Why Ray Bradbury Still Haunts Me

Whispers of October in a Fahrenheit 451 world

Dear Living Dark reader,

Each year when autumn arrives, I’m drawn by a kind of delicate inner gravity to revisit the works of Ray Bradbury, and to recharge his fictional, philosophical, and spiritual vision within me. I suppose that’s because this season with its heightened emotional tone of a bittersweet, energetic delight, mingled with gloom and melancholy, tends to mirror and trigger the feelings that I most closely associate with my lifelong experience of Bradbury’s books.

This effect is intertwined with the transcendent longing that I describe in my essay “Fantasy, Horror, and Infinite Longing” (collected in What the Daemon Said), where I talk about the sense of yearning that has come to me intermittently since childhood, and that often arrives as an adjunct or companion to the autumn season. I speculate in that essay about the profound significance of this yearning for both human consciousness and the fantasy and horror genres, and I talk about some of the authors—C. S. Lewis, H.P. Lovecraft, Colin Wilson—who have known it and directly addressed it in their work. (You can also read my thoughts on this longing in a series of posts that I published years ago at my previous, long-running blog, The Teeming Brain.)

Like the writers named above, Ray Bradbury was a master at both arousing and confirming this same experience of heightened inner intensity. I say this from personal experience. In my youth, my first readings of The October Country, The Illustrated Man, and Something Wicked This Way Comes left a permanent mark on me, both intellectually and emotionally. More than just the sum of their parts, these books conveyed to me then, and continue to convey now, an entire vision of the world in which both darkness and light are intensified to new heights and depths of vividness, and all the daily details of life assume a kind of mythic numinosity that calls forth an intrinsic and inevitable feeling of transcendent longing or sehnsucht. Which is to say that Bradbury’s work exemplifies what I take to be the deep raison d’être of fantasy and horror.

All these qualities account for the fact that I am, in effect, haunted by Ray Bradbury. The ambience of his work and person infuses my life with a sense of longing and delight that is thoroughly distinct, a sui generis effect that I cherish. And I know the same is true for millions of other people—probably including you, since you’re someone who felt drawn to read a post with a title like this one.

Below is a grab bag of impressionistic reflections on the resonance of Bradbury and his work in my life, thought, and affections. I share and dwell on these things as much for my own interest and pleasure as for any interest I think they may hold for you. This is of course the surest way to find mutuality among writers and readers. And I would love to hear your own thoughts and feelings in the comments.

