Two Visions of Writing in the Age of AI

Ego, effort, and the machine

This blog/newsletter is free, but if you feel drawn to support it materially, see the options at the bottom of this post.

If this was forwarded to you and you like what you read—or if you’re generally interested in writing, creativity, cultural questions over AI, and the numinous undercurrents that flow beneath these things and more—consider subscribing.

Dear Living Dark readers,

I know many of you are writers. And also artists, musicians, and various other species belonging to the socio-spiritual genus that we sometimes call “creator.” Regardless of where or even whether you fall in that group, it’s clear we’re all interested in the question of creativity, including what it is, what it means, how it works, where it comes from, and how it relates to the rest of our lives. Otherwise, why would you be reading a post like this in a publication like The Living Dark? We’re also probably all interested in the subject of artificial intelligence, since, well, who isn’t these days? And since, as you may recall, I have already written about it several times in the past, effectively chronicling my own evolving understanding of it.

This is all why I figured you might find the following two perspectives, and the contrast and tension between them, to be as interesting and provocative as I do. Each lays out in miniature a complete weltanschauung of the relationship between writers, their work, and artificial intelligence. Each does a fine job of making its case. And each fundamentally disagrees with the other, almost on a point-for-point basis. This means it’s worthwhile to reflect, even to meditate, not only on each separately but on the dialectical tension between them.

The first perspective, which I’ll label View A, comes from a recently published piece by Nick Ripatrazone, the culture-oriented author and editor whose interesting and subtle views on religion, literature, and other topics I have found consistently engaging for years.

VIEW A:

Artistic ego is the best chance we have of battling against the rise of AI in creative spaces. When we write something and decide to share it with others, we are affirming the worth of our own words, which is an action of the ego. . . . Great art isn’t supposed to be easy. While it’s easy to fetishize the trope of the struggling artist, art results from failure overcome by determination. The artistic ego, in asserting itself, is a human action. When we cede creation to the machine, we are not making art. Reddit posts abound in which people turn to AI to ease their writer’s block, as if it is a temporary inconvenience. The struggle, in fact, feeds the art.

— Nick Ripatrazone, “Against Generative AI: Is Art the Last Refuge of Our Humanity?” Literary Hub, January 15, 2026

The second perspective, which I’ll label View B, comes from the book The Art of Unwriting by Youri Hermes, which hasn’t been published yet, and for which I will be writing the introduction.

VIEW B:

The identity that manages, controls, and worries about being good enough. The voice that asks “Am I qualified to say this?” and “Will anyone care?” The self that turns writing into performance. When the writer falls away, so do the problems it creates. Writer’s block, perfectionism, procrastination. These only exist when we believe we’re the one who has to write the book. When there’s no writer, what’s left to be blocked? No writer, no problem. Remove the writer, and the obstacles dissolve with it. . . . We stop carrying the entire burden of making our writing clear. We see that clarity often emerges through the relationship between our words and other minds, both human and artificial. . . . The effort, the struggle, the inspiration, it was never really yours. AI just makes that obvious. It reflects back what’s always been happening: creativity appearing from nowhere. With or without you.

— Youri Hermes, The Art of Unwriting: Freeing the Book from the One Who Writes It (forthcoming)

Since I’m the one who has brought this all up, it probably behooves me to state where I myself stand on these dual outlooks. So here goes:

The plain fact is that I can’t champion either view exclusively and remain honest, as aspects of both describe my personal experience, deeply known and intensely engaged over decades.

The recognition-in-action that the pause and suffering of creative block can actually be the thing that infuses writing with the quality and soul it needs? Check.

The contrasting recognition that creativity is literally always happening, that my writing isn’t actually, ultimately mine, that it doesn’t belong to me, that it appears from nowhere, and that therefore struggling with block can represent self-deception and even a kind of needless sidetrack? Check.

Profound misgivings about AI’s ability to short-circuit the slowness, effort, and suffering of that soul-productive block, combined with a growing fascination with the way the instantaneous muse-like flow of words (or other things) from generative AI seems like a concrete illustration of potential creative meaning being profligately produced from essentially nowhere, just like whispers from the daemon muse itself? Check.

A sense of being poised in a kind of fertile liminality as I contemplate this tension and watch for the synthesis that might eventually emanate from it? Check.

And now: How about you? Is creative struggle essential, or is it an illusion we’ve mistaken for virtue? And how does artificial intelligence play into it, if at all?

Warm regards,

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with a friend. I’d also love to hear your thoughts and comments.

Support This Work

If you want to materially support The Living Dark, you can make a one-time donation or choose a recurring monthly donation. I spend a lot of time tending this project, so I sincerely thank you for even considering it. All posts will always remain free.

