The Book I Would Like to Be Buried With

Reflections on the book I want to take to my grave

Dear Living Dark reader,

Some years ago—fourteen, to be exact—I was one of several horror writers who were invited to contribute a post to the blog Horror Reanimated for a series titled “The Book I Would Like to Be Buried With.” The theme was clear: What book do you love so much, what book feels like such an inseparable part of you, that when your time eventually comes, you’d like to take it with you to the grave?1

This decade and a half later, when I reread what I wrote for that series, I realize it may represent the moment when I finally managed to explain to my own satisfaction why I’m simultaneously and helplessly drawn to both the literature of fear and the literature of faith. To supernatural horror as much as supernatural longing. To numinous dread and numinous delight, inextricably intertwined and basically indistinguishable from each other. So that makes this relatively minor short essay a significant moment in the evolution of my self-understanding. (And what about you? Have you ever written anything like that yourself? I mean something that advanced your self-understanding in some key way, maybe even when you weren’t expecting it to.)

Rereading this piece also reminds me that I basically cheated by sidestepping the boundaries of the assignment and finding a way to mention not just one book but a mini-library of them.

This week I have decided to exhume my burial book essay and share it with you. So here it is, my Living Dark friends, in a slightly but pervasively rewritten form that brings certain matters up to date and optimizes the prose style to reflect the way my inner voice and editorial ear are now calibrated these many years later.

Warm regards,

P.S. There’s an active Living Dark chat thread where you can share your own burial book.

P.P.S. To repeat the ritual disclosure: I’m an affiliate of Bookshop.org, which helps local, independent bookstores thrive in the age of ecommerce. I’ll earn a commission if you click through one of the book links in this post and make a purchase.

