Oswald Chambers: Sacred Unleader

In which I share the first chapter of my never-published doctoral dissertation

Dear Living Dark reader,

Today’s post is unlike any that I have shared with you before. Though I previously published one of my unpublished academic papers, what I give you today is a bit of a “higher stakes” piece than that: the entire first chapter of my Ph.D. dissertation on Oswald Chambers, which I think and hope may prove of interest.

If the name “Oswald Chambers” doesn’t ring a bell, this is unsurprising, for reasons the chapter itself makes clear. I myself first became acquainted with Chambers back in 1995, when a Southern Baptist pastor gave me a copy of Chambers’s classic daily devotional My Utmost for His Highest. At the time I was an obsessive reader of spiritual and philosophical books from multiple traditions, and Chambers’s book unexpectedly rocked my world with its spiritual power and depth of insight, expressed within the vocabulary and worldview of evangelical Christianity. Something about it resonated with me on a fundamental level, and the man and his work went on to become an enduring companion in my life. But I didn’t know until it happened that he would one day become the focus of the most intense and extended academic project that I have ever undertaken.

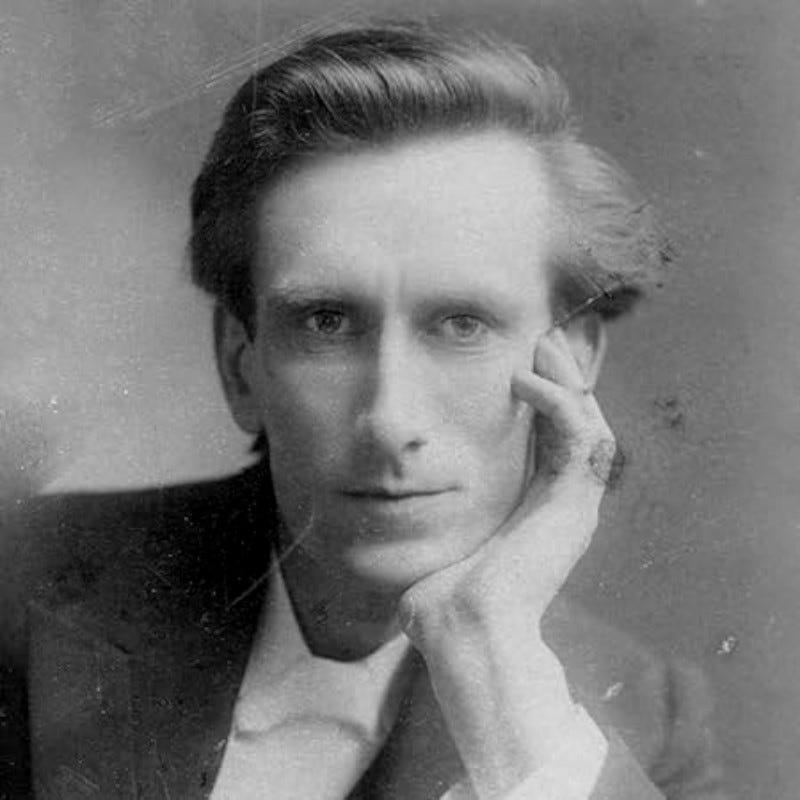

Chambers was an early twentieth-century Scottish preacher and missionary who was both wholly devoted to his native Protestant Christianity and constantly driven to, as it were, transcend it. His formal spiritual orientation consisted of a mixture of his British Baptist upbringing with the holiness movement theology that later profoundly influenced him. Additionally, his outlook was deeply informed by his extensive engagement with literature and his intensive study of philosophy and psychology. He was also a gifted artist who had originally intended to make a career of it. In his maturity he was frustrated by what he perceived as the performative emotionalism, rote mental patterns, and shallowness of understanding that characterized many Christians and churches. He saw, thought, and felt more deeply and lucidly than most when it came to spiritual matters, and his core drive was to bring this depth to other people and spur them to see past standardized concepts and rote religiosity, to the point where real, transformative Truth could erupt in their souls and reshape their thoughts and lives.

