The Time John Astin Explained Christmas to Me

Dickens, a Buddhist Scrooge, and the universal spirit of Christmas

Dear Living Dark reader,

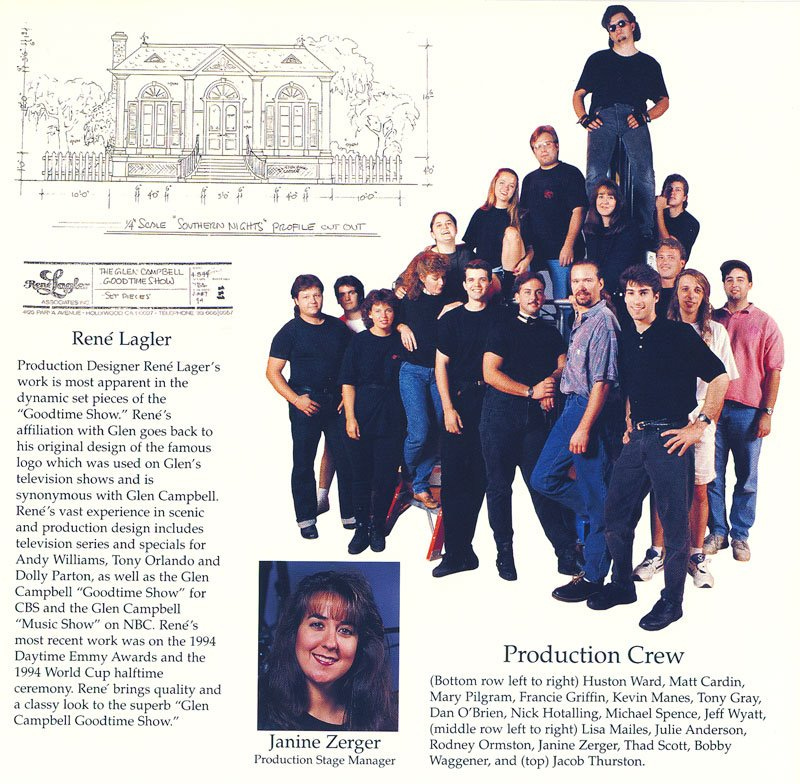

Three decades ago, in the mid-1990s, when I was only a few years out of college and just starting on my professional path, I was gifted with a Christmas-related experience that had never occupied a square on my work-and-career bingo card. It came about in connection with the fact that life in the wake of college graduation had led me to Branson, Missouri, and to The Glen Campbell Goodtime Theater, where for two years I worked as Glen’s live video director. And it involved a personal encounter with an actor whose memorable presence had wound its way through many of the movies and television shows that populated my movie-and-TV-saturated childhood. It also involved Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, a book and a story that had been dear to me from an early age. All these things came together to result in that actor saying something to me that remains, to this day, one of the most insightful and delightful things I ever heard anyone say about the universal spiritual appeal of Dickens’s classic story.

It actually took place at the very end of my time in Branson. Here’s what happened:

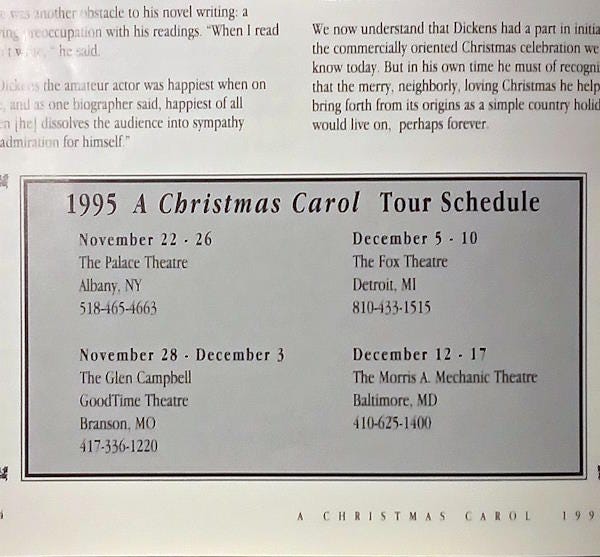

In December 1995, the last thing I ever did at Glen’s theater before leaving to start work in February as a video and media producer for Missouri State University was to participate in a touring musical production of A Christmas Carol. This production arrived in Branson and landed at Glen’s theater for a week-long run, and it gave those of us on the theater crew an enjoyable opportunity to do something different from our normal duties. The theater’s owners (not Glen but a show business company) allowed the play to use us as stagehands. So this meant that, after a quick group meeting with the show’s costume director, we were fitted with properly nineteenth-century-looking Dickensian costuming and placed onstage to move around stage flats for scene changes during the performances. My normal work at the theater involved directing a camera crew to produce the live video portion of Glen’s twice-daily shows that played on the IMAG (image magnification) screens above the stage. So this change-up represented a novel and fascinating departure from that.