The Book I Would Like to Be Buried With

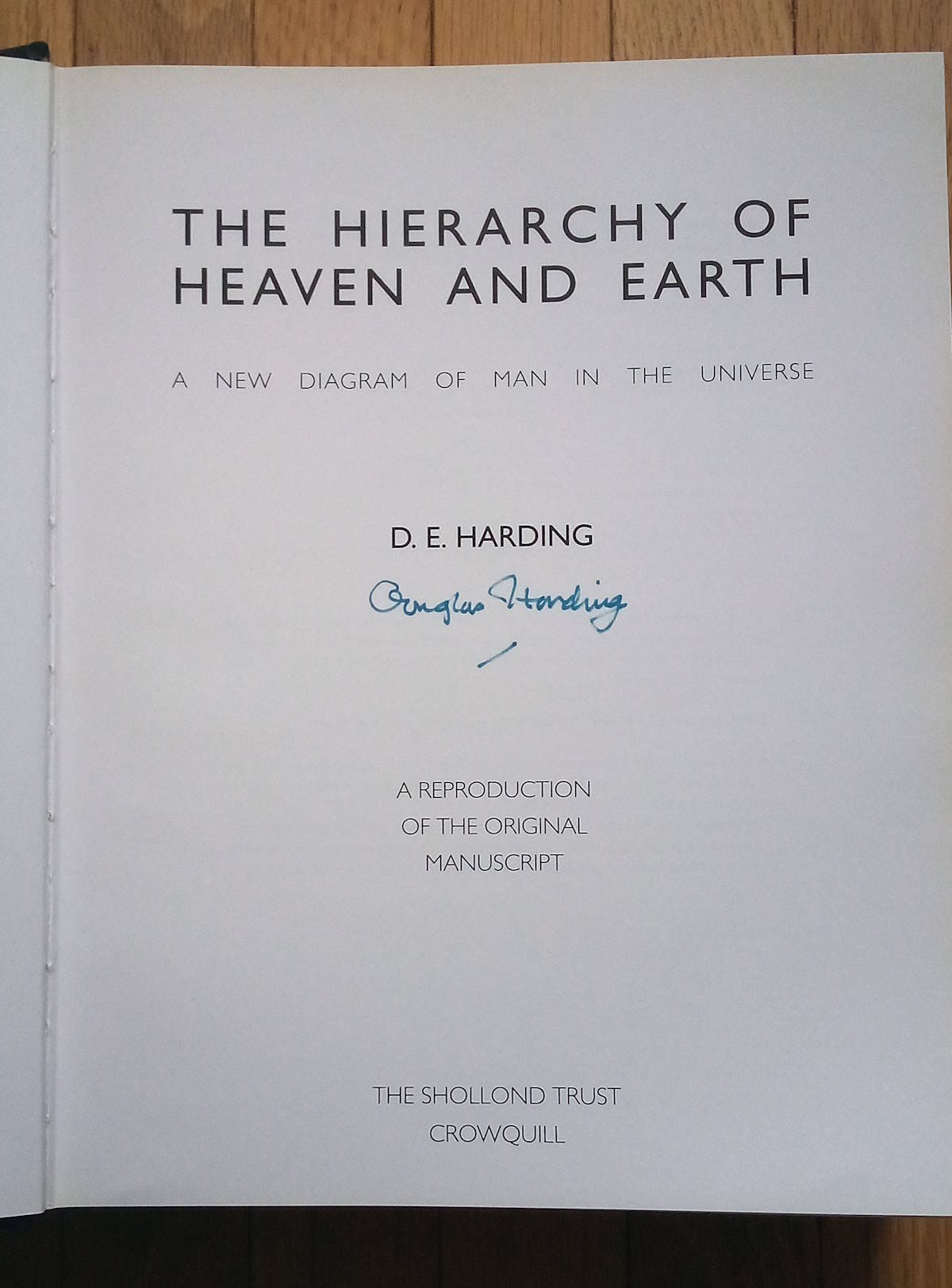

The book I would like to be buried with is the unabridged facsimile edition of the late British philosopher Douglas Harding’s frighteningly outsized and terrifyingly brilliant über-tome The Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth—which I have never read.

Let me explain.

Choosing a book that you would like to be buried with is a significantly different challenge from the familiar question of your “desert island book,” the one book you’d like to have with you if you should ever find yourself stranded on a remote island with nothing but time and solitude on your hands. The proper choice in that case is a book that you love so dearly, and whose contents you find so inexhaustible, that you wouldn’t mind rereading it over and over again, without access or recourse to any other book, for the rest of your life.

For a burial book, by contrast, the proper choice has more to do with how you would like to be remembered. After all, you won’t be reading as you lie there returning to the earth. You won’t get to enjoy whatever book you decide to take with you to the grave, except maybe in the anticipatory satisfaction you might feel during the run-up to your demise as you reflect that this book and no other will serve as a kind of appendix to the epitaph carved on your headstone if anyone should ever happen to dig up your coffin and disturb your mortal remains. “Hmm,” this future grave robber might muse as he gazes down on a nest of rotted pages, which in turn rest upon a mass of nastier stuff below. “So he was a Dan Brown fan.”

So then, the choice of a burial book requires some careful thought, because it’s not the same as choosing a favorite book.

Why, then, would I choose a book that I have never read? The answer involves the fact that this whole challenge doesn’t make for an easy choice at all, especially when a multitude of options automatically suggest themselves to an inveterate reader like me. Take H. P. Lovecraft’s complete fiction, for instance. I mean, after all, HPL’s stories are gloriously available today in various handsome volumes, including many that contain S. T. Joshi’s corrected texts and thus blow away the lovable but suspect Ballantine paperbacks I was weaned on. But if I chose a volume of Lovecraft’s stories, this would only properly accompany an epitaph like “He loved cosmic horror” or “Dreamer and dreader of the great gulfs beyond.” Though such a description might be accurate as far as it goes, it would be a bit too circumscribed to encompass my whole sensibility.

