Of Phantoms and Forbidden Transmissions

My introduction to Mark Samuels's final book, 'Charnel Glamour'

Dear Living Dark reader,

Today’s post is exceptionally personal. You have already seen me talk many times in frankly personal terms about my experiences of the creative daimon muse, and my struggles with creative block and sleep paralysis, and my general experience of being a writer and human being who has embraced the viewpoint of living into the dark by forsaking the illusion of control in favor of greeting and affirming life as its unfolds in its paradoxical combination of inevitability and unknowability. But the present post is personal in a different way, as it has roots extending more than two decades into the past, and it deals with an old friend and fellow writer of weird and cosmic supernatural horror whom I lost five months ago. It also contains the full text of the introduction that I wrote to this friend’s recently published book, Charnel Glamour, which now stands, unexpectedly, as his final work.

You may or may not be familiar with the name Mark Samuels. I know the readership of The Living Dark includes many people who are and many others are not looped into the weird and supernatural fiction community. If you’re among the latter, Mark’s name may be unknown to you. But if you’re among the former, it’s likely that you’re aware of him. You may even be a fan.

I won’t court redundancy in this brief prefatory note by repeating things that I say in the text that follows, especially since, as you’ll see, it begins with a note that I added after the fact to acknowledge his death (which therefore renders the words you’re reading right now a preface to a preface to an introduction). But I will state, for the benefit of those who don’t know, that Mark was a major contemporary figure in this important subgenre of fiction and literature as a whole. He and I met at the turn of the millennium, before either of us had had our first book published, right when our writing careers were on the launch pad. Our connection occurred in the context of our mutual love of the works of Thomas Ligotti, who was already an iconic figure among readers of weird horror at that time, but whose transition to the status of a mainstream literary icon was still about fifteen years in the future. Mark and I found that our respective sensibilities, both for supernatural horror and for religious, spiritual, and philosophical matters, were closely aligned and deeply resonant with each other. We exchanged stories in manuscript and were fascinated to discover many overlaps and mutual concerns. It was rather thrilling. (I had a similar experience around the same time, starting a few years earlier, with Jon Padgett, author of the superlative The Secret of Ventriloquism, for which I also later wrote the introduction.)

Mark and I finally met in person at the 2002 World Horror Convention in Chicago, when he was part of a contingent of British writers who came over to the states for the event. Our rapport in person confirmed and extended the one we had enjoyed as correspondents.

This is one among many reasons why it touched me deeply when, in 2022, Mark contacted me to ask if I would be willing to pen the introduction to his then-forthcoming collection of stories, which bore the title Charnel Glamour. In the two decades since he and I had become friends, we had each had several books published—including our respective debut titles, his The White Hands and Other Weird Tales and my Divinations of the Deep—and we had both seen some measure of success. Mark’s work over the years had received praise from major figures like Ligotti, Ramsey Campbell, Ted Klein, and Michael Dirda, the Pulitzer Prize-winning book critic who has always been a friend to speculative fiction, and who wrote the introduction to Mark’s 2020 “best of” collection The Age of Decayed Futurity. I accepted Mark’s invitation with a mingled sense of gratitude and humility for having been asked. Then I took over a year to produce said introduction because of various life events that kept getting in the way and hampering my ability to find the right entrance into the task. The fact that it finally came together just in time for him to read the result before he unexpectedly passed away in December 2023 will remain, for the rest of my life, an enigma that sits there staring at me from the shadows with a mute sense of obscure meaningfulness, especially since the “way in” that I finally hit upon was to talk about my appreciation of Mark and his work in frankly personal terms, much as I have been doing right here. I didn’t intend to write a eulogy. But I can’t help feeling that this is what I unwittingly, to an extent, did.

