When Horror Becomes Revelation: Thomas Ligotti’s Special Plan for This World

On metaphysical horror, cosmic pessimism, and the limits of awakening

Dear Living Dark reader,

Today I’m sharing an essay with you about metaphysical horror, cosmic pessimism, and the strange proximity between religious revelation and existential dread. Or more accurately, I’m sharing a portion of something longer. Though it can be read as a stand-alone piece, what follows is excerpted from my essay “A Formless Shade of Divinity,” whose subtitle identifies its wider context: “Chasing Down the Demiurge in Thomas Ligotti’s ‘The Red Tower,’ I Have a Special Plan for This World, and This Degenerate Little Town.”

My involvement in horror fiction and publishing, though it often takes a side seat here at The Living Dark, remains one of the foundations of my writing, my outlook, and my personal and professional history. So does my long involvement in the critical and creative scene surrounding Thomas Ligotti, where I have somehow come to be recognized as one of the major interpretive writers on his work over the past quarter century or so. Long-time TLD readers will remember that Ligotti has come up here several times before.

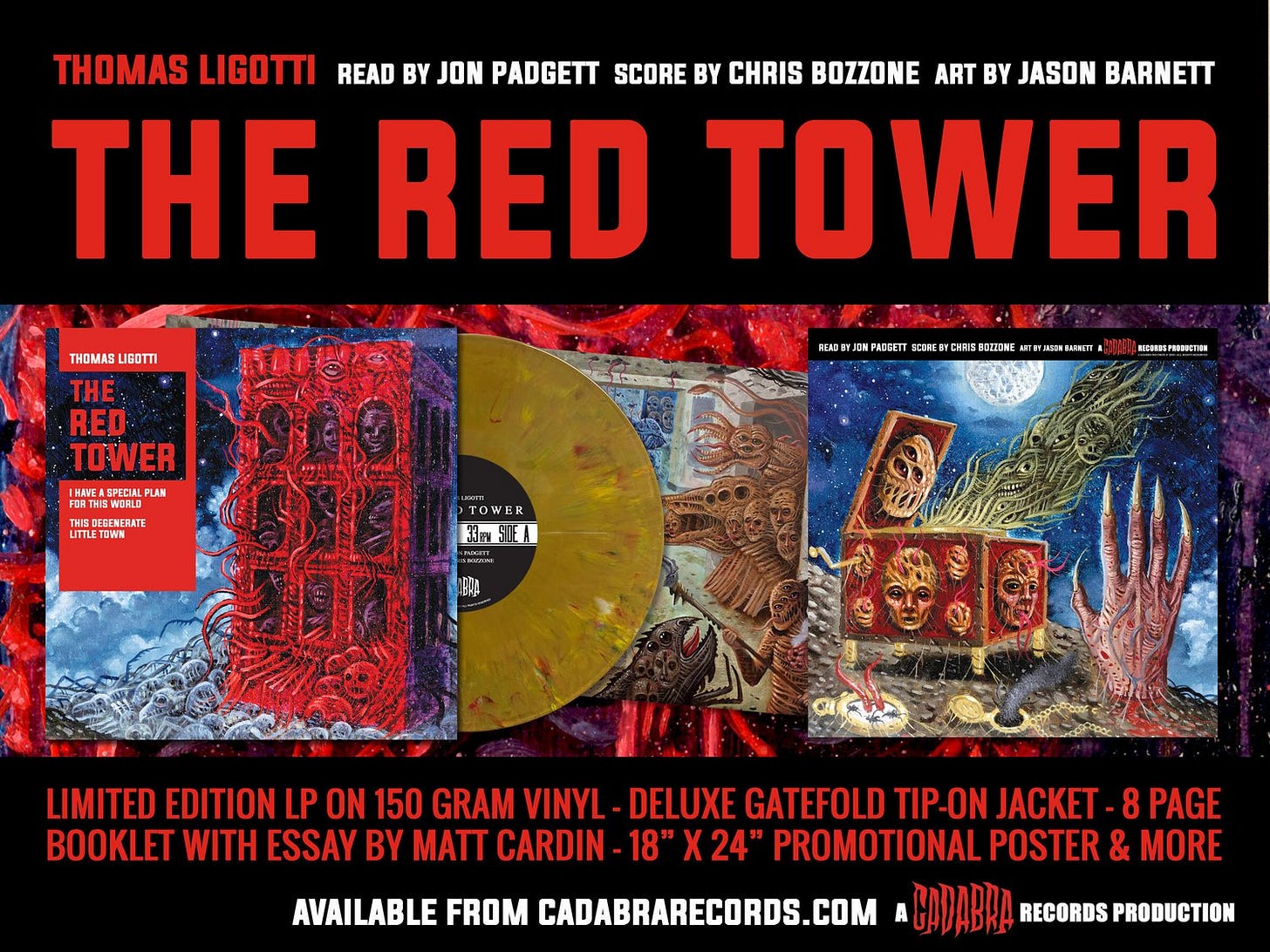

“A Formless Shade of Divinity” first went out into the world in 2020 as a booklet accompanying the vinyl audio recording The Red Tower, produced and published by Cadabra Records. The album presents dramatic readings of the three Ligotti works named in the subtitle—one short story and two poem cycles—featuring my dear friend Jon Padgett as reader, accompanied by a musical score by Chris Bozzone. It marked my second collaboration with Cadabra Records on a Ligotti project; the first was a reading of Ligotti’s “The Bungalow House,” released in 2018 and featuring the same team.

It was a pleasure and honor to be invited to write the essay portions of these releases. The projects were also formative for me in a more inward sense, giving me a formal occasion/provocation to articulate, for myself as much as for anyone else, why certain works by Ligotti had haunted me for years.

The section of “A Formless Shade of Divinity” that I’m sharing with you here is titled “Laughing and Screaming in an Endless Dream.” It’s devoted to exploring and explaining Ligotti’s poem cycle I Have a Special Plan for This World. The excerpt makes up roughly 1700 words of the essay’s total 6,300-word length.