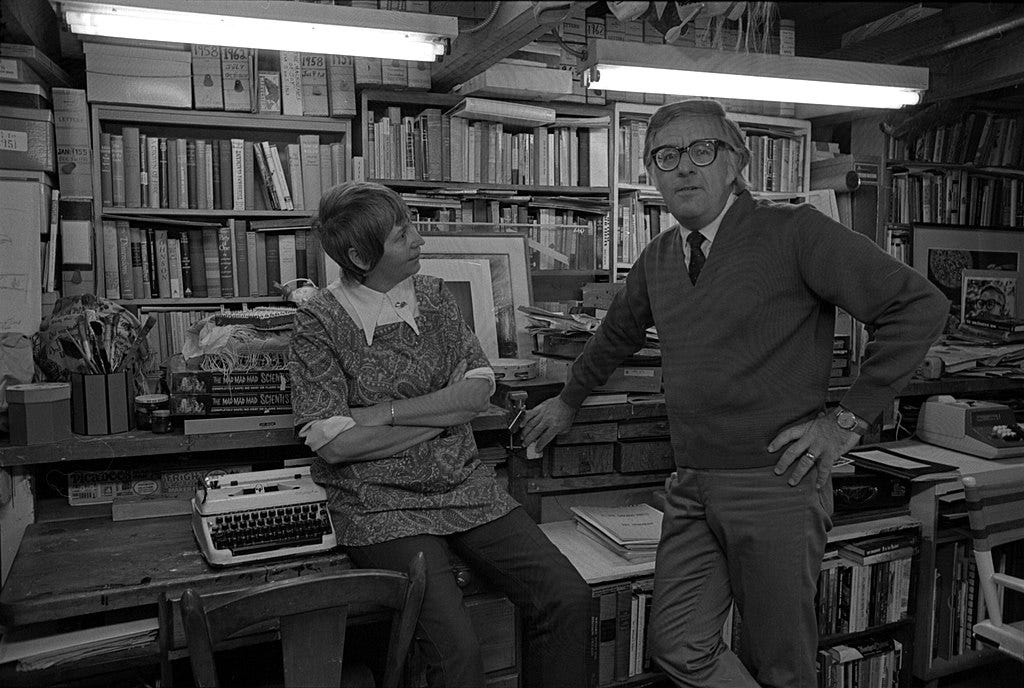

Ray Bradbury was a horror writer

In my 2017 horror encyclopedia, Horror Literature through History, which I edited/created for the academic publisher ABC-CLIO, I included an entry on Bradbury. It was expertly written by Bev Vincent, who’s best known for writing great books on Stephen King, such The Road to the Dark Tower and Stephen King: A Complete Exploration of His Life, Work, and Influences. It was necessary to include an article on Bradbury in a two-volume work that endeavors to provide something resembling a comprehensive overview of (primarily Western) horror literature from the ancient world to the present, because although today Bradbury is best known by reputation as a writer of science fiction, he actually got his start writing horror, and his impact on the field has been significant. As you may know, I, too, got my start as a horror writer. And though I have more commonly cited the influence of Lovecraft, Ligotti, and other select representatives of the weird and cosmic horror tradition, I actually read Bradbury before any of them, at a very tender age. This means his special sensibility for horror entered my psyche long before the likes of Lovecraft, and in fact paved the way and plowed (and fertilized) the field for those later influences.

Bev’s article for the horror encyclopedia described Bradbury’s contributions to horror in some detail. If you’d like to read it, you may be able to find Horror Literature through History at an academic or public library near you. For present purposes, I’d like to share the sidebar that I wrote to accompany the article. It expresses the point in concentrated form—the point again being that Bradbury, in addition to his reputation as a science fiction writer, was a seminal figure for horror:

RAY BRADBURY: HORROR WRITER

Although he is more widely thought of as a science fiction writer—thanks largely to the branding he received as “the world’s greatest living science fiction writer,” an epithet printed on the covers of paperback editions of his books in the 1970s and 1980s—Ray Bradbury is actually better described as a writer of fantasy, and it was often quite dark fantasy, with much of it shading over into genuine horror. His first book, the short fiction collection Dark Carnival, was published in 1947 by Arkham House, which at that point dealt only in supernatural horror. Dark Carnival was later transformed into The October Country (1955), which went on to become a cherished classic among horror readers. In these and many other works, Bradbury made significant and deliberate contributions to horror. He also spoke and wrote passionately, in stories, essays, and public talks, about the necessity of acknowledging and even celebrating, in art, the fearsome, dark, terrifying, and horrifying aspects of life. In a real sense, it would not have been inaccurate during his lifetime to have branded him as one of the greatest living writers of horror fiction.

Bradbury’s biographer, Sam Weller, offers an illuminating summation of the arc of Bradbury’s horror impulse within his overall career, along with a statement of his importance to horror:

Bradbury didn’t return to gothic horror after [1955’s] The October Country, with the exception of his timeless tale of childhood and good and evil, Something Wicked This Way Comes, which was published in 1962, at which point he declared, “I said all I had to say in the field.” But the lasting importance of Dark Carnival and its sibling The October Country show a master short-story writer expanding the boundaries of horror and supernatural fiction. Bradbury may have moved on from these genres, but Dark Carnival and The October Country have a twisted and enduring shadow that continues to captivate and frighten.1