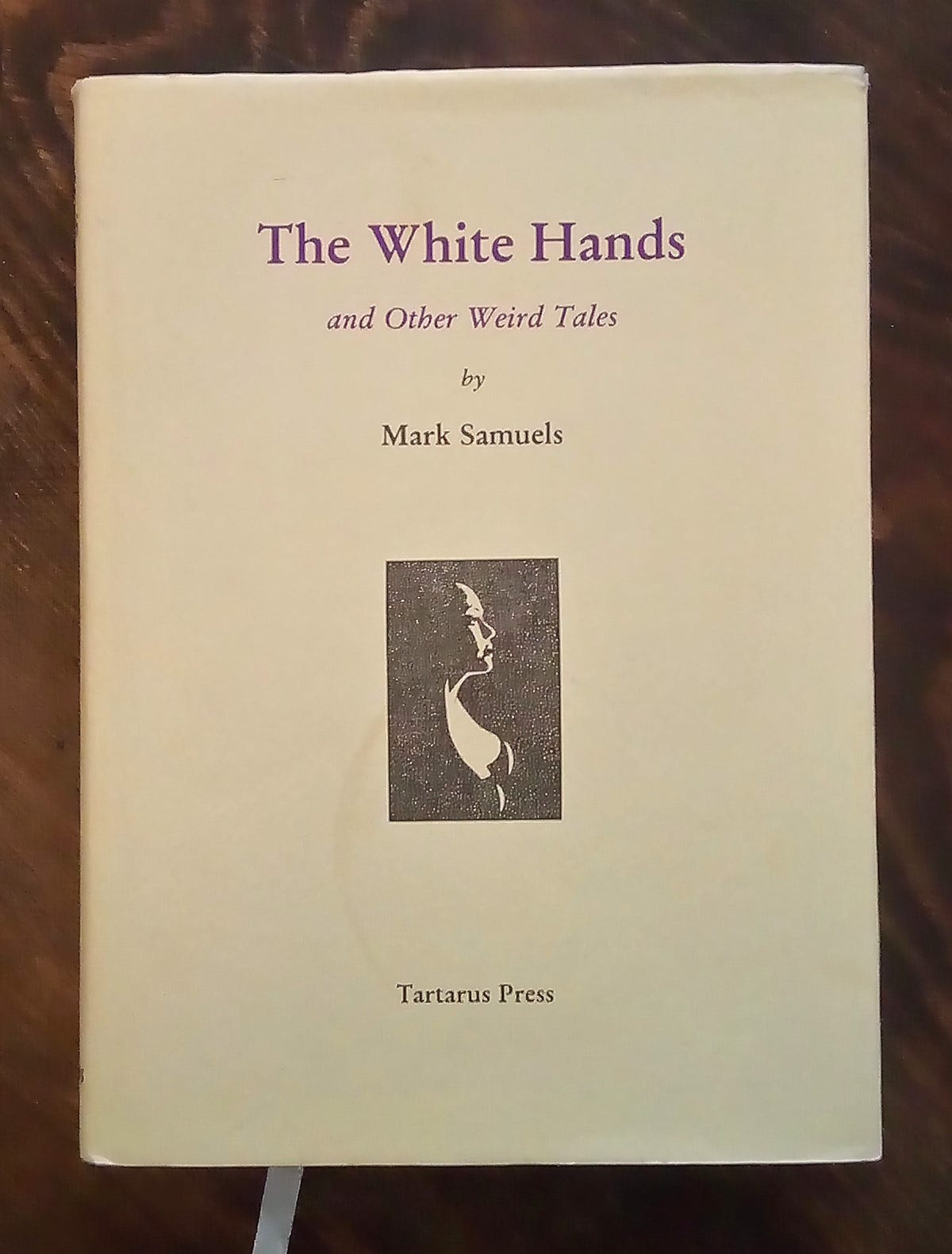

Here is my copy of Mark’s first published book, which I received directly from his hand at the 2003 World Horror Convention in Kansas City:

Here is a 2000 letter from Mark that I keep inside the front cover:

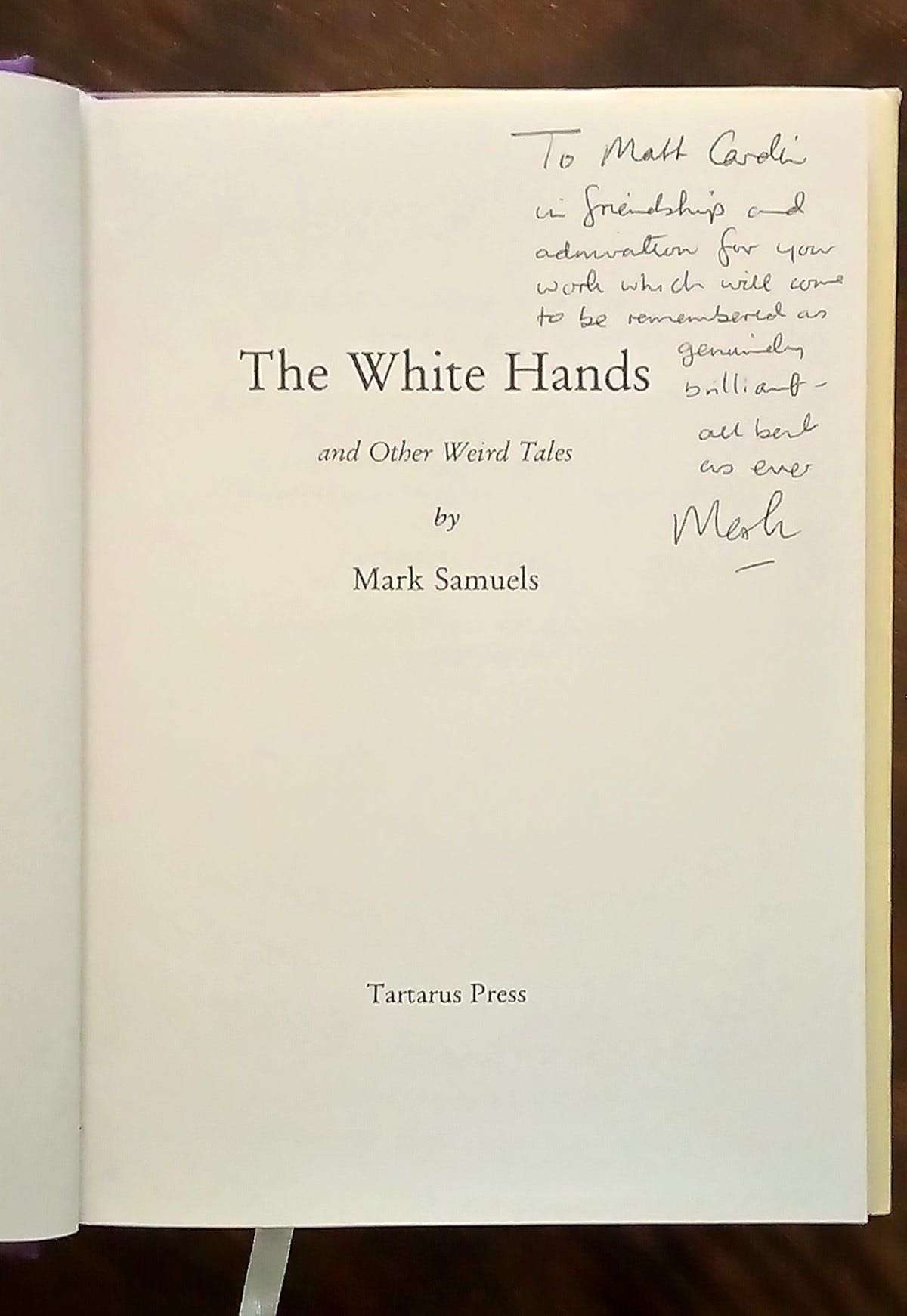

And here is the inscription that Mark wrote to me on the title page. I still remember sitting with him for a private moment in one of the convention hotel’s lounge areas 21 years ago, right in the wake of this book’s publication, as he handed me a copy with an attitude of quiet humility and expressed doubt about its prospects for success in the world—doubts that, as the public and critical reception of The White Hands went on to demonstrate, were wildly unfounded.

Upon receiving word of Mark’s death from our mutual friend Quentin S. Crisp, four days after I had sent Mark the text of my introduction to Charnel Glamour, I took my copy of The White Hands down from its shelf, held it in my hands, opened it to reread Mark’s inscription, and then reread his letter to me from 23 years ago. He is still there in that letter, and in the pages of that book and all his others, the lurking and pervading presence of the author suffused throughout the worlds of his words. I take comfort in that.

And I hope those of you who have found interest in this newsletter with its focus on unraveling the intersection of writing, creativity, the daimon muse, and nonduality, with a sometime infusion of numinous dread, will recognize in Mark, as portrayed in my comments above and the Charnel Glamour introduction below, a kindred spirit whose artistic vision and philosophical and spiritual concerns are resonant with your own path and perspective.