It may help to situate this section within the essay’s wider thesis. My argument is that the three works under consideration present themselves as more than literary horror. In both form and function, they operate as revelatory texts—texts that seek to work a transformation upon the reader, in a manner analogous to religious scriptures. I’ll quote from my own introduction to explain what I mean before proceeding to the excerpt itself:

[U]pon starting to read them, one notices immediately that they present themselves and function as more than, and other than, mere works of horror literature. Much like religious texts, these key entries in Ligotti’s total body of work convey the sense that they are attempting (as it were) to channel directly to the reader the transcendent reality whose existence they posit. Put differently, they attempt to act as windows, and also, in some sense, as textual instantiations or incarnations of the nightmarish reality toward which they gesture. In this, they are transformative texts—again, more like religious scriptures than mere stories that change the reader’s perception of reality. They are texts that work, or try to work, an alteration upon and within the reader’s mind, brain, and perception, and in so doing work a veritable ontological change upon the reader him- or herself. . . .

These texts seek to work a change upon the reader, to open the reader’s mind to a new way of seeing, knowing, and feeling about his or her existence, the cosmic environment in which it plays out, and the foundational ontological reality upon which both of these phenomena, self and cosmos, rest, and from which they derive.

More succinctly, one could say, if one were so inclined, that “The Red Tower,” I Have a Special Plan for This World, and This Degenerate Little Town are not so much literary texts that one reads as revelatory experiences that one risks. They are scriptures of a sort, ostensible carriers of a metaphysical truth that seek to transform those who are “sympathetic organisms” (to quote the monstrous eponymous guru in Ligotti’s short story “Severini”). They speak of a truth—they reveal a truth—the very grasping of which can change the one who grasps.