Following on from such things, if you’re searching for some delicious and seasonably appropriate reading to enhance your enjoyment of the current month, I can’t recommend Bradbury’s The October Country and Something Wicked This Way Comes highly enough. And/or you could read one or all of the following short stories:

“Pillar of Fire.” This one was first published in 1948. The synopsis at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database effectively conveys its thrust: “A man who died in 1933 finds himself awakening in 2349 as his grave is being excavated, as all dead people are now being cremated as part of an effort to eliminate any dark or disturbing influences, including the work of Bierce, Poe, Lovecraft, etc.; the rage this generates within him at the loss of an important part of human heritage is the force which animates him as he resolves to create an army of others like him and reverse the trend.” Here’s a PDF of the story as it originally appeared in the pulp magazine Planet Stories:

“The October Game.” Actually, I’m not sure that I recommend this one. Rather, I mention it to illustrate the point that Bradbury truly was a horror writer, and not just in a cozy horror sense. He could legitimately horrify. “The October Game” contains none of the gloomy autumnal magic of Bradbury’s other writings about October and Halloween, nor any of the dark deliciousness of horror in its more traditional aspect like you’ll find in the horror/SF fusion that is “Pillar of Fire.” Like that one, “The October Game” was published in 1948. Unlike that one, this story is utterly grim stuff, dealing with a man who hates his wife and decides to take it out on her in a truly awful way through the medium of their child. It’s probably the darkest thing Bradbury ever wrote, and I still find it kind of shocking that such a story was published nearly 70 years ago (in Weird Tales). Or actually, it might be even more shocking if it were published today, given its theme of child endangerment. Five years after its original publication, in 1953, it received a highly faithful/literal comic book adaptation in an issue of Shock SuspenStories, published by EC, which also gave the world such classic horror comics as Tale from the Crypt and The Vault of Horror. Those were different times, for sure. If you want to read the story, you can find it online, and also its comics adaptation.

“The Thing at the Top of the Stairs.” This one first appeared in Bradbury’s 1988 short story collection, The Toynbee Convector. Drawn directly from Bradbury’s own childhood experience, it tells of a man who returns to his boyhood home, which is now vacant, and remembers how he used to be terrified of the darkness at the top of the stairs, where he was always convinced there was a monster lurking. Now, many years later, as an adult, he discovers he was right. And the thing is still there, waiting for him. Bradbury commented on this story in a 1988 interview for Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air:

GROSS: And it’s about an adult who is very afraid of the dark, as he was as a child. And he’s afraid of walking up a staircase—an unlit staircase. There’s a bulb that he has to turn on at the top of the staircase. And he’s afraid that waiting at the top of the staircase is a monstrous thing. Were you afraid of the dark when you were young?BRADBURY: Yeah, that’s a true story. When I was 4 or 5, 6 years old, we had the bathroom upstairs. And in the middle of the night, when I had to go up there, I had to run halfway up the stairs, turn on the light before I could go the rest of the way. Well, when I was doing this, I’d always say to myself, now, don’t look at the top of the stairs because “it” will be waiting for you. And I never learned not to look. And I would scream and fall back down the stairs, and my mother or father would get up and sigh and say, oh, my God. Here we go again. And they’d turn the light on for me and let me go upstairs.

GROSS: What shape did that “it” have, in your mind?

BRADBURY: I suppose it had a different shape every single night, maybe as the result of my seeing certain horror films that I dearly loved.2

Ray Bradbury was a dystopian visionary

Speaking of horror, have you looked around at the world lately? It seems pretty horrifying in many ways. Maybe this is always true, no matter where you stick a pin in the timeline of human history. And of course horror is in the eye and mind of the beholder—a fact that shows us the secret of transcending it. But still, I think currently we’re all sharing in the sense of collective dread and horror that comes with living through the apocalypse and the kali yuga. And at a time like this, the relevance of Bradbury’s writings not only persists but intensifies. This is because, as many people have noticed, there are multiple ways in which reality seems to have taken a turn straight into the kind of dystopia that Bradbury depicted all the way back in 1953 in Fahrenheit 451, and even earlier that, in his 1951 novella “The Fireman,” which he expanded into F451.