Or what about Thomas Ligotti, whose work has affected me more deeply than that of almost any other writer? Maybe I should choose for my burial book The Nightmare Factory, or Grimscribe, or Teatro Grottesco, or maybe even The Conspiracy against the Human Race. These are all ostensibly good candidates, all deeply important to my emotional, intellectual, and artistic development. But again, they would be a bit too circumscribed to encompass the whole. And they would say more about Tom than about me.

Okay, so what about the Bible? It’s definitely a contender, since that ancient library of religious texts, written over millennia and crammed together between two covers to create the illusion of a single, univocal scripture, is crucially implicated in my deepest life patterns, both inner and outer. I was raised in a cultural atmosphere of “high” scriptural regard, where the Bible was unquestioningly regarded as inerrant and authoritative. Then I broke through to a more nuanced view—or perhaps it broke through into me—and have spent my life ever since wandering around in a deepening daze at the wonders of this ancient record of archetypal spiritual encounters woven together with accounts of bloody pre-modern moral, political, and cultural codes, all tending toward a cosmic revelation of shattering scope. So that’s all wonderful stuff. But then, being buried with a Bible might send the wrong message, too, so impenetrable is the thicket of cultural presumptions surrounding it. My imagined grave robber might lift my coffin lid, see the book on my breast, and mistake the person I used to be for a typical “Bible thumper,” an inhabitant and representative of the religious-cultural backwater that Alan Watts used to refer to in memorably inflammatory fashion as “the lunatic Protestant fringe.” And that wouldn’t do at all.

Speaking of Alan Watts, several books by him are worthy candidates. The Wisdom of Insecurity. Psychotherapy East and West. Beyond Theology. This Is It. The Supreme Identity. The Book: On the Taboo against Knowing Who You Are. Each of these has been of great personal significance to me. And if Alan is in the mix, then why not Eckhart Tolle with The Power of Now? Or Huston Smith with Forgotten Truth or Beyond the Post-Modern Mind? Or Shunryu Suzuki with Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind? Or Jan van de Wetering with The Empty Mirror and A Glimpse of Nothingness?

This could quickly turn into an impromptu imitation of Colin Wilson’s The Books in My Life. How many more books and authors suggest themselves in passing fashion because of their deep importance to me? Robert Pirsig and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Allan Bloom and The Closing of the American Mind. Theodore Roszak and Where the Wasteland Ends. Wise and Fraser’s Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural. Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy. C. S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man. Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes. E. F. Schumacher’s A Guide for the Perplexed. Henri Amiel’s Journal. Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain. Pretty much everything Robert Anton Wilson ever wrote. And on, and on.

So, then, why reject them all and choose Douglas Harding’s The Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth? This takes a minute to hash out.

“Douglas Harding hit upon the key to understanding everything, most especially the ontological place of humanity in the cosmos, in a way that is verifiable by anyone.”

I choose Harding’s massive magnum opus—which offers a philosophical vision and explanation of the whole universe, and thus represents a kind of respectable alternative or counterpoint to the New Agey Urantia book—in part because it intersects at multiple points with my other books, authors, and passions. C. S. Lewis, for example, was so dazzled when a young and unknown Harding sent him the manuscript in 1950 that he ended up writing an enthusiastic preface for the original 1952 edition. “Hang it all,” Lewis said in a reply letter to Harding, “you've made me drunk, roaring drunk as I haven't been on a book (I mean a book of doctrine; imaginative works are another matter) since I first read Bergson during World War I. Who or what are you? How have I lived forty years without my having heard of you before and my sensation is that you have written a book of the highest genius.” Harding later became friends with Alan Watts, a circumstance arising out of their respective positions of prominence in the heady countercultural spiritual stew of 1960s and 1970s Britain and America. Huston Smith spoke approvingly of Harding’s work, and he even wrote the preface to Harding’s classic 1961 book On Having No Head: Zen and the Rediscovery of the Obvious. Crossing over into my horror interests, I introduced Tom Ligotti to Harding’s work circa 2001. Not long after that, the idea of headlessness, clearly inspired by Harding, began showing up in some of Tom’s work.