I completed my dissertation on Chambers and my Ph.D. in leadership studies in the summer of 2019. (It was the very same month when, through an odd coincidence of timing, my supernatural horror fiction collection To Rouse Leviathan, which had been in development for nine years and on hiatus for six or seven of those, finally saw publication.) The text clocked in at 114,000 words and just under 400 pages. Both the dissertation and the Ph.D. coursework had devoured my life for the preceding two years, a fact that I’m reminded of when I revisit the dissertation’s acknowledgments page and reread the final, personal acknowledgment that I included at the bottom of a list of otherwise academic ones: “Finally, and most importantly, I am sincerely grateful to my wife, Teresa, for enduring a seemingly interminable two years during which I effectively became the Invisible Man around our house as I spent more time with the ghost of Oswald Chambers than with her.” I wrote those words five years ago. To date nobody has read them, along with the dissertation text itself, except for me and the members of my dissertation committee, plus one person who had provided some helpful research assistance. This, despite the fact that I poured as much of myself into that project as I have ever poured into any of my books.

The December 15 entry in My Utmost for His Highest contains the following, which resonates as strongly in my spirit as it did when I first read it nearly thirty years ago:

If you cannot express yourself on any subject, struggle until you can. If you do not, someone will be poorer all the days of his life. . . . You must struggle to get expression experimentally, then there will come a time when that expression will become the very wine of strengthening to someone else; but if you say lazily, “I am not going to struggle to express this thing to myself, I will borrow what I say,” the expression will not only be of no use to you, but of no use to anyone. . . .

Always make a practice of provoking your own mind to think out what it accepts easily. Our position is not ours until we make it ours by suffering. The author who benefits you most is not the one who tells you something you did not know before, but the one who gives expression to the truth that has been struggling for utterance in you.

The principle Chambers articulated in those passages is one that has stood in back of my entire writing career. Since the late 1990s, I have been struggling to perfect the expression of the ideas, insights, and emotions that seem determined to move me, and that arrive accompanied by a motivation to communicate them to others. Along with the likes of Lovecraft, Ligotti, Alan Watts, C. G. Jung, Robert Anton Wilson, and a few others, Oswald Chambers has been among the authors whose works have served to provoke my mind and amplify my effort and ability to find the right words.

The title of my dissertation is Sacred Unleader: Leadership in the Life and Thought of Oswald Chambers. Here is its abstract:

This study examines the leadership principles that are embedded and embodied in the life and thought of Oswald Chambers. Starting from the observation that Chambers has been largely neglected by the field of academic scholarship for a full century even as his most famous book, My Utmost for His Highest, has become one of the most influential texts in modern Christianity, the dissertation looks at Chambers through the lens of leadership studies to uncover the principles that he both taught and practiced in his various leadership roles as a tutor at Dunoon College, a missionary and itinerant speaker in the transatlantic holiness movement, principal of a residential Bible college in London, and YMCA chaplain to British Commonwealth troops in Egypt during World War I. Chambers developed a pointedly Christological understanding of leadership that elevated spiritual formation over practical training and that recommended a corresponding nondirective style intended to put followers in direct personal contact with God. He also mounted a strong critique of organizations and institutions, which he regarded as intrinsically liable to interpose themselves between individuals and God by posing as ends in themselves. The study finds that his leadership philosophy can be accurately characterized by combining certain modern critiques of contemporary Christian organizational practices with the category of the sacred leader arising out of recently developed typology of Christian leadership, to arrive at the concept of the “sacred unleader,” one who leads, and who teaches others to lead, in a way that cultivates spiritual depth among followers while deliberately opposing and overturning conventional worldly notions of authority, power, and hierarchy.

And here, after all that throat clearing, is the introductory chapter. Though the original contains thirty footnotes, for this online Living Dark version I have removed the ones that consist solely of source citations, leaving only three that contain contextual information for the main text. I have also removed several sections that are solely of technical academic interest, including “Purpose, Focus, and Research Question” “Approach, Perspective, and Thesis” (I have kept only the “Thesis” portion), and sections offering notes on such things as the dissertation’s organization and chapter development, the handling of Chambers’s texts in light of the evolution of his thought, and British versus American spellings.