Warm regards,

FORBIDDEN TRANSMISSIONS:

An Introduction to Charnel Glamour by Mark Samuels

by Matt Cardin

PREFACE TO AN INTRODUCTION

The following introduction to the book you are now reading took me eighteen months to write, counting from the date when Mark first invited me to do it (May 21, 2022) to the date when I performed the final edits and sent him the finished text (December 1, 2023). Various factors conspired to extend the matter to such length. Mark and I exchanged several emails during the interim. And now, in retrospect, I find myself pondering and wondering—deeply, helplessly, and not a little speculatively—about the obscure forces that dictate the rhythms and schedules of our lives, our creative energies, and our personal relationships. For when I agreed to write this introduction, and when I unexpectedly took so long to do it, and when I used the occasion to reflect on the fact of Mark’s and my twenty-plus-year friendship, which reached back to the beginning of the present millennium, before either of us had published our first books—see the thoughts on this in the text below—I did not know, and could not have known, that Mark would die just hours after receiving and reading it.

“Many thanks for sending over the introduction, which I think forms a very splendid entrée indeed to the book,” he said to me in an email dated Saturday, December 2, after 5 p.m. London time. “I'm much moved by the sentiments therein.” I wrote back to say that I was glad he was pleased with it. We exchanged another couple of emails that same day. I mentally settled in to await the book’s publication a few months down the road. And then, four days later, on Wednesday, I received an email from a mutual friend, Quentin S. Crisp, informing me that Mark had passed away over the weekend. It had happened overnight on December 2–3. I absorbed the news with shock and then watched my mind work out the timing: Mark had departed this world very shortly after our last exchange of messages. In fact, one of the last things he had ever read was my introduction to his next book.

There were many people who were much closer to Mark than I was, both physically and personally, and their loss is much deeper than mine. But the improbable timing of these things in relation to my own long friendship with him continues to arrest me with feelings of sadness and strangeness. I suspect it always will.

In an essay titled “Beyond the Beautiful Darkness,” which I published in May 2014 at The Teeming Brain, Mark described the upshot of the atheistic outlook that he inhabited until his late twenties: “Death meant oblivion, an end to all suffering. At any moment I could put an end to my life and embrace absolute nothingness! I was truly free. I had no master but myself. I controlled the real power in this universe: death, not life.” He then explained how his atheism was comprehensively upended and replaced, through a combination of reading (Arthur Machen, C. S. Lewis, Hilaire Belloc, G. K. Chesterton) and personal mystical experiences, by the Roman Catholicism that remained his spiritual home and philosophical center ever afterward. Such intimations were not initially welcome. “I became perturbed,” he said of the persuasive provocations that he perceived from Machen et al. “I loved my beautiful darkness, with nothing in it but myself, and I loved having no doubts whatsoever.” And yet he also felt this certainty to be stifling: “I had locked myself into a prison cell with nothing but the darkness I had come to love. I knew everything that could be known, because it was everything I had chosen to know.” Thus, his spiritual and philosophical conversion came as an experience of light and liberation: “cracks in the walls of the cell began to show, and a little light poured through them,” followed by what he experienced as the cell’s wholesale implosion.

For Mark, this led to a final answer that satisfied. It also motivated him to write the stories that now constitute his contribution to weird and supernatural horror—not as a means of proselytizing for a particular religious worldview, but as a means of exploring the ramifications and potentialities, particularly the dark ones, of living in a supernaturally charged universe.

To whatever extent it is possible for a person to see, directly and fully, the reality that lies behind the veil of the mind and body, and the hidden spiritual sun that is the source of the universe’s numinous glow, and the mystery that imparts to everything a sheen of charnel glamour, Mark now sees and knows them.

In one of the more widely known passages of the New Testament, the apostle Paul said, “For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known.” To whatever extent it is possible for a person to see, directly and fully, the reality that lies behind the veil of the mind and body, and the hidden spiritual sun that is the source of the universe’s numinous glow, and the mystery that imparts to everything a sheen of charnel glamour—to whatever extent such things can actually be seen or known, not dimly in a mirror or partially by a mortal, but unveiled in their primal actuality by the removal of the limitations of finitude, Mark now sees and knows them. Or at least I like to think he does. And in this thinking, I am happy for him.