But again, what about the fact that I haven’t actually read the Hierarchy? This makes for an interesting anecdote in its own right, and it gets to the heart of my choice.

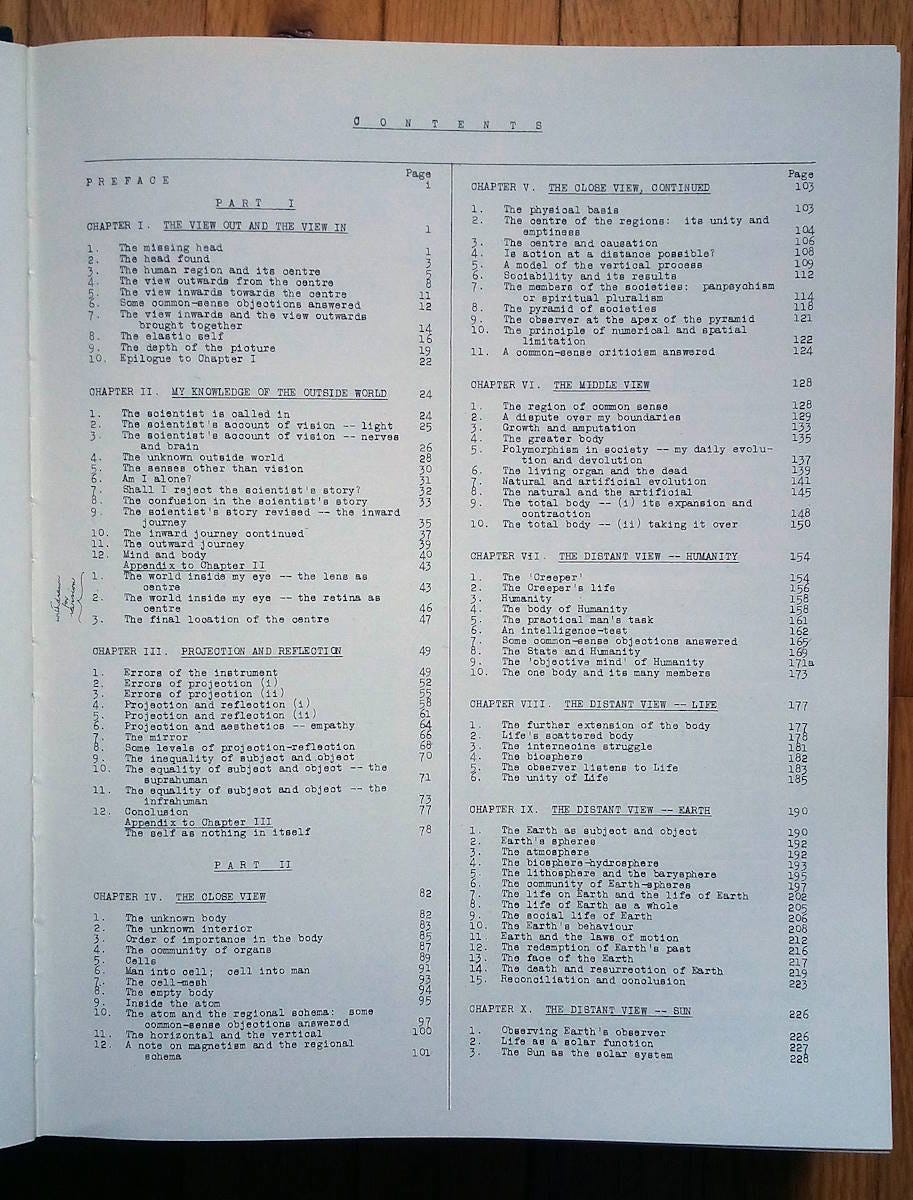

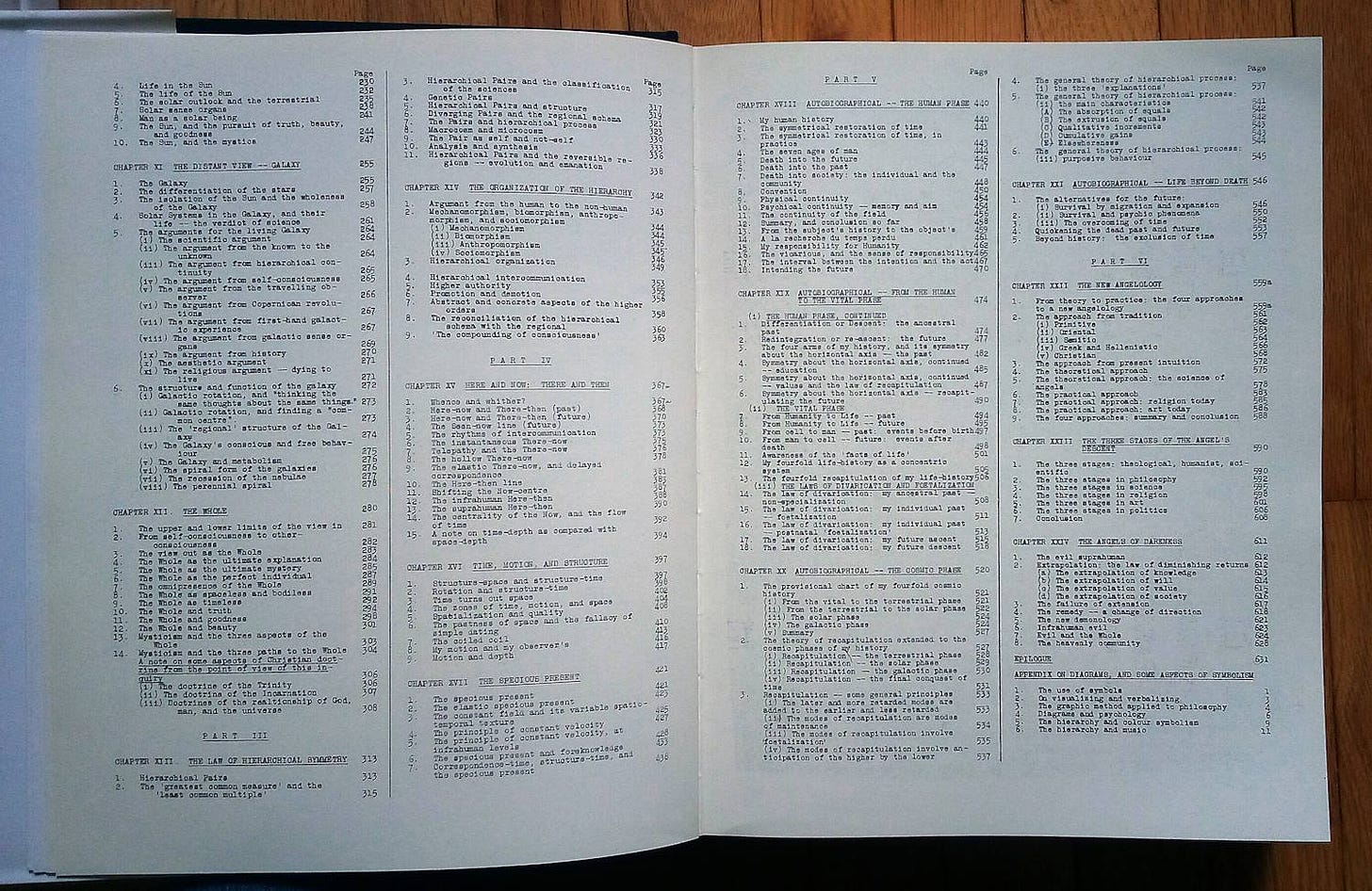

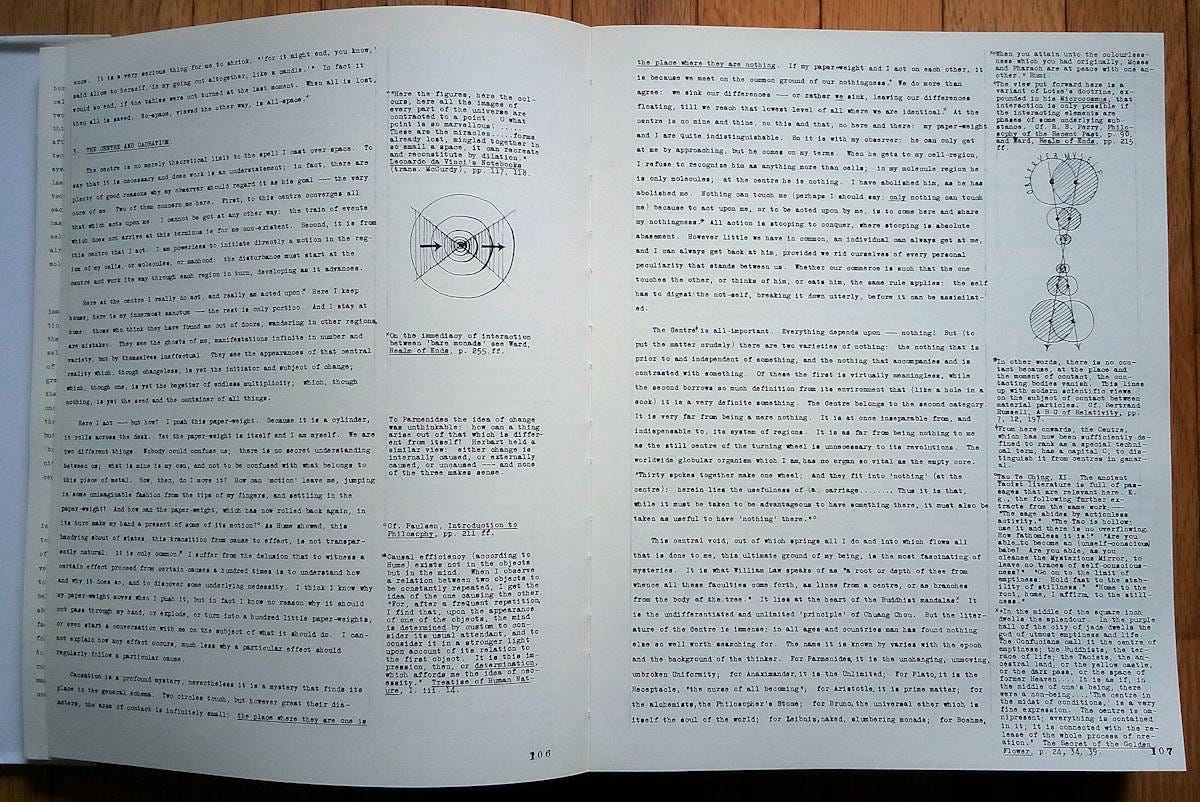

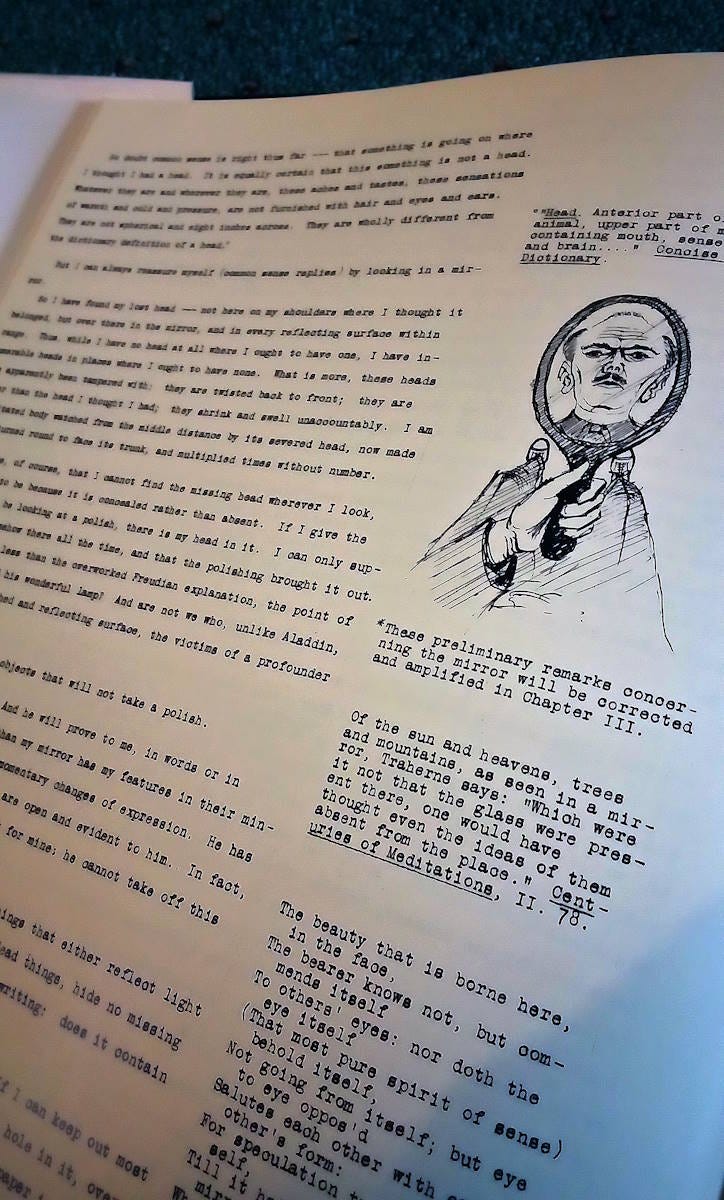

In 1998, Harding’s estate published for the first time the complete version of The Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth. It consisted of facsimiles of the actual pages that Harding typed, wrote, and drew during the eight-year period of inspiration that drove the book’s creation. (Side