Creativity and the Edge of the Living Moment

On presence, imagination, and the strange feeling of waking up

Dear Living Dark reader,

I’m writing this to you with just a single point to make or perspective to pass along: The edge of the living moment is what creativity is all about. In fact, it’s what everything is about. Because, in point of fact, only the present moment is real. We commonly forget this and obscure it from ourselves by (mis)identifying with our thoughts, which pretend to deal with non-existent things that we call “the past” and “the future.” This confusion spins off into all manner of imaginary trouble that we insist on addressing as real. The result is paralysis, or at least difficulty, in both our creativity and our lives, two things that, at root, really aren’t two at all, but just different names for the same living experience.

Having said that, here’s the background to why I’m taking a moment to articulate these things in this communication.

First, yesterday I became aware of something Dena Evans had said in a recent post or essay at her online newsletter, Notes on Radiant Presence, which is devoted to discussing and exploring the work and words of the late, great nondual teacher Peter Brown. In “Waking Life Is Just Another Dream“—provocatively subtitled “Reality is the ultimate virtual reality machine”—Evans said the following:

Every apparent “thing” in my experience is in constant flux, and each moment is gone as soon as it appears, leaving little to no trace of what it seemed to be.

With only a little bit of acute observation of our direct experience, we can discover that the waking state only seems solid and constant. It’s actually a dynamic flow of experiential qualities that’s quite similar to the transient, illusory nature of a dream.

For those who have done some real, honest looking at their own experience—or, as Brown helpfully referred to it, their own experiential field —the truth of these words is self-evident. And it’s a truth that is thoroughly and fundamentally mind-blowing while also being the only thing we have ever really known.

Second, today a friend reminded me of a classic 1974 interview with Ray Bradbury (thank you, Georgia B. ) by pointing out that someone had shared a clip of it as an Instagram reel. The interview is titled Day at Night: Ray Bradbury, and you can easily find it at YouTube and elsewhere. Or directly below. The portion in question appears around the 11:00 mark and lasts about two minutes. In it, Bradbury lays out his central creative credo: that intellect and rationalization are the enemy of true art, and that real writing comes from feeling, immediacy, and emotional truth. I heartily suggest watching the whole half-hour conversation, which is simply wonderful.

Here’s a partial transcription of the section I’m talking about:

[The intellect is a] terrible danger because you begin to rationalize and make up reasons for things, instead of staying with your own basic truth: who you are, what you are, what you want to be. I’ve had a sign over my typewriter for 25 years now which reads, “Don’t think.” You must never think at the typewriter. You must feel…

What you’re trying to do as a creative person is surprise yourself, find out who you really are, and try not to lie, try to tell the truth all the time. And the only way to do this is by being very active and very emotional, and get it out of yourself, making lists of things that you hate and things that you love. You write about these then, intensely. And when it’s over, then you can think about it, then you can look at whether it works, or doesn’t work, or if something’s missing. And then if something’s missing, you go back and re-emotionalize that, so it’s all of a piece.

But thinking is to be a corrective in our life. It’s not supposed to be the center of our lives. Living is supposed to be the center of our lives. Being is supposed to be the center, with correctives around, which hold us, like the skin holds our blood and our flesh in. But our skin is not aware of life. Living is the blood pumping through our veins, the ability to sense and to feel and to know, and the intellect doesn’t really help you very much there. You should get on with the business of living.

Bradbury’s insistence on feeling over thinking is another way of pointing to the same truth: creativity lives only in the immediacy of presence, not in the abstractions of the intellect.

Third, the spontaneous reminder of the Bradbury interview came on the heels of my reading a new essay by Amanda Saint titled “The Day a Character Wouldn’t Stop Talking to Me.” In it, Amanda notes, trenchantly, that

our conditioning since birth in a material world has meant we’ve lost connection with the spiritual world. Maybe what we call “imagination” is actually the doorway to realms of awareness we’ve forgotten how to access. Maybe writers who channel voices aren’t making anything up at all, maybe we’ve just stumbled across the door and opened it.

Having these incisive expressions of core truths enter my awareness (or, in Bradbury’s case, re-enter my awareness) in quick succession elicited a deep response of: Exactly. Which returns us to the present moment and the flow of these words that you’re reading right now, and my note at the start of this missive about creativity being all about presence, which we only fully attend to when we recognize our tendency to try to abstract out of it or away from it—which actually can’t be done, since there’s no such thing as anything that isn’t present.