I think maybe the essayist and cartoonist Tim Kreider gave us one of the easiest inroads to grokking this. Two days after Bradbury’s death in 2012 (which I say more about below), The New York Times published an op-ed in which Kreider observed that we have somehow managed to live ourselves into a real-world Bradburyan scenario. I’ll quote his words at some length:

[I]t is worth pausing, on the occasion of Ray Bradbury’s death, to notice how uncannily accurate was his vision of the numb, cruel future we now inhabit…Mr. Bradbury didn’t just extrapolate the evolution of gadgetry; he foresaw how it would stunt and deform our psyches . . . Most of all, Mr. Bradbury knew how the future would feel: louder, faster, stupider, meaner, increasingly inane and violent. Collective cultural amnesia, anhedonia, isolation. The hysterical censoriousness of political correctness. Teenagers killing one another for kicks. Grown-ups reading comic books. A postliterate populace…

[H]is objections were not so much reactionary or political as they were aesthetic. He hated ugliness, noise and vulgarity. He opposed the kind of technology that deadened imagination, the modernity that would trash the past, the kind of intellectualism that tried to centrifuge out awe and beauty…

I think of Ray Bradbury’s work often these days. I remember [his short story] “The Murderer” [about a man who rebels against a frenetic societal nightmare of constant technological distraction] whenever I ask for directions or make a joke to someone who can’t hear me because of her ear buds, when I see two friends standing back-to-back in a crowd yelling “Where are you?” into their phones, or I’m forced to eavesdrop on somebody prattling on Bluetooth in that sanctum sanctorum, the library. I think of Fahrenheit 451 every time I see a TV screen in an elevator or a taxi or a gas pump or over a urinal. When the entire hellish engine of the media seemed geared toward the concerted goal of forcing me to know, against my will, about a product called “Lady Gaga,” I thought: Denham’s Dentifrice [a product advertised ubiquitously in “The Murderer”].3

In applying this reading to our real-world cultural situation, Kreider called for a counter-response that sounds not all that far from Morris Berman’s monastic option—which you have seen me talk about before—with its call for individual acts of resistance, largely internal and attitudinal, that save your own soul while simultaneously preserving and transmitting the seeds of sanity for an eventual new growth of culture on the far side of the apocalypse.

Notably, Berman, too, observed our direct Bradburyan parallels in the book where he first laid out the monastic option, 2000’s The Twilight of America Culture. His words have stayed with me for years:

In 1953, Ray Bradbury published Fahrenheit 451—later made into a movie by Francois Truffaut—which depicts a future society in which intelligence has largely collapsed and the reading of books is forbidden by law. People sit around interacting with screens (referred to as “the family”) and taking tranquilizers. Today, nearly five decades later, isn’t this largely the point at which we have arrived? Do not the data [on the collapse of American intelligence] suggest that most of our neighbors are, in fact, the mindless automatons depicted in Truffaut’s film? True, the story does contain a class of “book people” who hide in the forest and memorize the classics, to pass on to future generations—and this vignette does, in fact, provide a clue as to what just might enable our civilization to eventually recover—but the majority of citizens on the eve of the twenty-first century watch an average of four hours of TV a day, pop Prozac and its derivatives like candy, and perhaps read a Danielle Steel novel once a year…

[T]he society depicted in Fahrenheit 451 has banned books and immerses itself instead in video entertainment, a kind of “electronic Zen,” in which history has been forgotten and only the present moment counts…[The novel] is extraordinarily prescient. Leaving aside the issue of direct censorship of books—rendered unnecessary by McWorld, as it turns out, because most people don’t read anymore—most of the features of this futuristic society are virtually upon us, or perhaps no more than twenty years away.4

