. It evokes snap judgment, but also how life tends to offer mixed signals. Experiences rarely fall neatly into one bucket. They can wound and uplift at once. They can frighten and clarify. They can feel like being lost in a forest while still moving toward something that matters.

Across the selections, a pattern emerges:

You begin lost, pulled away from the direction you thought you were going. You confront partial knowledge, shifting seasons, and fears that may not be what they seem. You are invited to consider the nature of purpose and the power of aligning yourself with what builds rather than what destroys. You see the image of earned courage standing steady in the face of challenge. And finally, you reach a page that simply names the tension of living: hurt and wonder, evil and glory.

This week of bibliomancy reads like a meditation on finding inner orientation when the outer world refuses to provide it. It hints that clarity may come not from perfect direction but from choosing what you serve, practicing love in the fleeting hours, and trusting the strength you have earned through earlier storms."

So, here is a guidebook to navigating this hero's journey I am on. The universe certainly is interesting. And kind.

Thanks for this, Matt. It has been meaningful in unexpected ways.