If that sounds confusing, it’s only because language always strains itself and grows convoluted when it tries to talk about these things. They intrinsically elude its semantic net. In fact, words, even when they seek to identify and clarify such matters, usually have the opposite effect, simply because of how they work. Still, here’s trying:

Our sense of assuming a critically reflective stance or mode, of stepping back “out” of the eternally present and unfolding moment, is just a convenient fiction, an assumed pose for the purpose of reflection and revision, like Bradbury described. It’s when we get lost in that convenient fiction of mental abstraction, when we actually identify with it and believe it to be real—and to be us, to be who and what we really are—that the trouble begins. Or at least there’s a palpable sense of trouble, a feeling of isolation and entrapment in dry-dead rationality, the skin-enclosed ego, as Alan Watts liked to call it.

And yet, even that feeling of entrapment and alienation is just reality, too, just another mode, another flavor within the infinitude of possible renderings that experience can produce and evince. The included aspect of discomfort, of suffering, that goes with this mode then prods us to seek its alleviation, which we eventually, in some form, “find.” Or rather, which eventually, in some form, manifests spontaneously as another rendering of experience, including the accompanying sense that it’s something “I” have successfully “achieved.”

It’s all kind of weird and fun in the end, isn’t it? Especially the part where we feel that we’re coming to recognize it, to notice this game that we play with ourselves. The game, too, is part of the infinite creative fluctuation that we purely and simply are. If anything can legitimately be identified as the “purpose” of the show—which in fact it can’t—it might be this feeling of waking up.