Berman devoted much of his book to defining and laying out the monastic approach that he recommended as a viable and helpful response to such a world. I engage with this and apply it to the matter of creativity and spirituality in the conclusion to my new (and currently unpublished) book, Writing at the Wellspring. But I think it is perhaps Kreider, in his New York Times piece, who describes the briefest and most simple approach to understanding and enacting the monastic option in a world like this:

It is thanks to Ray Bradbury that I understand this world I grew into for what it is: a dystopian future. And it is thanks to him that we know how to conduct ourselves in such a world: arm yourself with books. Assassinate your television. Go for walks, and talk with your neighbors. Cherish beauty; defend it with your life. Become a Martian.

Ray Bradbury was a utopian visionary

Fascinatingly, in addition to writing some of the most compelling dystopian fiction—not just in Fahrenheit 451 but in short stories like “The Pedestrian,” “Usher II,” and “The Veldt”—Bradbury also beamed forth an optimistic vision of the human, planetary, and even cosmic prospect that was equally compelling. He was, for instance, a friend of Walt Disney, and he shared Disney’s enthusiasm for the vision of a bright future that’s embodied in such phenomena as Tomorrowland and EPCOT Center. Bradbury actually participated in the conception and design of Spaceship Earth, the iconic geodesic dome at EPCOT that houses both a ride and an exhibit focused on the history of human communication, and that is infused with a decidedly optimistic tone about the future. In fact, he wrote the original script and storyline for the ride.

He also wrote essays on things like the humane design of cities and the possible ways of building and celebrating a positive future for us all. Some of these were brought together in his essay collection Yestermorrow: Obvious Answers to Impossible Questions, which the publisher described as follows: “The visionary science fiction author of Fahrenheit 451 shares his imaginative visions of the future in this collection of musings and memoirs. Combining a series of recollections alongside his personal contemplation about the future, protean master of storytelling Ray Bradbury outlines his thoughts on the state of the world—how the past and present are reflected in society, technology, art, literature, and popular culture—as well as the need for creative thinkers to be the architects of the future.”

For me, the attitude expressed by that book jacket copy was most effectively presented not in one of Bradbury’s essays but in the title story of his aforementioned 1988 short fiction collection, The Toynbee Convector. It tells of a man named Craig Bennett Stiles, who claims to have traveled one hundred years into the future in a time machine that he built with his own hands. He returned with vivid descriptions of a utopian society where humanity had solved its problems and achieved a harmonious existence with technology and nature. His account was so compelling and detailed that it inspired the people of his disillusioned and stagnant society to go out and work hard to make his described future a reality. Decades later, in 2059, a journalist seeks out the aging Stiles, now a recluse living amidst the very utopia he inspired. The journalist, however, discovers a shocking truth: The Toynbee Convector, Stiles’s supposed time machine, is nothing more than a hollow prop. Stiles confesses that he never actually journeyed to the future. Instead, he fabricated the entire experience, driven by a desperate need to rouse humanity from its apathy and self-destruction.

Here are some of the words Bradbury puts into Stiles’s mouth, as spoken to the journalist. I think we can safely assume these are Bradbury’s own thoughts, channeled through one of his characters:

I was raised in a time…when people had stopped believing in themselves. I saw that disbelief, the reason that no longer gave itself reasons to survive, and was moved, depressed and angered by it…Everywhere was professional despair, intellectual ennui, political cynicism…The impossibility of change was the vogue…Bombarded by dark chaff and no bright seed, what sort of harvest was there for man in the latter part of the incredible twentieth century? Forgotten was the moon, forgotten the red landscapes of Mars, the great eye of Jupiter, the stunning rings of Saturn…

Stiles goes on to explain the deep reason for his epic ruse, arguing that optimism, even if it’s technically unwarranted in light of objective conditions, is the best and noblest approach to life, since it has always been through aggressive, intelligent, inspired self-deception that we have advanced and built a better world:

Life has always been lying to ourselves…[T]o gently lie and prove the lie true. To weave dreams and put brains and ideas and flesh and the truly real beneath the dreams. Everything, finally, is a promise. What seems a lie is a ramshackle need, wishing to be born.