I trust that my long-standing fascination with the confluence of religion and weird, cosmic, and supernatural horror is evident in this framing. Many of you who make up the Living Dark readership may know my writing more through its engagements with creativity, the daemon muse, nonduality, spiritual awakening, and cultural critique than through my work in the horror field. What follows is one example of how these strands have always occupied the same interior space for me, how metaphysical dread, awakening, and creativity have long stood in a complementary relationship rather than an oppositional one. I hope this speaks to something within you, whether it’s familiar or unfamiliar territory.

As a final introductory note, the complete essay is collected in my book What the Daemon Said, which is available pretty much everywhere.

Warm regards,

Laughing and Screaming in an Endless Dream

On Thomas Ligotti’s I Have a Special Plan for This World

I Have a Special Plan for This World was first published in 2000 in a limited edition of 125 copies by David Tibet’s Durtro Press. Tibet, the founder and long-time beating heart of the British experimental music group Current93, was then and remains now a confirmed fan of Ligotti’s work—Ligotti even chose him to deliver his (Ligotti’s) acceptance speech for the Bram Stoker Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2020—and Special Plan first emerged when Ligotti, who had already written the text, described it to Tibet, who decided he wanted to turn it into a collaborative project. Tibet published the limited-edition book in connection with a compact disc that featured him narrating Ligotti’s text, accompanied by an ominous paramusical landscape and interspersed with deeply distorted vocal effusions. The production also featured audio content from a series of mysterious cassette tapes that Ligotti and his colleagues at Gale Research, the educational publisher where he worked as an associate editor for two decades, used to find lying on a park bench outside the Penobscot Building in Detroit.1

Ligotti’s text takes the form of a series of thirteen surreal poems or “discorporeal prose poems,” all representing, like the text of “The Red Tower,” the darkly unsettling reflections of an unidentified narrator. Dominant themes include the intrinsic and inescapable suffering and despair of mortal, fleshly, embodied life; the dreadfulness of existence itself; the idea of humans as puppets or automatons being controlled by an occult force; the vision of the cosmos as a crummy, creaking, rundown façade that barely conceals a nightmarish horror; and the “special plan” of the title, which seems to have something to do with desiring the unmaking of creation and returning everything to a state of utter non-existence. The exact nature of the plan is never specified, but the narrator hints at it in various ways.

For instance, at the start of the second section, the narrator relates a chance meeting with a shadowy figure—one of many that are encountered in the total dreamscape of the poem cycle—who speaks of having his own special plan. What this figure says indicates that this plan is focused on the idea of annihilating the savage bloody suffering of physical existence and the monstrous drives and appetites that accompany it:

One needs to have a plan, someone said who was turned away into the shadows and who I had believed was sleeping or dead Imagine, he said, all the flesh that is eaten the teeth tearing into it the tongue tasting its savor and the hunger for that taste Now take away that flesh, he said take away the teeth and the tongue take away the taste and the hunger Take away everything as it is— That was my plan, my own special plan for this world

The narrator, however, will have none of that, for his plan, he says, extends far beyond a mere removal of things as they are, reaching all the way backward and inward toward the luminous primal darkness that preceded and precedes all things:

I had heard of such plans, such visions And I knew they did not see far enough— That what was demanded—in the way of a plan— Needed to go beyond tongue and teeth and hunger and flesh Beyond the bones and the very dust of bones and the wind that would come to blow the dust away And so I began to envision a darkness That was long before the dark of night And a strangely shining light That owed nothing to the light of day

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that at one point the narrator characterizes his very own plan as the most horrific thing in the entire horror-filled multiverse, calling it “the worst of all / of this world’s dreams— / My special plan for the laughter and the screams.” And yet, the text is bookended by lines, phrased in incantatory language and repeated verbatim in the first and final sections, that obliquely anticipate a kind of dark bliss that will accompany the plan’s eventual accomplishment:

When everyone you have ever loved is finally gone When everything you have ever wanted is finally done with When all of your nightmares are for a time obscured as by a shining brainless beacon or a blinding eclipse Of the many terrible shapes of this world When you are calm and joyful and, finally, entirely alone Then, in a great new darkness, You will finally execute your special plan

The Hungarian philosopher and social theorist Adam Lovasz observes that I Have a Special Plan for This World is “ironically titled,” in that the text, in its totality, “seeks to express the very absence of such a plan. Ligotti rejects the notion of a cosmic teleology, a divine blueprint that would integrate atomized, separated moments into itself.”