Beyond the novelty value, one of the most fascinating parts of the whole thing was the identity of the actor filling the lead role of Ebenezer Scrooge. As I was astonished to learn in the weeks ahead of the show’s arrival, Scrooge would be played by none other than John Astin. I do not, of course, mean the current spiritual writer/teacher John Astin (whose work I heartily recommend). I mean the Hollywood John Astin, the actor who had played Gomez Addams in the old Addams Family TV series, and who would in 1996 play the character of The Judge in Peter Jackson’s The Frighteners, and who had appeared in everything from West Side Story and National Lampoon’s European Vacation to the original Twilight Zone and Night Gallery. The actor whose son, Sean Astin, had already starred in The Goonies and Encino Man and Rudy, and who would go on to play Samwise Gamgee in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings. As I learned from theaterwide scuttlebutt, it turned out that Astin had succeeded Wilford Brimley—another huge name from the entertainment world of my youth—in the role of Scrooge after Brimley had toured with the same drama company a couple of years earlier.

My time in Branson had already seen me working with or around multiple celebrities, including Kenny Rogers, Barbara Mandrell, Vince Gill, Billy Ray Cyrus, Garth Brooks, and even many stars from outside the show business industry’s country music wing, such as Gladys Knight, the Everly Brothers, the Smothers Brothers, and Doc Severinsen. But John Astin was the first celebrity actor to enter that milieu (unless you count Kenny Rogers with his multiple television movie appearances, or maybe Glen himself with his famous turn opposite John Wayne in 1969’s True Grit). Twenty-five-year-old me was fairly starstruck by the mere thought of it, long before the troupe arrived. But I didn’t know if I would actually get a chance to meet him or talk with him. You learn pretty quickly when you work in show business that being near celebrities and performers on a production (“the talent,” as crew members sometimes call them) doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll have real contact with them. Lines of professional decorum and sheer practical workaday necessity often preclude that.

But in this case, it turned out that such an opportunity did arise. Through sheer luck, the piece of stage scenery that I was responsible for handling was one that Mr. Astin ducked behind and then stayed behind for a few minutes at a key point in the play. This meant we were there beside each for a few minutes out of each performance, alone in the shadows together, while the scene went on, until his cue came to reemerge. I remember standing there the first time it happened—pretty much every time it happened—feeling amazed that he was really there, a real-live presence stepped off the movie and television screens that had surrounded me all my life, though in his old-fashioned Scrooge dressing gown and nightcap, and sans the famous mustache, he looked nothing at all like Gomez Addams or any of the other characters I had seen him play.

There was of course no opening there for me to talk to him, to introduce myself, to have some kind of personal interaction. We were hiding behind a piece of scenery during a live play, after all. The most we could do was acknowledge each other with brief glances, which we did, while I silently marveled at how life had led me to such a strange and unexpected experience.

But then, on maybe the third or fourth night of the play’s six-day schedule, a chance did arise for me to speak with him. Or rather, I manufactured it. Specifically, I took advantage of Mr. Astin’s practice of taking up a spot at an autographing window on the floor next to the stage after each show, where he greeted the audience members as they came streaming past on their way to the exit. He did this while still dressed in full Scrooge regalia, and he appeared to enjoy it immensely, though in a kind of quietly half-shy way that I found intriguing. I remember watching this after the first day’s performance and finding it interesting. Then at some point during the next couple of days, I realized it could serve as my opportunity.

At this point I should pause to mention that A Christmas Carol is one of my favorite novels. I first read it as a teenager and then, in my twenties and thirties, made a ritual practice of rereading it every December. I have watched and rewatched a dozen or more of its movie and TV adaptations, with the 1984 version starring George C. Scott standing as my favorite, and with 1970’s Scrooge, starring Albert Finney, remaining a close second. For six years in the early 2000s, when I worked as a high school English teacher, I taught the novel to my students each December. So this is all to say that Dickens’s classic Christmas ghost story of a cruel-hearted miser’s redemption has occupied an important place in my affections for many years, and that this was already the case back in 1995 when that play came to Branson. In fact, on the night when I maneuvered to speak with Mr. Astin after the show, I was already engaged, outside the theater, in my annual Christmas Carol reread.

When the evening’s performance had ended and the audience members were queuing up to file past him at the window, I positioned myself last in line, thus creating an opportunity to meet him formally and, I hoped, discuss the play and the novel with him. The line moved rapidly that night, so almost before I knew it, the crowd had dwindled down and tapered off, and there I was, face-to-face with John Astin at the autograph window, with the two of us relatively alone in the theater except for the various crew members who were attending to their post-show duties. I think I also remember that someone else, maybe his manager, remained as a quiet and unobtrusive presence behind him. In any case, a sudden realization came to me: that I felt distinctly nervous.