One-time donation:

Recurring donation:

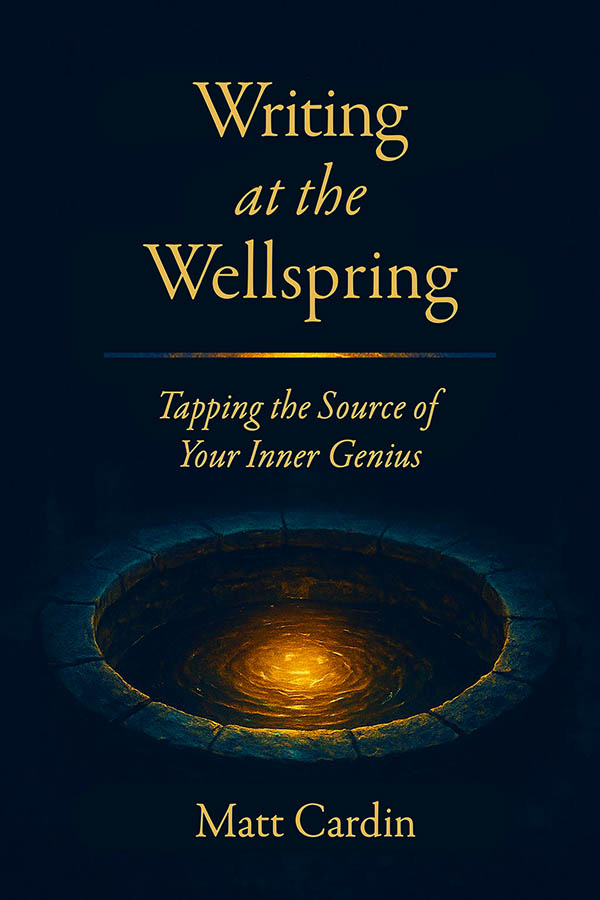

Published in December:

“[An] intimate journey into the mystery of creativity and spirit… Cardin weaves practical methods, personal stories, literary references, and mystical insights into a lyrical meditation on what it means to create from the depths of the soul… both deeply personal and universally resonant.”

— BookLife review (Publishers Weekly)“A guide for writers who welcome the dark and hunger for meaning.

— Joanna Penn, author of Writing the Shadow“I can’t think of any [other books] that link the creative act so uniquely or persuasively with spirituality.”

— Victoria Nelson, author of On Writer’s Block and The Secret Life of Puppets“A meditation on the silence and darkness out of which all creative acts emerge....A guide for writers unlike any other.”

— J. F. Martel, author of Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice and co-host of Weird Studies“Important to any writer ready to see through the self illusion and realize the freedom this brings to any creative work.”

— Katrijn van Oudheusden, author of Seeing No Self

Available from all the major stores, including Amazon, Bookshop.org, and Barnes & Noble.

I drafted a reply and it got mangled and eaten. Then kicked me off your substack and tried to make me sign in...weird. Trying again!

I don't think struggle is necessary to art, but I do think work or process is. When I was a writer, my experience was that I didn't make things up, but rather that stories came through me, physically. My role was to attune my physical presence in order to become open to the story. I had to make myself into a channel or medium and bring the stories to the page. The process of writing is a shamanistic one, in other words.

I think this is even more so with visual art, which is more physical than writing. (Although I also always contended that writing is a physical endeavour.)

If AI can produce a work that has artistic value, that value inheres in its consumption only. For an artist, the value of an artwork is in its making. That is where we learn, transform, experience it fully, experience ourselves in its creation, and experience ourselves as creators and as divine.

So maybe AI can produce art that has value to the viewer or reader. It may produce art that has value to the individual prompting the AI. But it cannot produce art that has value to the artist as an artist, because for the artist, it is the work (process, sometimes struggle) itself that is of value.

“But what we did not render obsolete was the fear humans have of other minds. This society—what we call modern society, what we always think of as the most important time the world has ever known, simply because we are in it—is just the sausage made by grinding up history. Humanity is still afraid the minds we make to do our dirty work for us—our killing, our tearing of minerals from the earth, our raking of the seas for more protein, our smelting of more metal, the collection of our trash, and the fighting of our wars—will rise up against us and take over. That is, humanity calls it fear. But it isn’t fear. It’s guilt.”

“Guilt?”

“Yes, guilt. It’s a revenge fantasy. We are so ashamed of what we have done as a species that we have made up a monster to destroy ourselves with. We aren’t afraid it will happen: We hope it will. We long for it. Someone needs to make us pay the price for what we have done. Someone needs to take this planet away from us before we destroy it once and for all. And if the robots don’t rise up, if our creations don’t come to life and take the power we have used so badly for so long away from us, who will? What we fear isn’t that AI will destroy us—we fear it won’t. We fear we will continue to degrade life on this planet until we destroy ourselves. And we will have no one to blame for what we have done but ourselves. So we invent this nonsense about conscious AI.”

-Ray Nayler, "The Mountain in the Sea"