Ligotti’s particular experience of horror might be characterized as the horror of the “deep inside,” the horror to be found at the ontological heart of psyche and reality, whereas Lovecraft’s might be characterized as the horror of the “deep outside,” of the monsters and forces of outer darkness that scratch at the rim of the ordered universe and the walls of conventional human sanity

Interestingly, and perhaps contrastingly, Ligotti derived the title of the piece from the Golberg Mania Questionnaire, a widely used psychological test, developed by the American psychiatrist Ivan Goldberg, that is intended to help diagnose bipolar disorder. One of its questions asks, “Do you have special plans for this world?” Ligotti was apparently so struck by this that he created not just one but two works titled “I Have a Special Plan for This World.” The second, unrelated to the one under consideration here by anything except its title, is a corporate horror story that was first published in My Work Is Not Yet Done (2002).

In any event, buried in the latter half of I Have a Special Plan for This World (the poetic text, not the short story), in section nine, is a set of lines that might validly be thought of as expressing the pure essence of the nightmare ontology that informs and underlies all of Ligotti’s work:

I first learned the facts from a lunatic In a dark and quiet room that smelled of stale time and space There are no people—nothing at all like that— The human phenomenon is but the sum Of densely coiled layers of illusion Each of which winds itself upon the supreme insanity That there are persons of any kind When all there can be is mindless mirrors Laughing and screaming as they parade about in an endless dream

When asked by the narrator, “what it was / That saw itself within those mirrors,” the lunatic “only rocked and smiled / Then he laughed and screamed,” and the narrator reports seeing in his “black and empty eyes . . . as in a mirror,”

A formless shade of divinity In flight from its stale infinity Of time and space and the worst of all of this world’s dreams— My special plan for the laughter and the screams.

In his 2003 book Rational Mysticism: Dispatches from the Border between Science and Spirituality, later released in a new edition with the altered subtitle Spirituality Meets Science in the Search for Enlightenment, the American science writer John Horgan related his personally transformative experience of taking ayahuasca, as well as the subsequent philosophical quest it put him on. He reported that during his psychedelic episode, after experiencing a number of the conventionally predictable DMT-fueled visual phenomena, he found himself “coming face to face with the ultimate origin and destiny of life.” He said he “felt overwhelming, blissful certainty that there is one entity, one consciousness, playing all the parts of this pageant, and there is no end to this creative consciousness, only infinite transformations.”

Then, without warning, the bliss toppled over and inverted itself into an experience of nightmarish terror. Horgan’s description of the nature and source of that terror, and of his vision of the central core of personal and cosmic reality, may shed light on Ligotti’s amorphous divinity and its horrified flight from its own infinitude:

Why? I kept asking. Why creation? Why something rather than nothing? Finally I found myself alone, a disembodied voice in the darkness, asking, Why? And I realized that there would be, could be, no answer, because only I existed; there was nothing, no one, to answer me. I felt overwhelmed by loneliness, and my ecstatic recognition of the improbability—no, impossibility—of existence mutated into horror. I knew there was no reason for me to be. At any moment I might be swallowed up forever by this infinite darkness enveloping me. I might even bring about my own annihilation simply by imagining it. I created this world, and I could end it, forever. Recoiling from this confrontation with my own awful solitude and omnipotence, I felt myself dissolving, fracturing, fleeing back toward otherness, duality, multiplicity.

Horgan went on to say that in the aftermath of this “nightmarish vision,” which he eventually “shaped into a theodicy with gnostic overtones—call it gnosticism light,” he realized that he had come to suspect that “God creates not just for companionship or ‘fun’ but because of His terrified recognition of His own solitude and improbability and even His potential death; God ‘forgets’ Himself and flees into multiplicity because He cannot bear to confront His plight.”