Thus did a mid-late career Bradbury use a science fiction story to express his rejection of entrenched pessimism and cynicism.

When he died, his friend and fellow science fiction writer David Brin wrote a tribute for Slate that observed the striking dichotomy in Bradbury’s sensibility, his native attraction to both the darkness of dystopia and the light of hope. Yes, said Brin, Bradbury often “plunged fearlessly into dark, foreboding themes.” But this was only to illuminate the shadows, as Bradbury “saw optimistic progress and dark fantasy as partners, not opposites.” Brin described Bradbury’s forceful rejection of pessimism in memorable terms:

Onstage, Ray Bradbury could wax eloquently and vociferously angry at one thing, at one human trait—cynicism. The lazy habit of relishing gloom. The sarcastic playground sneer that used to wound him, and all other bright kids, punishing them for believing, fervently, in a better tomorrow.

Ray had one word for it. Treason. Against a world and humanity that has improved, prodigiously, inarguably, fantastically more than any other generation ever improved, and not just with technological wonders, but in ethics and behavior, at last taking so many nasty habits that our ancestors took for granted—like racism or sexism or class prejudice—and, if not eliminating them, then at least putting them in ill repute.5

Brin’s tribute was titled simply “Ray Bradbury, American Optimist.”

I still find it fascinating and moving to contemplate this double aspect of Bradbury’s work and character, which came even more to the fore as he aged. And I wish he were here today to observe what’s going on, the metastasizing cancer of societal division, political rancor, and doomsday rhetoric, so that he could speak to it in his inimitable way.

Ray Bradbury was the iconic mentor I never met

But alas, it’s now a dozen years since his death. I was stunned on June 6, 2012, when news of it broke. Yes, he was a very old man who had suffered from declining health for many years. But that was immaterial to my emotional reaction. When I saw the first headline about his passing creep into my social media feeds, I felt almost literally thunderstruck. Then came the flood of additional media coverage. Write-ups rapidly appeared in The New York Times, USA Today, CBS News, The Washington Post, Forbes, and the Guardian. In celebration of Bradbury’s life and legacy, John Scalzi went and made his introduction to the Subterranean Press edition of The Martian Chronicles freely available online (see “Meeting the Wizard). The New Yorker gave free access to Bradbury’s contribution to its recent science fiction issue, an essay titled “Take Me Home.” President Obama issued a official statement from The White House, saying,

For many Americans, the news of Ray Bradbury's death immediately brought to mind images from his work, imprinted in our minds, often from a young age. His gift for storytelling reshaped our culture and expanded our world. But Ray also understood that our imaginations could be used as a tool for better understanding, a vehicle for change, and an expression of our most cherished values. There is no doubt that Ray will continue to inspire many more generations with his writing, and our thoughts and prayers are with his family and friends.6

Until that day, I had literally never known a world without Ray Bradbury. He had been a constant, looming, inspiring presence in my life ever since I first learned how to read. My English teacher during all of sixth, seventh, and eighth grades, a wonderful woman named Mrs. Divine—who still occupies an iconic position in my psyche because of her serious encouragement of my early, inbuilt desire to become a writer—felt it necessary to bar me for a time from checking out Bradbury’s S Is for Space from her classroom bookshelf because, as she saw it, my incessant rereading of it was hindering my literary growth. Later, when I graduated from her classes, she presented it to me as a gift. Even now it sits here in my house, on my bookshelf, surrounded by other Bradbury titles and bearing Mrs. Divine’s inscription to me inside the front cover.