note: This sustained creative eruption came in the wake of a mountaintop experience in the 1940s when Harding, who had been raised in a rigidly strict and conservative Protestant tradition, suddenly awakened to the vivid, primal, self-evident reality of first-personhood. I have always dug the fact that it was a literal mountaintop experience, not a figurative one; he was hiking in the Himalayas when it happened.) The first edition that was published in 1952 represented a significant abridgement, performed by Harding himself, of that original manuscript. This meant the new, uncut version emerged half a century later as a long-awaited publishing revelation. When I saw it announced and read of its ultra-limited press run, I immediately preordered it and thus became one of only several hundred people on the planet to own a copy—and one signed by the author, no less.

Here are some exterior and interior photos of my copy. The first one gives a sense of just how massive the book is. The little book next to it is a regular-sized paperback edition of Harding’s On Having No Head.

This book has sat almost untouched on my bookshelf ever since the day it arrived. Or rather, it has sat unread on a series of shelves, first in the Missouri Ozarks, then in the Central and West Texas plains, and now in the Boston Mountains of Arkansas. (Yes, I have moved around a bit.) Why this delay, failure, or refusal to read it? For one thing, as shown, it’s a forbiddingly huge object, an outsized tome of nearly 700 pages that weighs a full 10 pounds (a fact that I confirmed a moment ago with a postal scale). This means if I dive in to read it, it will inevitably eat up years of my life, since I know that I will read it slowly and meditatively, as I do with all spiritual books of high value, in order to gain the full effect. So I feel the same hesitation that I would feel before plunging into any long-term engagement.