INTRODUCTION to “Sacred Unleader: Leadership in the Life and Thought of Oswald Chambers”

by Matt Cardin

When Oswald Chambers died in a hospital in Cairo, Egypt, on November 15, 1917, he could not have known that he would posthumously become one of the most influential Christian leaders of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Not only was the book for which he would become most widely known, the daily devotional My Utmost for His Highest, not yet published, it was not even written. It was Chambers’s wife, Gertrude “Biddy” Chambers, a trained stenographer, who would go on to create My Utmost—along with dozens of additional books—from her verbatim shorthand notes of the talks, lectures, and sermons Oswald had delivered to multiple audiences in multiple settings over the seven-year span of their marriage. My Utmost, published in Britain in 1927 and the United States in 1935, would become the most famous of them all, attaining an almost mythic status among American evangelicals, especially Southern Baptists, and influencing such major organizations as the Oxford Group and Alcoholics Anonymous, along with such prominent public figures as Billy Graham and President George W. Bush.

That this should have happened while Chambers remained unknown to the majority of Britons and Americans for most of the century following his death is one of the more noteworthy examples of the cultural Balkanization that has come to define Western life in recent decades. To a numerically large but proportionally small and isolated population of Christians, especially in America (but also elsewhere; My Utmost has been translated into more than forty languages), Oswald Chambers is something of a fabled saint, a gargantuan, looming figure who has shaped the personal spiritualities, thought lives, emotional patterns, and religious outlooks of millions of individuals in a way and to a degree that is exceeded only by the influence of the Bible itself. To everyone else, he is not even a “blip on the radar.” Stephen N. Dunning, professor (now emeritus) of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania, has offered an effective description of this cultural position of simultaneous fame and obscurity: “Among non-evangelicals I often encounter a blank response—Oswald Who?—and that is understandable, for there has never been a single scholarly article or book written about him. But in evangelical communities his writings are the daily fare of countless millions, as the translation and publishing records attest.”1

One of the most prominent aspects of Chambers’s character and career was his assuredness and influence as a leader. By all accounts, he was a powerful speaker, a charismatic presence, and something of a human dynamo. His intense energy and exuberance were rounded out by a combination of innate gifts and extensive training, and this led to his being placed in multiple positions of formal leadership responsibility and authority, in which capacities he greatly impressed those who encountered him. The Rev. J. M. Ridge, for instance, wrote of being introduced to Chambers in 1906 by Reader Harris at a meeting of the League of Prayer, the interdenominational Christian renewal organization, founded by Harris, that played a prominent role in the late-nineteenth- and early twentieth-century British holiness movement. Ridge stated that the “outstanding impression of that great meeting was Mr. Chambers’s own testimony. He reminded you of the apostle Paul, a teacher and leader of the first rank.” The Rev. David Lambert, a close friend of the Chamberses, described his early acquaintance with Oswald in the context of a Christian preaching and teaching mission event as “days of God’s right hand. The spiritual power [of Chambers’s teaching], the practical-ness, the Scriptural statement of the truth, the sane appeals to saints and sinners, were to me, a young minister, an education in how to do God’s work in God’s way.” A Mrs. Donnithorne, who was a student at the residential Bible Training College (BTC) in London run by Oswald and Biddy, and who traveled to Zeitoun, Egypt, to work with them during World War I, said, “In many ways Zeitoun was a unique YMCA centre, because Mr. Chambers was a unique leader.” Lord Radstock of the National Council of the YMCA described the way the imprint of Chambers’s person and presence was visible throughout the YMCA huts at Zeitoun, stating flatly, “Oswald Chambers was a magnetic personality.” Four decades after Chambers’s death, the Rev. Donald Coggan effectively summarized these earlier assessments by referring to Chambers simply as “that wise leader of men.” Coggan’s opinion on the matter may be regarded as carrying some weight; at the time he wrote those words, he was the Bishop of Bradford, and he would go on to become the 101st Archbishop of Canterbury.

To a numerically large but proportionally small and isolated population of Christians, Oswald Chambers is something of a fabled saint, a gargantuan, looming figure who has shaped the personal spiritualities, thought lives, emotional patterns, and religious outlooks of millions of individuals in a way and to a degree that is exceeded only by the influence of the Bible itself. To everyone else, he is not even a “blip on the radar.”

In death, Chambers’s leadership influence has been extended by My Utmost and, to a lesser but still significant extent, his other Biddy-created collaborative works. Given the importance of these books for that large but relatively isolated segment of Christian readers, and given that this isolation currently appears to be shifting and weakening as Chambers’s name seeps out into the wider culture in ways to be discussed in this dissertation, there is significant value to be found in a study of the leadership principles embedded and embodied in the man’s life and thought.