As I recall, I did the whole throat-clearing thing and introduced myself. He smiled that little smile and nodded. His eyes beneath the bushy-white Scrooge eyebrows were sharp and alert. Following the general script that I had mentally prepared, I told him how much I appreciated his performance as Scrooge, which was charming. As planned, I also took advantage of the extra time afforded by the absence of anybody behind me to tell him how much A Christmas Carol meant to me. I told him about my habit of rereading the novel each year, and I said the story’s spiritual message touched me deeply.

He listened thoughtfully, nodding. Then he replied by saying something about the spiritual core of A Christmas Carol. And it was far more than what I had allowed myself to hope for. In fact, what he said has continued to resonate and provide meaning for me down through the years, all the way to the present.

I would summarize his words for you, but as it turns out, I don’t have to. In preparing to write this reminiscence, I did some online digging to see if there might be any information available to confirm and revive these memories. The answer was yes. In particular, I located a 1995 newspaper article from Baltimore—the last of the touring play’s four stops—and found that, a week or so after leaving Branson, Mr. Astin said the same thing to the reporter there that he said to me at the autograph window. In fact, he laid it out in more detail. This means I don’t have to rely on my memory alone to recall it.

Here is the relevant passage from that article. Mr. Astin’s words in it are a direct echo of what he told me personally on a dark December evening three decades ago in Glen Campbell’s theater in Branson, Missouri, in the wake of his performance as Scrooge. At the time, I didn’t know I would be carrying his words with me for the next thirty years:

Until he took on the role of Scrooge last year, Mr. Astin was probably one of the few actors to have never performed in an adaptation of the Dickens classic. “Not even in grade school,” he says in a Gomez-like aside, using a tone of voice that can’t help but have an exclamation mark at the end of every sentence.

Still, he’s hardly new to the story. What human being is? And he has some thoughts on what has made “A Christmas Carol” the holiday staple it is.

“I don’t think there is anything in this story to turn off anyone,” he says. “The message is universal, absolutely pure — that life itself is extremely important, that the dignity of every individual human life must be acknowledged, must be understood, if we are to experience true happiness. The implication of this story is that no one is a hopeless case, not any of us. Dickens takes this seemingly irredeemable character in Scrooge and allows us to see how he is transformed virtually overnight.”

Plus, he adds, the story’s appeal “is universal. Though it is nominally [a Christian story], it is really something that’s acceptable to virtually every religion. I don’t think it’s restricted at all in that way.”1

These cogent observations on the universal spiritual appeal of A Christmas Carol ring with extra depth or resonance when you bear in mind that the man who spoke them is a Buddhist. In fact, John Astin has long been one of the more prominent practicing Buddhists in American show business. I first learned of this myself all those years ago in Branson, ahead of the theater troupe’s arrival, when I was told that he had requested vegetarian meals from the local caterers. Curious, I asked someone about the reason for this request, and I was told that he was a Buddhist. I pictured Gomez Addams in my mind’s eye and tried to square that image with my stereotypical image of what Buddhists were like. It didn’t quite work. Nevertheless, the intel was correct: John Astin was a Buddhist.2 As it happened, he also turned out to be someone with an unusually deep understanding of one of the world’s great novels, written in a Christian context, about human redemption.

Back to the encounter in Branson: I recall that after he said what he said to me, I voiced my agreement. I also added that it seemed to me the very depth of Scrooge’s descent toward a condition that some might consider irredeemable accounted for the dramatic nature of his redemption when it finally occurred. In other words, he only “snapped back” with such shocking force and exuberance because of the sheer depth of his fall. Mr. Astin nodded, appearing pleased. Today, I can still vividly remember how strange, in an almost giddy way, it felt to be standing there in that particular environment, having that particular conversation with that particular person.

To cap this off: At the play’s next performance on the following evening, when the moment came for Scrooge to leave the scene temporarily and hide behind the piece of scenery that I had moved into position, Mr. Astin took his place back there beside me in the shadows as usual. But this time, he paused to look directly at me for a sustained moment. He gave me a warm little smile and a nod of silent greeting. I nodded in return, feeling a warm glow. And then the show went on.

Warm regards,

Chris Kaltenbach, “Tickled to Death Scrooge: Far from despising Gomez Addams as the character who pigeonholed him, John Astin is thankful for that ghost of TV seasons past,” The Baltimore Sun, December 11, 1995.

More specifically, he practices Nichiren Buddhism, a branch of Mahayana Buddhism that has attracted quite a few celebrity followers, including Patrick Swayze, Tina Turner, Herbie Hancock, Orlando Bloom, and Chow Yun-Fat.

Matt, it was particularly moving for me to read this account as John Astin, the actor, is actually my Uncle John (my Dad's younger brother). I would be very happy to share your beautiful post with him as I think he would be touched to read it.

Loved this, Matt, and hopefully the internet is correct, and John Astin is still with us at 94. Bless his dear, aged heart. Btw, you look about 16 yrs old in that crew photo. 😸