The Task Enjoined by Heaven

A non-poem by a non-poet, with reflections on Mary Shelley's 'Frankenstein'

As my longtime readers will already know, there is no poet in me, at least as judged by the plain fact that I have never produced a single line of poetry aside from a few wretched verses that I wrote under duress for English class assignments during my adolescence. Still, this thing (the thing below) recently, somehow, happened. So I thought I would share it with you. I honestly can’t explain where it came from. All I can tell you is that the circumstances of its origin involved an early morning freewriting session in a kind of creative trance. When I looked back at the text on the page, I realized a portion of it was essentially a poem that would reveal itself as such if rearranged into poetic lines. And since the mystery of creativity is one of the guiding themes here at Living into the Dark, I figured I would share the result with you.

The Task Enjoined by Heaven

There is a voice

Sometimes loud, sometimes soft

It does not care if I hear it

There is a path

Sometimes clear, sometimes not

It does not care if I keep it

There is a flow

Sometimes swift, sometimes slow

It does not care if I feel it

There is a source

Sometimes near, sometimes far

It does not care if I know it

But hearing, keeping, feeling, knowing—

These are all that matter

The title listed above had already suggested itself when it occurred to me to look up the phrase “task enjoined by heaven.” Any latent sense of a potential daemonic muse involvement in the unexpected appearance of those poetic lines in my unlikely mind was confirmed when I found that the only exact match for this phrase, or at least the only readily locatable one, occurs in the following sentence:

I pursued my path towards the destruction of the dæmon, more as a task enjoined by heaven, as the mechanical impulse of some power of which I was unconscious, than as the ardent desire of my soul.

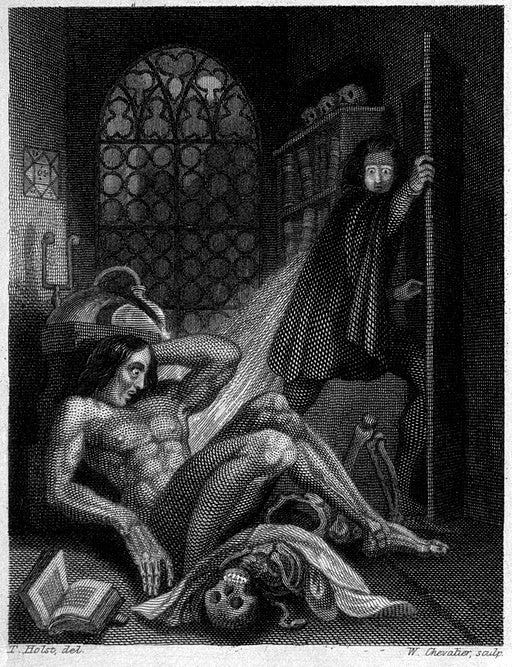

The source is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, both the original 1818 edition and the revised 1831 edition. The line occurs very late in the novel, in fact in the last chapter of Victor’s portion of the nested narrative, and it expresses his attitude toward the revenge-fueled pursuit of his monster across the European continent and toward the Arctic Circle that occupies his final months. During this journey he becomes increasingly unmoored from rational consciousness. He feels himself to be surrounded and sustained by benevolent spirits, and he convinces himself that waking and dream reality have transposed themselves, so that his daytime pursuit of the monster is a dream, whereas the blissful nocturnal reunions with his dead loved ones (murdered by the monster) that he experiences in dreams represent the real world.