Oswald Chambers: A Biographical Sketch

As this study will encompass not just Chambers’s ideas and teachings but the life experiences out of which they developed and in which he deployed and refined them, a brief account of his biography here at the outset, followed by a consideration of his posthumous rise to fame, will be useful for setting the scene and establishing a context. Oswald Chambers was born to Clarence and Hannah Chambers in Aberdeen, Scotland, on July 24, 1874. The youngest of seven siblings (an eighth child, an older sister, died before his arrival), he was raised in an intensely religious family. Both Clarence and Hannah were devout Baptists. Hannah had been baptized by none other than Charles Haddon Spurgeon, while Clarence was a Baptist pastor who had been one of the first students to study at Spurgeon’s famed Pastor’s College in London, later renamed Spurgeon’s College. The family relocated several times during Oswald’s youth—to Stoke-on-Trent, England, in 1877; then to Perth, Scotland, in 1881; and then to London in 1889—as Clarence moved through a series of Baptist religious jobs of an evangelistic, pastoral, and administrative nature. At age fifteen, Oswald himself experienced a personal conversion after hearing Spurgeon preach at London’s Metropolitan Tabernacle, home of the Pastor’s College. He soon became involved in formal Christian outreach work at Rye Lane Baptist Chapel in Peckham, where he and his family had become members. He excelled at this work, and also at music and art, the latter of which led to his earning a certificate at London’s National Art Training School (today’s Royal College of Art).

In 1895, Oswald left home to study art and archaeology at the University of Edinburgh. Although he found his studies and the general atmosphere of the university to be stimulating, during his first semester he entered into a time of anguish and spiritual searching as he felt increasingly drawn away from art, which he had conceived in considerable detail as a divine calling, and toward a career as a preacher. An overnight vigil at Arthur’s Seat, a hill located in the middle of Edinburgh, resulted in an intensified sense of God’s call to a preaching ministry and the conviction of having heard God’s voice (an incident to be discussed further in Chapter Four). When he returned to his room at the university the next morning, he found that his mail contained a copy of the annual report from Dunoon College, a small theological and ministerial training college near Glasgow. Interpreting this as a sign, Chambers took the momentous and, as it seemed to his friends and family, rash and foolhardy step of leaving the highly respected University of Edinburgh in 1897 to study at Dunoon College under its founder, principal, and sole faculty member, the Rev. Duncan MacGregor.

Chambers rapidly established himself at Dunoon as a prodigy, becoming a philosophy tutor and impressing all with his agile mind and charismatic presence. However, he also entered into another season of spiritual crisis, this one more agonizing than the first, when he prayed for the “baptism of the Holy Spirit” (a term to be defined and discussed in Chapter Two) after hearing a lecture on the subject by the Baptist preacher and Keswick holiness exponent F. B. Meyer. By Chambers’s own account, after that prayer he was plunged into an extended “dark night of the soul” as all sense of God’s presence deserted him and he was made piercingly aware of his own sinful heart. He eventually emerged from this crisis with a new sense of spiritual empowerment and focus, accompanied by a dramatically deepened conceptual and emotional understanding of the gift of the Holy Spirit, the place of humanity in relation to God, the importance of times of spiritual darkness, and the general meaning and import of his Christian faith.

He was plunged into an extended “dark night of the soul” as all sense of God’s presence deserted him and he was made piercingly aware of his own sinful heart. He eventually emerged from this crisis with a new sense of spiritual empowerment and focus.

For the remainder of his short life, he devoted his time, attention, and energy to Christian teaching and preaching, with his basic message about sanctification, including sanctified thinking and holy living, identifying him squarely with the nineteenth and early twentieth-century transatlantic holiness movement. He made missionary journeys around Great Britain and to the United States and Japan. Between 1905 and 1911, he became one of the most important speakers for the aforementioned League of Prayer. In 1910 he married Gertrude Hobbes, whom he nicknamed Biddy (derived from B. D., itself an initialism for “Beloved Disciple”), and who would keep that name for the rest of her life. Under the auspices of the League of Prayer, they opened and jointly ran the residential Bible Training College in London’s Clapham Common from 1911 to 1915. Then, in response to the outbreak of World War I, they closed the college and, with their young daughter, Kathleen, left London for Zeitoun, Egypt, where for the next two years they led a YMCA ministry to British Commonwealth soldiers.