A bit later, The Martian Chronicles, A Medicine for Melancholy, The Golden Apples of the Sun, and, especially, Fahrenheit 451 consumed my affections. I also devoured the Martian Chronicles TV miniseries, the Something Wicked movie, and every episode of Ray Bradbury Theater. Later, when I was in college, François Truffaut’s cinematic adaptation of Fahrenheit 451 entered my top-ten list of most beloved films. A few years later, Bradbury’s collection of essays about creativity and inspiration, Zen in the Art of Writing, became one of my touchstone texts on the subject, deeply influencing my developing understanding and experience of the daemonic muse.

So this is all to say that when Bradbury died, I lost someone very dear to me, someone who felt like a close friend even though I had never met or communicated with him. It was always a great comfort to know that a writer whose work was so important to me was still there, still alive, still a living, breathing, flesh-and-blood presence. I never got to enjoy that with most of my other most cherished influences, such as Lovecraft, who died 33 years before my birth, or Alan Watts, who died when I wasn’t yet three years old. Most of my dearly beloved authors have always been passed-on presences, people whose words, minds, and spirits have interacted with me from beyond the grave (although I’m lucky enough to be walking the earth contemporaneously with Thomas Ligotti). But Bradbury was right there, standing psychically nearby, emitting waves of fiery vitality.

Or at least that’s how it was until that day in June, a dozen years ago, when we heard to our dismay that we were all going to have to learn to live in a world without him.

What we still have, of course, are our memories and his books, plus his wider legacy, extending throughout movies, television, and every other form of media and entertainment. And that’s the thing about books, isn’t it? Even when their authors depart, the books remain as repositories of their inner lives and personal visions. Uncle Ray’s books are still here with us. So is his mythic presence, threading its way through our collective culture and psyche.

Often when I think of him, I think of the wonderful line with which Playboy wisely chose to end its classic 1996 interview with him:

Playboy: Do you think our souls live on or do we cease to exist when we die?

Bradbury: Well. I have four daughters and eight grandchildren. My soul lives on in them. That’s immortality. That’s the only immortality I care about.

I also think of his evocative lines at the start of The October Country, which are all that’s needed for recharging the blessed Autumnal Vision in a bleak Fahrenheit 451 world:

October Country…that country where it is always turning late in the year. That country where the hills are fog and the rivers are mist; where noons go quickly, dusks and twilights linger, and midnights stay. That country composed in the main of cellars, sub-cellars, coal-bins, closets, attics, and pantries faced away from the sun. That country whose people are autumn people, thinking only autumn thoughts. Whose people passing at night on the empty walks sound like rain.

Warm regards,

Books mentioned in this post:

By Ray Bradbury

Yestermorrow: Obvious Answers to Impossible Questions

By other writers:

Horror Literature through History: An Encyclopedia of the Stories That Speak to Our Deepest Fears (Matt Cardin)

What the Daemon Said: Essays on Horror Fiction, Film, and Philosophy (Matt Cardin)

The Road to the Dark Tower (Bev Vincent)

Stephen King: A Complete Exploration of His Life, Work, and Influences (Bev Vincent)

The Twilight of American Culture (Morris Berman)

NOTE: I’m an affiliate of Bookshop.org, which helps local, independent bookstores thrive in the age of ecommerce. I’ll earn a commission if you click through one of the affiliate book links in this post and make a purchase.

Sam Weller, “Where the Hills Are Fog and the Rivers Are Mist,” The Paris Review, October 26, 2015.

“Ray Bradbury: ‘It’s Lack that Gives Us Inspiration,’” NPR, June 8, 2012.

Tim Kreider, “Uncle Ray’s Dystopia,” The New York Times, June 8, 2012.

Morris Berman, The Twilight of American Culture (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000), 42, 96

David Brin, “Ray Bradbury, American Optimist,” Slate, June 6, 2012.

David Compton, “President Obama on Ray Bradbury,” June 6, 2012.

He's one of my many mentors I never met, as well....

Every word Ray Bradbury ever wrote in his books is haunting, always leaving something to think about. This essay is such a great reminder of all his great work!