Ms. Shelley’s novel has been deeply meaningful to me over the years. I first read it in the autumn after my college graduation, when I was experiencing significant psychological turmoil. This meant the emotional agonies endured by both Victor and his wretched creation struck me with an almost preternaturally vivid sense of identification and significance. A few years later I took an entire graduate class devoted to Frankenstein and its many literary and philosophical backgrounds and influences, including not only the heady tradition of Gothic novels and ghost stories but the rich trove of additional texts and ideas that young Mary channeled into her hideous progeny, including the ideas about education and human consciousness advanced by her father, William Godwin, and by Rousseau; the alchemical texts and teachings of Cornelius Agrippa and his ilk; and the three books — Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther, Plutarch’s Lives, and Milton’s Paradise Lost — that give the unhappy monster his education when he stumbles across them in a forest. Then I ended up teaching the novel to high school sophomores for six years, resulting in the fact that I can now boast that I have literally read Frankenstein cover-to-cover 21 times, 15 of them out loud (with the help and participation of my students). My essay on Frankenstein as a kind of parable about the destructive alienation of the visionary creative unconscious from the rational mind under the sway of a scientistic monomania, which appears in my What the Daemon Said, expresses some of my deep interests in the story. The upshot is that the archetypal myth of Victor Frankenstein and his monster is imprinted deeply upon my life path and my philosophical-spiritual sense of things.

Victor’s monster is the very incarnation of his spiritual double, his literalized, externalized daemon. Because he does not embrace and honor it, they are both destroyed.

One aspect of the story’s multilayered meanings that has always foregrounded itself to me is its rich metaphorical illustration of the potential dangers and difficulties of the creative process. Victor is driven to his act of creation by a ferocious unconscious impulse that he cannot deny. The actual process he employs is both technical and magical, involving a heady combination of scientific knowledge, skills, and ambitions with visionary and alchemical ones. The end result is likewise as independent and autonomous as the impulse that gave rise to it, representing, in this particular case, not so much a material-mechanical flesh monster as the very incarnation of Victor’s spiritual double, his literalized, externalized daemon. Because he does not embrace and honor it, they are both destroyed.

“If you bring forth what is within you,” says one popular translation of saying 70 in the Gospel of Thomas, “what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what is within you will destroy you.” In an interesting variation on the combined promise and warning of this ancient wisdom, Victor brought forth what was within him, but it destroyed them both, because he found himself unable to own or accept it.

As someone who has endured a sometimes troubled relationship to his own creativity,1 and who has found a rich vein of gold in exploring the personification of creativity in the concept (and the vivid experience) of an accompanying muse/daemon/genius, I find the Frankenstein story to be extraordinarily insightful, and also disturbingly cautionary, not only and not even primarily in the ways that have been called out by the legions of readers and commentators who have analyzed it ad nauseam as a tale of scientific hubris and the Promethean dangers of “playing God.” To me, Frankenstein, which Brian Aldiss once astutely characterized as “the first great myth of the industrial age,”2 approaches the status of a master archetype whose meanings can be mined for deep psychological and spiritual application.

. . . a heady cognitive-emotional state of intensified synchronistic sensitivity that is typical of encounters with the numinous guidance that lies behind and beneath the veil of the individual ego mind.

So, when the title for the unexpected poetic lines above unexpectedly suggested itself, and when I tracked down its origin and found myself (re)reading that resonant passage from late in the story of Victor Frankenstein’s descent into a daemonically driven visionary hell, this was simultaneously surprising, confirming, and unsettling. In other words, it evoked a heady cognitive-emotional state of intensified synchronistic sensitivity, which, as I have learned and relearned over the years, is typical of encounters with the numinous guidance that lies behind and beneath the veil of the individual ego mind.

As for what those lines might mean, I can only say that they’re quite meaningful to me as a helpful tool for spiritual course correction, and that I take no credit for having written them.

Disclosure: I’m an affiliate of Bookshop.org, which helps local, independent bookstores thrive in the age of ecommerce. I’ll earn a commission if you click through one of the book links in this post and make a purchase.

On this topic, see my essay “Initiation by Nightmare: Cosmic Horror and Chapel Perilous.”

Brian W. Aldiss, Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction (Garden City: Doubleday, 1973), 23.

“People who deny the existence of dragons are often eaten by dragons. From within.”

-Ursula K. LeGuin

Lovely poem. Intriguing discussion.