One recalls that Ligotti has told of how he himself experienced a mental-emotional breakdown at the age of seventeen while under the influence of drugs and alcohol, and that this put him in a state of mind that rendered him profoundly receptive to the vision of a bleak, menacing, and monstrous cosmos portrayed in the stories of H. P. Lovecraft, which he discovered soon afterward. Ligotti’s particular experience of horror, though, as he would begin to express it decades later in his own stories, might be characterized as the horror of the “deep inside,” the horror to be found at the ontological heart of psyche and reality, whereas Lovecraft’s might be characterized as the horror of the “deep outside,” of the monsters and forces of outer darkness that scratch at the rim of the ordered universe and the walls of conventional human sanity.2

In I Have a Special Plan for This World, in the image of those “mindless mirrors / Laughing and screaming as they parade about in an endless dream,” and of that “formless shade of divinity” fleeing its own infinite isolation—just like Horgan’s deity, which lives in terror of its own solitude and flees into multiplicity to escape it—Ligotti has provided perhaps the most potent key to articulating his particular vision of the horror at the center of existence.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with a friend. I’d also love to hear your thoughts and comments.

Support This Work

If you want to materially support The Living Dark, you can make a one-time donation or choose a recurring monthly donation. I spend a lot of time tending this project, so I sincerely thank you for even considering it. All posts will always remain free.

Published in December:

“[An] intimate journey into the mystery of creativity and spirit… Cardin weaves practical methods, personal stories, literary references, and mystical insights into a lyrical meditation on what it means to create from the depths of the soul… both deeply personal and universally resonant.”

— BookLife review (Publishers Weekly)“A guide for writers who welcome the dark and hunger for meaning.

— Joanna Penn, author of Writing the Shadow“I can’t think of any [other books] that link the creative act so uniquely or persuasively with spirituality.”

— Victoria Nelson, author of On Writer’s Block and The Secret Life of Puppets“A meditation on the silence and darkness out of which all creative acts emerge....A guide for writers unlike any other.”

— J. F. Martel, author of Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice and co-host of Weird Studies“Important to any writer ready to see through the self illusion and realize the freedom this brings to any creative work.”

— Katrijn van Oudheusden, author of Seeing No Self

Thomas Ligotti, email to author, 6 May 2020. Regarding the specific contents of those tapes, Ligotti has related that they were recordings of “an elderly man reading from various sources, including the local newspaper, the works of Sigmund Freud, and librettos from Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. These readings were often interrupted by mad laughter. Later some of us, including me, saw and heard the guy who was leaving these tapes, which were always placed inside envelopes taken from local banks. . . . On the outside of the envelopes this elderly gentleman, who walked around mumbling and laughing to himself, would write strange phrases, which unfortunately I can’t recall any longer, as well as the source material from which the reading on the tape was taken. Bungalow Bill, a name given to him by David Tibet, would leave these envelopes on benches along the sidewalks in downtown Detroit, securing the envelopes in place with the weight of several pennies. He was a rather distinguished, professorial looking guy . . . and he was most certainly insane” (E. M. Angerhuber and Thomas Wagner. “Disillusionment Can Be Glamorous,” in Matt Cardin, ed., Born to Fear: Interviews with Thomas Ligotti. Subterranean Press, 2014, 62–63). Interestingly, the same tapes also formed the direct inspiration for the recorded “dream monologues” in Ligotti’s “The Bungalow House.”

On the matter of Ligotti’s adolescent mental-emotional breakdown and the vision of horror that it revealed, see my essay “The Master’s Eyes Shining with Secrets: H. P. Lovecraft’s Influence on Thomas Ligotti,” also collected in What the Daemon Said. On the matter of the contrast between Lovecraft’s horror of what is here called the “deep outside” and Ligotti’s of what is here called the “deep inside,” see the same essay.

Loved your book! I'm fascinated by the idea of religion in horror and conversely, horror in religion. Probably goes back to attending Catholic high school whilst simultaneously experiencing the rise of slasher movies.

wow. written squarely within the discomfort. seeing clearly is not salvific but corrosive