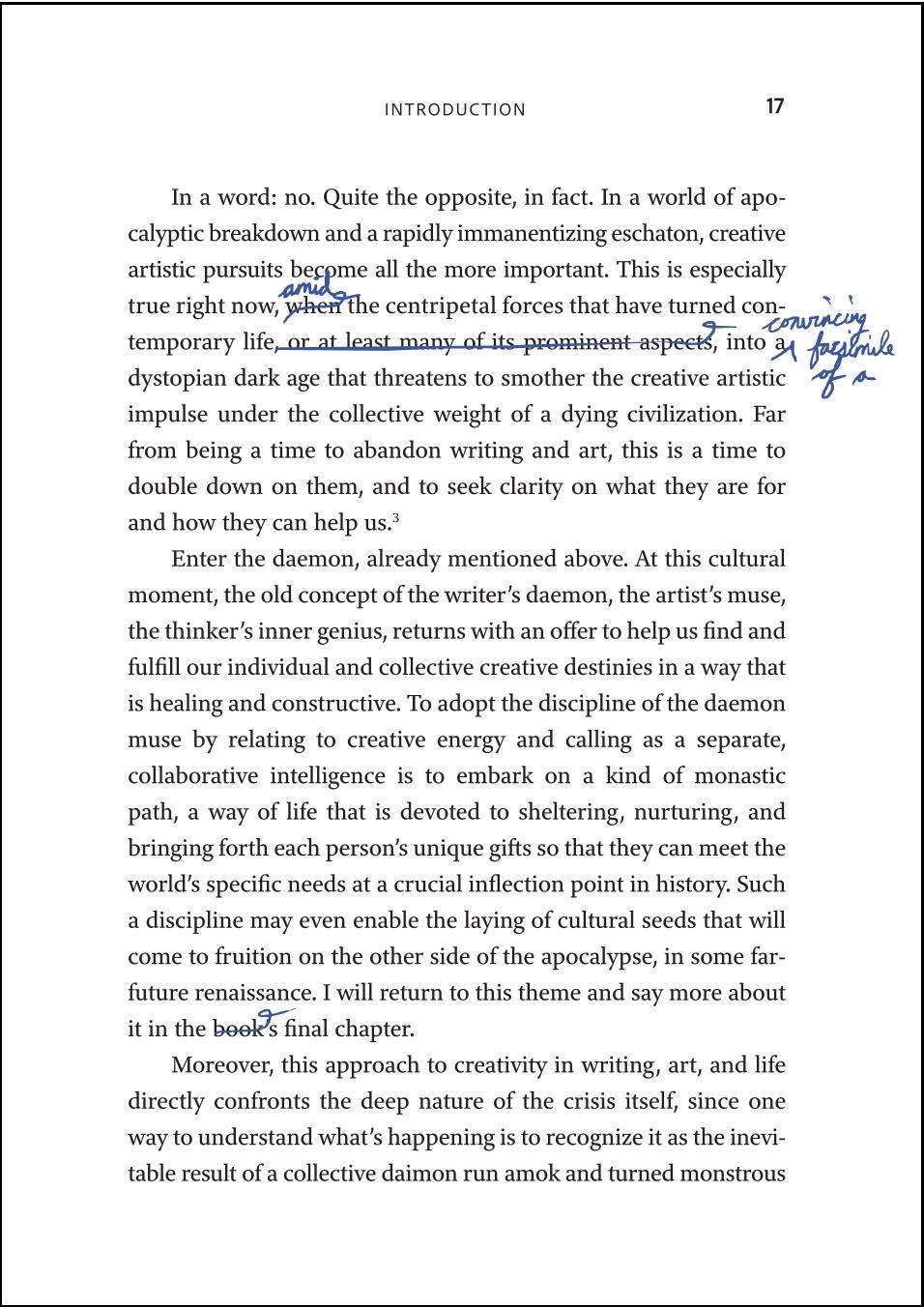

Writing at the Wellspring update: Handwritten corrections at the proof stage

Writing at the Wellspring is still on schedule for publication in November. For ongoing updates leading up to its launch, you can subscribe here (if you haven’t already) or follow the blog at my author website, mattcardin.com. Most recently, the book has been laid out and typeset.

Here’s one of the proof pages with my corrections and changes. It’s from the book’s introduction, where I talk about the role of art and literature and the importance of the muse or daemon in an age when real-world crises can make creative pursuits seem trivial.

From the text:

In a world of apocalyptic breakdown and a rapidly immanentizing eschaton, creative artistic pursuits become all the more important. This is especially true right now, amid the centripetal forces that have turned contemporary life into a convincing facsimile of a dystopian dark age that threatens to smother the creative artistic impulse under the collective weight of a dying civilization. Far from being a time to abandon writing and art, this is a time to double down on them, and to seek clarity on what they are for and how they can help us.

Enter the daemon, already mentioned above. At this cultural moment, the old concept of the writer’s daemon, the artist’s muse, the thinker’s inner genius, returns with an offer to help us find and fulfill our individual and collective creative destinies in a way that is healing and constructive. To adopt the discipline of the daemon muse by relating to creative energy and calling as a separate, collaborative intelligence is to embark on a kind of monastic path, a way of life that is devoted to sheltering, nurturing, and bringing forth each person’s unique gifts so that they can meet the world’s specific needs at a crucial inflection point in history.

As you can see, I’m correcting the proofs not with a computer, but by hand. I love the tactile sense of intimate connection to the text that this approach creates. Stephen King once talked about writing the entire first draft of Dreamcatcher by hand while he was recovering from his near-fatal accident and unable to sit at a word processor. He said the process reconnected him with the language in a way he hadn’t felt for years.

I feel the same. Working with text by hand, whether writing or editing, is the most intimate experience you can have with it. And it’s deeply satisfying for the clarity and connection it brings.

Warm regards,

Thank you for sharing this perspective. It is truly helpful for me regarding some of the areas where I often seem to become stuck.

I rewatched the full Bradbury interview. Kind of cool how, at about 16 minutes into it, he says something very similar (about the character being a medium in a seance with the author) to what Amanda wrote in her essay. Originally, it was just that initial portion I saw on instagram that made me think of her essay. Now it seems all the more relevant.

Enjoyed watching the full interview again. Thank you!

Brilliant ! This follows yesterday's visit with a close friend - both of us mired in the question "why persist in our art ? Neither of us show, neither sell nor have we the desire to prostitute our art for validation from gatekeepers nor for monetary gain." Yet despite the absence of outside observers and the avoidance of "the arts community", I'm compelled to continue making images. This has been a quandary for much of my life....castigating myself for being a coward or feeling jealous and bitchy about those "successfully" marketing their identities - my ego feeling thwarted and denied the pumping-up of admirers clamouring to validate me as "a voice of our times". It sounds pathetic. My friend astonished me with an allegory...a question..."we ( humanity ) are like a herd of elephants stampeding over the planet - all trying to leave our marks and trampling the world....shouldn't we rather be tip-toeing ?"