To the great shock of those who knew him as a vibrant and indefatigable presence in the military camps, Chambers died in Egypt on November 15, 1917, from complications following an emergency appendectomy. Although he had taught and preached to thousands of people during his brief span of 43 years, he had seen only two books and several pamphlets of his work published during his lifetime, and there was no indication that his reach would extend any farther than it already had.

Posthumous Celebrity

At the time of Oswald’s death, he and Biddy had already edited and returned the publisher’s proofs of his first book, a study of the Book of Job titled Baffled to Fight Better. The two previous books that bore his name, consisting of his transcribed teachings on biblical psychology and the Sermon on the Mount, had been published in America without his direct involvement. Baffled to Fight Better was the first to come directly from his and Biddy’s hands. After its publication following Oswald’s death, Biddy teamed with a group of friends to commence the editing and publishing project to which she would devote the rest of her life. Beginning in Egypt and then continuing in England after she and Kathleen returned home, she transformed her notes on Oswald’s sermons and lectures into dozens of books bearing such evocative titles as The Shadow of an Agony (1918), The Psychology of Redemption (1922), and Shade of His Hand (1924). She also published many of Oswald’s talks in the Bible Training Course Monthly Journal, which she launched with the help of a friend and colleague in 1932. The Chambers group was eventually incorporated in London in 1942 as the Oswald Chambers Publications Association (OCPA).

Assorted details of the OCPA’s history will be examined in Chapter One, but in the present context the significant thing is the way My Utmost began to insert its way deep into American evangelicalism almost immediately upon the publication of the U.S. edition in 1935. In her 2017 memoir about the influence of Chambers and My Utmost on her life, the American writer Macy Halford provides a succinct description of the trajectory of this influence when she explains how the book’s early success in America was due in no small part to the fact that it promptly fell into just the right hands for boosting its cultural profile. The list of its early supporters in the United States “reads like a who’s who of the conservative evangelical movement,” including such luminaries as Richard C. Halverson, Henrietta Mears, Bill Bright, and Billy Graham. These and other important figures contributed to the spread of My Utmost in various ways: by quoting from the book, teaching from it, recommending it, and distributing copies of it. Separately, Bill Wilson and Bob Smith, the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous, also played a major role when they adopted a practice from the Oxford Group, the influential early and mid-twentieth-century Christian organization that served as a kind of seedbed for the formation of AA, by making My Utmost one of the standard books for studying at group meetings.2

From these beginnings, My Utmost became a near-ubiquitous fixture in conservative American evangelicalism in a way and to an extent that was equaled by no other modern devotional book. Several generations of American Christians grew up with Chambers’s devotional serving as their primary supplement to scripture. The book “has grown to become one of the most important books in Christianity outside of the Bible itself.” Moreover, new developments in recent decades, including the reprinting of Chambers’s books and the publication of new Chambers-related literature, have rejuvenated his status and reputation for the twenty-first century and have brought his name and work to the attention of the general public.

My Utmost for His Highest became a near-ubiquitous fixture in conservative American evangelicalism in a way and to an extent that was equaled by no other modern devotional book.

Perhaps most tellingly, today the “Rotunda of Witnesses” located in the museum at the Billy Graham Center on the campus of Wheaton College—a major center of evangelical intellectual activity that is sometimes referred to as “the Harvard of evangelical colleges”—displays nine banners commemorating iconic heroes of the Christian faith. Eight are historical figures of universally recognized world significance: the Apostle Paul, Justin Martyr, Gregory the Great, St. Francis of Assisi, John Wycliffe, Martin Luther, Blaise Pascal, and Jonathan Edwards. The ninth is Oswald Chambers.3

The Need for This Study

Despite all this, and as mentioned above, Chambers’s work has received vanishingly little scholarly attention. To date, only a single dissertation, focusing on Chambers’s preaching style, has been devoted entirely to him. He has been mentioned or cited in many academic publications, but such instances are usually tangential and fleeting. As he communicated in a highly quotable style, often his appearance in a given article, book, thesis, or dissertation will take the form of a mere snippet of text lifted from one of his books, usually My Utmost, and repurposed as an epigram or aphorism. This lacuna in the literature represents a distinct opportunity for the academic who wishes to traverse new ground. Chambers was intensely intellectual, deeply reflective and philosophical, widely read, full of fascinating and sometimes original ideas, and driven by a sense of divine calling and an energetic enthusiasm that made him seem a formidable presence to those who knew him. He also lived during a richly tumultuous time in world history. In short, his life and work are ripe for examination along all sorts of scholarly lines. As indicated by the foregoing considerations, one of the most fruitful such lines leads through the field of leadership studies.