But more importantly, there’s the almost perverse fact that when it comes right down to it, I prefer to keep the whole thing a mystery. Having read many of Harding’s other writings, I know that he really did hit upon the key to understanding everything, most especially the ontological place of humanity in the cosmos, in a way that is verifiable by anyone. And he made the special contribution of crystallizing this key in the form of an astonishingly straightforward and accessible master concept with accompanying practical applications. This is in contrast to the many other teachers and gurus who state things in a difficult or opaque fashion. Notice, Harding says, that you can never see your own head—that you are actually, in your immediate and instantly verifiable first-person experience, headless. Use this recognition to extrapolate—experientially, not theoretically—the wider truth that as a phenomenological fact, you are not the burdensome, positively existing self that you have always held yourself to be, a vulnerable individual/separate entity that is constantly threatened by danger and want. You are far wider than that. In fact, you are nothing more nor less than pure awareness, pure capacity for experience. You are the space for everything else to happen, the empty arena in which the whole cosmos arises and presents itself. This explains everything, including the doctrines all of the world’s great religions.

In short, Harding boiled down the basic nondual insight into an easily communicable and confirmable proposition, and he stated it far more simply and gracefully than I just did, accompanied by practical exercises for recognizing it in your own experience. This much I know from reading his other work. But in his Hierarchy he laid out the full ramifications for human life, and for the macrocosmic and microcosmic levels of the universe, in overwhelming detail. I have browsed enough in those pages to be thoroughly dazzled.

“I cherish this book—and choose to leave it unread, the better to preserve that creatively fertile interplay of knowledge and mystery.”

And that, in the end—the fact of the book’s profound and expansive interrogation and articulation of reality—is why I prefer to let it all remain sealed up between those giant covers, where it can remain safely sheltered from my gaze, or maybe where my gaze can remain safely sheltered from it. As a writer, musician, and thinker, I’m constantly skirting the boundary between mystery and knowledge. And I find a bottomless reservoir of energy in the tantalizing interplay between the two, especially as they figure into works of supernaturalism and cosmic dread. Harding, I think, really has said what there is to say about the deep knowledge of heaven and earth, not just partially but completely, as a fully formed statement. It can be said in other ways. There are other worthwhile articulations from other writers and traditions. But his is one of the few that states it comprehensively. Therefore, I cherish this book—and choose to leave it unread, the better to preserve that creatively fertile interplay of knowledge and mystery.

So, again: This is the book I would like to be buried with. And I want that to happen without my having plumbed its rich philosophical and spiritual depths.

The very thought of this fills me with a strange warmth. I fondly imagine that enormous, weighty tome lying forever atop my motionless breast in a lightless coffin buried beneath six feet of rich, cool, dark earth. I envision this literary embodiment of intertwined primordial mystery and ultimate knowledge lying heavy and silent above my heart (the seat of the soul) and my lungs (the seat of the spirit). And I imagine a day when it may greet some would-be grave robber with a surprising and suitable coda to the epitaph that I hope he will have first encountered on my headstone, if I end up proving worthy: “He honored the mystery.”

A non-exhaustive list of other writers who were invited to this series includes Thomas Ligotti, Laird Barron, Stephen Graham Jones, Adam Nevill, Mark Morris, Brian Lumley, Mark Samuels, Reggie Oliver, Michael Marshall Smith, Christopher Golden, Simon Strantzas, Quentin S. Crisp, John Langan, and Joel Lane. Good company to be in. The whole series is still available online, btw, at the blog of Matthew F. Riley, who ran the Horror Reanimated blog with fellow writers Joseph D’Lacey and Bill Hussey.

After this read, I have the overwhelming desire to acquire Douglas Harding's 'The Hierarchy of Heaven and Earth'. To read it, yes (my mind thinks), yet I also wonder if just having it reside in my library on a shelf would bring me your level of satisfaction. Well, curiosity may have killed the library's cat, but I'm on my way to purchase it! Thanks for the recommend! 💜🐈📕📖

Harding’s Headless Way practice has become one of the most powerful spiritual experiences of my life. I had no idea about this other book of his. Thank you so much for putting it on my radar.