Matt Cardin

Pyatt, Arkansas

February 2024

FORBIDDEN TRANSMISSIONS

If a book is a meal, then the purpose of an introduction is to set the table. It is to provide the reader with the utensils that will enable enjoyment of the repast to come. As I was mulling over how to accomplish this for Charnel Glamour, it occurred to me that a sense of context, of scope and placement within the author’s career and thought, might be the most helpful thing I could provide. But then I realized that I might be projecting my own sense of the book onto you, my imagined reader. Maybe I’m too tangled up in this matter to be able to see it objectively.

Because, you see, Mark Samuels and I became friends before his first book, The White Hands and Other Weird Tales, was published. In fact, I still have a handwritten letter from him, dated two years prior to that publishing event, in which he discusses the book’s prospective contents, which were then not entirely settled. This letter sits beside me on the desktop as I type these words. I also still own and cherish the copy of The White Hands that I received directly from Mark at the 2003 World Horror Convention.

So right now, these two decades later, when I have agreed to introduce Mark’s latest collection of stories, I find that I feel personally entangled in the task. I also find that I am beset by a sense of numinous vertigo that has increasingly come to characterize my experience of time’s paradoxical passing—paradoxical because the present always remains present, and I always remain I, even as time flows inexorably past—during that same span. And maybe, therefore, when I write these words, I’m not actually trying to help you. Maybe I’m not even thinking of you at all. When my instinctive move in reflecting on Mark’s new book is to think back to where his career began, and to remember our early acquaintance, and to consider how this informs my own reading of Charnel Glamour, maybe I’m just trying to explain to myself how twenty years can possibly have passed, and why the memory of Mark’s first book still resonates with me all these years later, and how it is that he writes weird supernatural horror stories that patch directly into my apprehension, amplified by the passage of time, of the strange fact that we live in a world of phantoms in which we ourselves, despite our presumed solidity, may be the very source of spectrality.

In 2006 I interviewed Mark for the blog I ran at that time. He told me that his desire to write had originated with his discovery of Lovecraft at age fifteen. “Lovecraft, for me,” he said, “made the world itself much more interesting, providing it with a sense of charnel glamour for which I’d been searching during my youth.” (Yes, those italics have been added by me.) However, he later “discovered the work of Arthur Machen, which, I think, has been an even greater influence upon my adult life and attempts at fiction.”

When I asked him whether his personal beliefs, including his religious affiliation and his preference for Machen’s mysticism over Lovecraft’s nihilism, had ever found their way into his stories, he replied: “I am a Roman Catholic. But I really wouldn’t dream of trying to incorporate any moral teaching into my weird fiction. I am not a proselytiser. . . . I don’t really see my writings in the supernatural horror genre as representative of my religious beliefs, or of the totality of my experiences. I see them as almost exactly the reverse, as if these fragments of a sub-created literary universe must, inevitably, be wilfully nightmarish in order to succeed aesthetically.”

You don’t enter Mark Samuels’ universe of charnel glamour to notice or dwell on his influences. You enter it to be swallowed whole.

I think it is somewhere among these data points, as perhaps cross-fertilized by the influence of a few other masters of weird fiction both historical and contemporary, including Thomas Ligotti, that Mark’s authorial sensibility can be triangulated. (A tangential but not unimportant observation: Ligotti came to weird fiction in an opposite order from Mark’s, discovering and liking Machen first but then finding his primary influence in Lovecraft.) And yet, having said that, I also want to say that such comparisons and tracings of influences are in the end superfluous, since in Mark’s stories one encounters a presence and a feeling that is distinctly different from what one can find anywhere else. You don’t enter Mark Samuels’ universe of charnel glamour to notice or dwell on his influences. You enter it to be swallowed whole.

Any attentive reader of Mark’s work has noticed the recurrence of certain consistent elements and themes over time. My sense is that these come together in a singularly potent way in this collection. From its outset, the book announces itself as being set within a recognizable world of Mark Samuels’ creation, consisting of a haunted English geography and, in several of the stories, a set of characters, locales, and plot elements that hark directly back to earlier stories and books, including his signature title story from that first collection twenty years ago. If I read it aright, there is even one semi-meta story that is implicitly framed as having been written by Lilith Blake, whom connoisseurs of the Samuels canon will well remember.