In this regard, it is important to note a striking fact about the audiences to whom Chambers spoke in life and to whom his books continue to speak today. A large portion of his published teaching consists of transcribed and edited talks, lectures, lessons, and sermons that were delivered to and aimed at an audience of current and future Christian leaders. My Utmost, for instance, was derived primarily from lectures and devotional talks that he gave to students at the Bible Training College. Many of these dealt with such matters as preaching and formal discipleship. At the same time, some of the material in the same book comes from talks and sermons that he delivered to soldiers at Zeitoun. This interesting duality in his original audiences points to a significant fact about his overall focus and approach as a Christian leader: Although only four years of his life were devoted to the full-time teaching and training of full-time Christian preachers, missionaries, and other kinds of leaders, he preached, taught, and spoke in largely the same terms to more general audiences, and he had a gift for communicating effectively with both types of listeners.

A kind of rhetorical duality pervades My Utmost, in that it can be read as both a conventional devotional text for a general audience and a spiritual training manual for pastors, preachers, and missionaries.

In 1907, for instance, when he was staying and teaching at God’s Bible School in Cincinnati, Ohio, he was scheduled to speak only to pastors each morning during the June camp meeting.4 However, the crowds were so large that the meetings were opened to the general public. One who witnessed Chambers’s performance in this circumstance later wrote about his successful handling of it, describing him as “that stalwart piece of sanctified Scotch granite” who “captivated men and women” with his presentations. A decade later, one of Oswald’s YMCA colleagues in Egypt recounted hearing him say that entertainment was not necessary to attract soldiers to his YMCA tent, as he could “get a crowd of Australians night after night attracted by nothing but the message of Redemption.” Upon traveling to Zeitoun to see for himself, the colleague “found that the unheard-of thing had come to pass.” Large numbers of soldiers who were not particularly religious showed up for a week-night religious talk that consisted of “no appeal to the emotions, no cant religious phrases, no anecdotes, just a flow of clear, convincing reasoning—stark sincerity, speaking with the authority of deep personal experience.”

This ability of Chambers to communicate effectively to both types of audiences—formal Christian leaders, including those in training, and the general population—and to do so without significantly shifting the register in which he addressed them, imbues his published words with a unique quality. In effect, his way of preaching and teaching was always aimed at Christian leaders, whether actual or potential. He was always speaking to people in a way and on a level that encouraged and helped them to know Christ better, to live holy lives, and to communicate and represent these things to others. This is visible right in the pages of his most widely known book. A kind of rhetorical duality pervades My Utmost, in that it can be read as both a conventional devotional text for a general audience and a spiritual training manual for pastors, preachers, and missionaries. Many entries speak directly to preachers about the significance of their calling and the best ways to fulfill it. And yet the book has been studied and cherished for nearly a century by a multitude of lay readers. The point here is that the leadership principles in back of Chambers’s approach are distributed pervasively throughout My Utmost and his other books, which therefore broadcast to a popular audience a type and level of teaching that is usually regarded as more appropriate for seminarians. A number of the books, including Approved unto God, Called of God, Disciples Indeed, and So I Send You, consist entirely of material taken from classes that he taught at the BTC for future preachers and missionaries. This dissertation proceeds from the assumption that because of this, there exists a distinct need for an in-depth exploration of Chambers’s leadership principles, which he not only demonstrated in his own capacity as a leader but directly taught, and still teaches today, to a multitude of listeners.

Thesis

This dissertation concludes inductively that, based on examination of the evidence, Chambers can accurately be described or classified as a “sacred unleader.” The first word in that term refers to his classification within a leadership typology called the Leadership Stool model. Developed by David T. Olson, this model posits six possible types of Christian leader, with Chambers being classified as a “sacred leader.” The second word, “unleader,” is a helpful term proffered by both Lance Ford and Taylor Field to describe a type of leader whose approach manifests what has sometimes been called “upside-down leadership,” which confronts, inverts, and confounds conventional top-down hierarchical models and attitudes based on organizational authority and power. Linked to this thesis is the fact, which becomes apparent throughout the dissertation, that the record of Chambers’s life and thought manifests a number of paradoxes or seeming contradictions. Throughout his brief career, he insisted on taking a “hands-off,” nondirective approach to the spiritual deepening, development, and formation of others—the subject that was far and away his primary concern. And yet, at the same time, he emphasized the importance of a leader’s influence on followers, and he framed this in a way that effectively casts everyone as a leader in some capacity, all while warning about the influence of charismatic leaders, of which he was one. He counseled an attitude of fundamental wariness toward religious organizations, warning that such organizations are always liable to coalesce into wrongly conceived ends of their own and thereby abandon or eclipse their true spiritual purpose, even as he served at various points as the most sought-after speaker for the League of Prayer, the co-founder and principal of the BTC, and a chaplain for the YMCA. He made curious choices about his career and life path that confused his family, friends, and followers. And he linked his idea of Christian leadership to discipleship, regarding the two phenomena as fundamentally inseparable. Presiding over the whole of this rich stew of thought and activity was his conviction that Christ, ultimately, should be recognized as the supreme and even sole leader of the church.

Value of the Study

The value of the study arises from the intersection of Chambers’s place and reputation in conservative American evangelicalism, and increasingly in the wider culture at large, with the evolving and advancing field of leadership studies. As already stated, Chambers, through the crucial agency of Biddy and the OCPA (and, more recently, the American publisher Discovery House), has posthumously served as a significant spiritual leader to millions, including individuals who have themselves served in important positions of leadership authority. Understanding the nature of the leadership principles embodied in his life and embedded in his thought can shed light on the nature of his extensive influence. It may also add to the field of leadership studies itself.

A concluding note for Living Dark readers

The story of Oswald’s “dark night” experience, mentioned in the biographical section above, is frankly fascinating. So are his general reflections on what he called “the treasures of darkness,” a phrase he drew from the Book of Isaiah to refer to the benefits of times of spiritual crisis and depression. Based on his own experience, along with his study of the Bible, world literature, and the literature of psychology and philosophy, he maintained that such times of darkness are the necessary doorway to spiritual awakening and deepening, since without them we remain falsely satisfied with shallow lives and outlooks built on untruth. In a future post I may share the section of my dissertation that talks about this.

Warm regards,

This quote appears in an unpublished and undated paper from the 1990s by Dunning titled “The Ambiguity of Experience: Oswald Chambers’ Evangelical Spirituality,” 2, Box 2, Folder 4, Oswald Chambers Papers (SC/122), Special Collections, Buswell Library, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL. In his assertion that Chambers had never been the subject of “a single scholarly article or book,” Dunning may have been unaware of a 1941 article about Chambers that appeared in the journal Theology (and that is referred to several times in this dissertation). Or maybe that article and/or journal does not qualify as scholarly in the way he meant. In any case, his point is valid. On the general topic of Chambers’s neglect in scholarly circles, in a phone conversation on April 5, 2019, Dunning attributed this to the fact that Chambers is most commonly known for My Utmost and that this runs up against a widespread bias in academia against evangelical devotional literature.

My Utmost had played a crucial role in the Oxford Group. As recounted by Kathleen Chambers, Frank Buchman, the group’s founder, once contacted Biddy directly to request the production of a special edition of the book to be distributed to all members.

NEW FOOTNOTE, January 2024: In the five years since I wrote this dissertation, more figures have been added to Wheaton College’s Rotunda of Witnesses.

God’s Bible School was affiliated with the holiness movement, for which the tradition of “camp meetings,” for the purpose of nurturing and renewing Christian holiness and holy living, were a fixture, dating from the 1860s.

I was not able to comment on this back when I read it because I was not yet a paid subscriber to your substack account. Now that I am, I can write what I would have weeks earlier, which is this…

Thank you for sharing your dissertation. It was quite a long read, but I read every word and enjoyed all of it, including your opening and concluding statements. I especially appreciated mention of his period of spiritual crisis. Of the very little I previously knew about Chambers’ life, that was not a part.

Given that I own only two gifts from my late father (one strand of faux pearls he bought each of his three daughters when we stood up as bridesmaids in our brother’s wedding and one daily devotional book… My Utmost for His Highest), and given the fact that I have experienced my own moments of spiritual crisis, this post was meaningful to me. Thank you for taking the time to post it.

I think Oswald Chambers was one of those rare individuals whose life struggle is to let the Immense shine through their little "self", in the process manifesting an energy that irresistibly calls those around them to the same struggle, the undoing of the ties of "personality", the highest realisation of love.