This story and several others expand on the nightmarish spiritual-supernatural vision that Mark laid out in “The White Hands,” detailing a circumstance in which “supernatural literature, expressed in its highest degree . . . is a form of initiatory rite into higher orders of being,” and in which “the power of an acutely concentrated imagination, one centred upon death and the macabre, [is] the means of releasing occult power.” It is a world where death itself offers no escape from the horrors so released, since the body’s demise is actually “a doorway to the beginning of stupendously greater terrors undreamt of by the still-living.” A universe where the fact of living in a metaphysical order that evinces “the pre-eminence of the Weird over the Mimetic” means that dangerous lunatics are empowered “to create the only true art,” which is not mere entertainment but “the very stripping away of the veils which separate us from the abysses of eternity and infinity,” and which may lead to “murder as the quintessence of ecstasy, terror as the height of irresistible fascination, fear as the epitome of delight, and bodily evisceration as supreme craftsmanship.”

Other established Samuels themes abound. A weird/Gothic fixation on the implicitly or potentially disturbing fact, presence, and nature of technology and its positioning within human thought and culture. The intrinsic creepiness and uncanniness of effigies of the human form. The persistence and influence of a haunted past on a bleak and horrified present. Strange and sinister religious cults. The fatuous spiritual emptiness and galling moral deadness of modernity. The displacement of the human personality by another, darker entity or intelligence. The supernatural potency of books and television as carriers and transmitters of malign and transformative realities. These are all present in this new collection. As always, they are expressed in Mark’s signature measured prose, which, to my American ear, anyway, embodies such a palpable voice of Britishness that I can almost hear him reading it aloud.

There is also a certain, striking newness to some of the stories herein. The opening one lampoons, in high weird/supernaturally horrific fashion, the pretensions of critical theory, grounding the examination of old texts within the academic outlook of a protagonist who in effect buries the supernatural aspect, until the pressure causes it to erupt uncontrollably and in inextricable connection with the protagonist’s own pretensions. At the other end of the collection, in the final story, a protagonist whom readers of one of Mark’s earlier collections will find oddly familiar, though strangely altered, tracks down a bizarre and ancient religious cult whose identity is ingeniously framed. It’s a piece of ironic thematic inversion that demonstrates what weird horror is capable of in the hands of a writer with a definite personal philosophical and spiritual orientation who happens to be committed to the art itself, for its own sake.

So all this and more constitutes the Samuelsian weird fictional cosmos. It is a place where I can sense some of the most pointedly personal intimations of metaphysical fear from throughout my lifetime peering through the elements of the various narrative vehicles that Mark has constructed for conveying his vision. Readers of such stories—readers like you and me—find pleasure in this emotion of weird and numinous fear. At the same time, we also recognize that stories like this are about more than just delivering a few literary fictional pleasures. They carry the ring or scent of truth. They feel like revelations, like forbidden transmissions, like windows or doorways to something that is real, but that we are otherwise not allowed to acknowledge or talk about. In short, they feel a lot like the supernaturally potent books-as-carriers that show up in many of the stories themselves.

There is really no conclusion to this self-indulgent excuse for an introduction, no way to end it that will signal my successful setting of the table and represent your cue to dig in. Maybe that is only appropriate, since, as I said, I’m probably not even thinking of you but trying to articulate my own deep response to this book. I will simply end by stating that the universe of charnel glamour to which these stories point is eerily familiar to those whose private imaginings have always been tuned to that frequency—that is, to people like you and me (which I suppose means that I must be thinking of you after all). Mark himself tuned in long ago and began relaying that numinous signal to the rest of us. This latest collection of stories represents one of his clearest transmissions yet.

Matt Cardin

Pyatt, Arkansas

December 2023

Charnel Glamour by Mark Samuels is published by Chiroptera Press. A paperback edition with additional content will be issued in 2025 by Hippocampus Press.

Thanks Matt: I haven't read any of Mark's work (although I was aware of him), but you have very much persuaded me to dive into it. Saddened to hear of his death.

This was very moving to me.

Thanks for posting it.